The stretch of London Road now numbered as 145–151 lies on the west side, between Montague Road and Chatfield Road, and is currently used for two very distinct types of activity. The upper floors of the building on the south side of the site are occupied primarily by Christian churches and community groups, while the ground floor and the open space on the north side of the site are home to car-related businesses.

Given the size of this site, with a frontage of 67 metres on London Road,[1] it should be unsurprising that its initial development included more than one property — in fact, there were once four houses along this stretch. I’ll therefore be covering it in four articles, one for each house going from south to north. In this first article, I’ll also describe the initial development of the land, and in the final article, I’ll include a discussion of the present-day occupants.

1820s–1830s: Extinguishment of common rights, and the sale of the land

Along with everything else on the west side of London Road between Derby Road and Chatfield Road, the site was originally part of an area of common land known as Parson’s Mead. Most of Croydon’s common land was enclosed — that is, fully privatised, with all common rights removed — in 1801. However, Parson’s Mead was explicitly excluded from the parliamentary act which permitted the main enclosure, and hence remained common land until the 1820s.[2]

At first glance, the term “common land” might seem to imply some sort of communal ownership — or even no ownership at all. However, in the context of English law it actually refers to privately-owned land over which certain other parties have certain rights; for example, the right to graze animals such as cows and horses. Writing in 1882, Croydon historian John Corbet Anderson[3] described the exercising of this right over Parson’s Mead:

“Fifty years ago it was customary after hay-harvest — viz., on Lammas-day — for those who enjoyed the right, to turn out one or two head of cattle into this meadow.”

The Parson’s Mead Enclosure Act was passed in 1823, and Martin Nockolds was appointed as commissioner for dividing up the land and deciding on compensation for those whose common rights were being extinguished. Although the freeholds of a few small plots of land were allotted as compensation, the vast majority of Parson’s Mead remained in the hands of the existing freeholder.[4]

This freeholder was not an individual, but the trustees under the will of Alexander Caldcleugh, who until his death on 18 January 1809 had been “seised of or otherwise well entitled to a certain Piece or Parcel of Meadow Land called Parsons Mead, situate within the Manor of the Rectory of Croydon otherwise Bermondsey, in the Parish of Croydon in the said County of Surrey, subject to certain Rights of Common upon or over the same”. With the removal of these rights of common, the trustees were now free to do whatever they liked with the land, within the constraints of the will.[5]

Alexander had lived at Broad Green House, just beyond the north end of Parson’s Mead, and his widow Elizabeth continued to live there after his death. However, after Elizabeth herself died, on 8 February 1835, both Broad Green House and the Parson’s Mead land were auctioned off. The latter was split up into small lots for the auctions, and the plots fronting on London Road ended up being owned by a total of eleven different people.[6]

1840s–1850s: Houses are built on the south side of the site

The area between the modern Montague Road and Chatfield Road was at the north end of Parson’s Mead, just south of Broad Green House itself. The north side of the site was bought by Jonathan Barrett, while the south side of the site, which is now occupied by Praise House, was bought by Henry Overton.[8] The 1844 Tithe Award map records Henry Overton’s plot simply as a meadow, but by 1849 at least two houses had been built. A third house was built either at the same time or very shortly afterwards.[9]

1850s: William Ashmead Tate

By 1852, this third house — the southernmost of the three — was occupied by William Ashmead Tate and his wife Isabella. William was a professor at Addiscombe College, a military seminary run by the East India Company. Although born in Bombay, he himself attended Addiscombe College from the age of 15 before returning to India in 1813, aged just 17, to work as a surveyor and draughtsman under the Revenue Surveyor of Bombay.

William’s job appears to have involved a great deal of outdoor work, and by late 1827 his health had suffered to the point where he was forced to return to England before retiring from the service a couple of years later on a pension of 7 shillings a day (£12,650/year in 2015 prices).

In 1849, he was appointed professor of military drawing at Addiscombe College at a salary of £400/year (£45,843 in 2015 prices), where he taught for the next decade before retiring to Weston-super-Mare. In his history of Addiscombe College, H M Vibart states that William “was as kind-hearted as he was clever, and was much liked and respected by the cadets.”[11]

1850s–1860s: Joseph Parrinton; John Walkden

By late 1858, William and Isabella had departed London Road and been replaced by Joseph Parrinton.[13] Joseph moved his family here from 35 Thornton Heath, a “mansion” further up London Road, after the suicide of his oldest son, Walter. Walter’s death took place in the family home, and it seems quite possible that the Parrintons simply felt unable to continue living there afterwards.[14] They only remained briefly in their new home, however, and by late 1860 had in turn been replaced by John Walkden.[15]

1860s–1880s: The Goodinges and the Finns

By 1865, John himself had departed and the premises were occupied by two households: one consisting of 60-something stationer James Boote Goodinge along with his wife Mary Oliver Goodinge and son William, and the other consisting of James and Mary’s daughter, Mary Ann, and her husband Charles Francis Finn, a commercial traveller in his late 20s. It isn’t clear how the house was subdivided; street directories place the two families at the same address, but the 1871 and 1881 censuses consider them to be in separate households.[16]

Charles died at home on 6 December 1888 “after a long and painful illness”,[17] following which his wife and her parents moved to a smaller house further up the road, just south of the junction with Sumner Road.[18]

1890s–1900s: Thomas Arthur Richardson; Robert Charles Brown

The Goodinges and Finns were replaced by Thomas Arthur Richardson, a surgeon who had previously lived at number 61 and number 67–71. Thomas was here from around 1890 until around 1903, when he moved to Combe Martin in Devon. His replacement was another surgeon, Robert Charles Brown. Robert, however, only remained a handful of years; by 1908, he had moved just up the road to a semi-detached house which was formed in the early 1890s by splitting Broad Green House into two properties.[19]

1900s–1910s: Henry and Lydia (and Lydia) Goulder

The next occupants, Henry and Lydia Goulder, appear to have been of more modest means than their predecessors. Henry was a joiner, and their adult daughter (also named Lydia) was a pianist at the Electric Theatre on North End, but the family supplemented their income by taking in lodgers — five of them, at the time of the 1911 census. They arrived on London Road by 1909, giving their new home the name of Wroxham House, but had departed again by 1913.[20]

1910s: The YWCA Institute and Hostel

Use of the premises to provide lodgings continued in a somewhat different form after the Goulders’ departure, as the next occupant was an “Institute and Hostel” run by the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

This organisation had its roots in two projects, both initiated in 1855. The first was a prayer union in Barnet, founded by Emma Robarts and named the Young Women’s Christian Association after the example of the existing Young Men’s Christian Association. The second was a network of hostels for young women living away from home, which expanded from a nurses’ home founded in Upper Charlotte Street, central London, by Mary Jane Kinnaird. When the two strands of the organisation merged in 1877 there were several hostels in London as well as in other towns including Bristol, Birmingham, Liverpool, and Manchester.[21]

The YWCA had a presence in Croydon by 1882, in the form of a “Home and Institute” on Park Lane.[22] From here it moved to George Street around 1885, to the High Street around 1897, to Poplar Walk around 1908, and to London Road around 1913.[23]

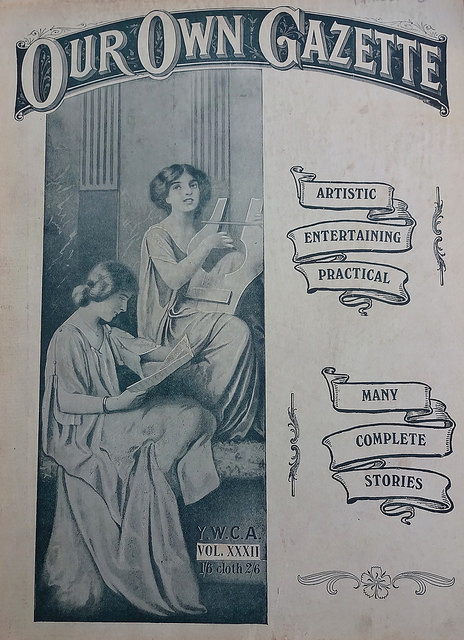

By the time of its arrival on London Road, the YWCA had branches in over 20 different countries, all united under the banner of the World YWCA.[24] Our Own Gazette, the UK organisation’s official monthly magazine, had a circulation of over 40,000 and included articles on subjects such as the life of Florence Nightingale, the reasons behind the outbreak of the First World War, and details of how wounded soldiers were brought home from the front, as well as less war-oriented subjects such as instructions for setting up a sickroom to nurse a family member at home, ways to test the freshness of an egg, and an illustrated essay on the old wind and water mills of the English countryside.[25]

Continuing its pattern of moving around Croydon, however, the organisation remained on London Road for only a handful of years. By the end of the decade it had relocated again, this time for another stint on George Street.[26]

1920s: Miss Earl and Mlle Neveux

Next to arrive were Miss Earl and Mlle Neveux. Little information survives about the former, but the latter was a teacher of French. They remained on London Road until the end of the 1920s.[27] It’s not clear where they went after that, but Mlle Neveaux at least seems to have remained in the area, and by 1939 was providing her French lessons on Friends Road.[28]

1930s–1960s: Smith Auto Co

The departure of Miss Earl and Mlle Neveux saw the end of the residential use of the property. This was also likely the point at which it was completely redeveloped, with not only an extension forwards to the pavement line but also new buildings at the back, running along Montague Road.[29]

The new occupant was Smith Auto Co, a car dealership specialising in the sale and servicing of Humber, Hillman, and Sunbeam cars. In place by 1930, it remained until the mid-to-late 1960s.[30]

Late 1960s: Demolition

Smith Auto Co, as it turned out, was the final occupant of this property, as its departure signalled the redevelopment of the entire site between Montague Road and Chatfield Road. The land divided between Henry Overton and Jonathan Barrett over a century before was finally reunited — and so the full story of this will be told in a future article.

Thanks to: David Jones of Bygone Croydon; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-reader Alice. Census data consulted via Ancestry.co.uk.

Footnotes and references

- Distance measured using Google Earth from the northwest edge of Montague Road to the southeast edge of Chatfield Road.

- Full details of the main Croydon enclosure can be found in John Corbet Anderson’s book Plan and Award of the Commissioners Appointed to Inclose the Commons of Croydon (1889).

- John Corbet Anderson, A Short Chronicle Concerning the Parish of Croydon (1882), p. 192. There is clearly some rounding of dates here, since “Fifty years ago” technically refers to 1832, whereas common rights were removed from Parson’s Mead in the mid-1820s.

- Full details of Martin Nockolds’ decision can be found at the Parson’s Mead enclosure section of this website.

- The constraints of the will were of some importance here, since Alexander had stipulated that his trustees were only allowed to lease out his freehold land “for any term not exceeding Fourteen years”. Leases this short were not attractive to speculative builders, and land this close to central Croydon was ripe for development. Shortly after the enclosure of Parson’s Mead, a new act of Parliament was passed to allow longer leases to be granted: “An Act to enable the Trustees under the Will of Alexander Caldcleugh Esquire, deceased, to grant Building Leases of Lands in the Parish of Croydon in the County of Surrey” (6 Geo IV cap -30; Parliamentary -Archives ref HL/PO/PB/1/1825/6G4n298). The quotation regarding Alexander’s entitlement to Parson’s Mead is taken from this act. For full details of Alexander’s will, see my transcription of the probate register copy.

- For more information on the division of the Parson’s Mead land, see my article on 21 London Road, part 1. I discuss the Caldcleughs at greater length in my article on Broad Green House. Pages 33–35 of Urban Development and Redevelopment in Croydon 1835–1940 (Ron Cox, PhD thesis, Leicester, 1970) are also relevant. Elizabeth’s death on 8 February 1835 is mentioned in a notice in the 11 February 1835 Morning Post (page 4, column 5) viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription), which describes her as “relict of the late Alexander Caldcleugh, Esq.”.

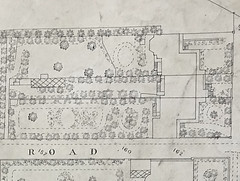

- 1835 map reproduced courtesy of Stiles Harold Williams and the Museum of Croydon (loose sales particulars ref BA268). Modern roads overlaid using Toner Lite map tiles by Stamen Design, under Creative Commons cc-by (retrieved 24 June 2013).

It took at least two auctions to dispose of all the Parson’s Mead land with a London Road frontage; one on 23 May 1835 and another on 21 April 1838. Henry Overton’s purchase for £385 (£38,500 in 2015 prices) of a piece of land with a frontage of 121 feet (37 metres) is recorded as a handwritten notation on the copy of the sales particulars for the 21 April 1838 auction bound in the Harold Williams volumes at the Museum of Croydon (Volume 1837–1840, Section CXVI). This 37 metres is pretty much exactly the distance from the middle of Montague Road to the north edge of Praise House as measured using Google Earth.

Henry was a brewer as well as a landowner; Overton’s Brewery, based on Surrey Street, later became Page & Overton’s, which survived into the 20th century. For evidence that this was the same Henry Overton, see the Museum of Croydon’s Marshall Liddle & Downey index summary of a deed dated 9 February 1847 (index page 19), which states that “Henry Overton of Croydon brewer” owns “whole of north side of [Montague] road”. I discuss Henry — and his descendants — at greater length in my article on number 149.

- The July 1849 Lighting Rate Book lists “S Jackson” and “Moss” on this part of London Road. Rate books generally omitted unoccupied dwellings, so the third house may well have been in existence then too, and indeed the shapes and position of the houses on later maps strongly suggest that they were built together as a block. Gray’s 1851 directory lists one house “To Let” and two others occupied by Samuel Jackson and Charles Moss. The 1868 Town Plans make it clear that all three houses were to the south of Kidderminster Road (a side road opposite), and hence on the land bought by Henry Overton.

Note that these two purchases took place in 1838, not 1835, and so the corresponding names must have been written onto the map some time after it was first produced. In the original, which is in colour, they are in fact in a different colour of ink — red, as opposed to the black of the other names — as is the line drawn through the middles of lots 3 and 48. (The version reproduced here is a scan of a black-and-white photocopy.)

Note also that although the land was offered in six lots (2, 3, 4, 47, 48, and 49) in 1835, it was consolidated into two for the 1838 sale, with lots 3 and 48 being split down the middle. (For proof of this, see the sales plan included in Harold Williams Volume 1837–1840, Section CXVI, at the Museum of Croydon).

- The Museum of Croydon’s Marshall Liddle & Downey index summary of a deed dated 1 March 1858 (index page 49) states that Captain William Ashmead Tate had leased this property for 21¼ years from Christmas 1851. Gray’s 1853 and Gray & Warren’s 1855 directories list Captain William Ashmead Tate, E.I.C. [East India Company], Professor at Addiscombe College. The 1851 and 1861 censuses list Isabella as William’s wife (on Addiscombe Road and in Weston-super-Mare respectively); the former of these also lists a 16-year-old daughter while the latter lists a 7-year-old son, but it isn’t clear whether either of these lived in the London Road household. Quotation and all other information taken from pages 212–216 of Addiscombe, Its Heroes and Men of Note by H M Vibart.

- The photo is labelled simply “East Front” in the list of illustrations. Page 14 states that the east front was the “public entrance” to the seminary. This image has also been collected at Wikimedia Commons; its description there states that it was taken c.1859, but there’s no indication of where this date comes from.

- Jos [Joseph] Parrinton is listed in William’s place in the October 1858 Poor Rate Book and Gray & Warren’s 1859 directory. William continued to work at Addiscombe College until 1859, so he and Isabella presumably spent a short while living elsewhere in Croydon before finally moving to Weston-super-Mare.

- Information on Walter Parrinton’s death is taken from a front-page report in the 25 August 1856 Evening Standard (bottom of third column; viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription.) Their address at the time is taken from Gray & Warren’s 1855 directory.

- John Walkden is listed in the November 1860 Poor Rate Book and Gray & Warren’s 1861–62 directory.

- The Goodinge family may have arrived slightly before the Finns, or they may have moved in at the same time. James Goodenge [sic] is listed in Simpson’s 1864 directory and Poor Rate Books from December 1865 onwards. Directories from Warren’s 1865–66 onwards list both James and Charles. Information about their professions, ages, and families is taken from the 1871 census, and their full middle names are taken from Kelly’s 1889 directory. Relationship between Mary Ann and James/Mary Oliver is confirmed by the record of Mary Ann’s marriage to Charles at the Parish Church of St Botolph, Aldersgate, on 14 August 1860. Mary Oliver Goodinge’s full middle name is taken from her witness signature on said marriage record, and confirmed by her entry in the National Probate Calendar.

- Information about Charles’ death, including quotation, taken from his death notice on the front page of the 8 December 1888 Morning Post, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription). This specifies that he died at 46 London Road (later renumbered to 87 and then 145).

Ward’s directories list James Goodinge and Charles Finn at 46 London Road up to and including 1889; James Goodinge and Mrs Finn at 117 London Road (later renumbered to 197) in 1890; Mrs Goodinge and Mrs Finn at 117 London Road in 1891; Mrs Finn alone at 117 London Road from 1892 to 1900 respectively; and Mrs Finn on Chatfield Road from 1901 onwards. Note that the data for these directories was generally finalised late the previous year. Comparing entries in Ward’s directories with contemporary maps, 117 London Road was the third house south of Sumner Road, in a location now occupied by Gary Court.

Measuring on the 1868 Town Plans, the footprint of the Goodinges’ and Finns’ old house is 105m² while the footprint of their new house is 70m². It is of course possible that the new house had more storeys than the old one. However, the old house had room for at least five lodgers as well as a servant and a family of three adults (see in the main text under “1890s–1910s”), while censuses from 1851 to 1891 show six resident adults at most in the new one (four, five, six, three, and four in 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, and 1891 respectively, with similar numbers in the other half of this semi-detached pair: five, four, five, three, and three respectively; both houses are vacant in the 1901 and 1911 censuses).

James died a year after the move, on 20 December 1889, and Mary Oliver followed him on 31 October 1891, but Mary Ann continued to live on London Road until around 1900, when she moved to 7 Chatfield Road, just around the corner from where she’d lived with Charles. She died there on 15 April 1910. (Note that Chatfield Road wasn’t built until the early 1890s, after James and the two Marys had already moved up towards Sumner Road.)

Dates and places of James’ and Mary Oliver’s deaths are taken from his entry and her entry, respectively, in the National Probate Calendar, both of which give the address of 117 London Road. James also has a death notice on page 11 of the 29 December 1889 Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription). Mary Ann’s date and place of death taken from her entry in the National Probate Calendar, which gives the address of 7 Chatfield Road.

- Ward’s directories list Thomas at this property from 1891 to 1903 inclusive, and Robert Chas [Charles] Brown, physician and surgeon, from 1904 to 1907 inclusive. From 1908 to to 1924 inclusive, they list Robert at number 103a, which was previously known as Chatfield House; a comparison of the 1868 and 1896 Town Plans makes it clear that Chatfield House was formed from the northern half of Broad Green House, and the former first appears in Ward’s directories in the 1893 edition. See my article on 61 London Road for more information on Thomas, and I’ll discuss Robert further in my article on Chatfield House.

- Henry Arthur Goulder, Wroxham House, is listed in Ward’s directories from 1909 to 1912 inclusive. The name of the house may have been chosen by Lydia senior; the 1911 census shows that she was born in Stokesby, Norfolk, and there’s a town in Norfolk called Wroxham relatively near Stokesby. Information on employment and lodgers is taken from the 1911 census. The Electric Cinema was at 108 North End (in modern numbering), with the entrance where Northend News is today; more information can be found on the Cinema Treasures website. According to the latter source, the cinema had actually closed down for redecoration the day before the census was taken, and remained closed for two years. Presumably either Lydia junior thought it would reopen sooner, or she was unwilling to put herself down as being of no occupation. (The closure was on 1 April 1911; the census was on the night of 2/3 April 1911.)

- Information taken from an archive note on the YWCA page at Warwick University Modern Records Centre, and Our Eighty Years: Historical Sketches of the Y.W.C.A. of Great Britain (published 1935), page 20. More information on Mary Jane Kinnaird can be found in her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (requires login; a Croydon Libraries library card number will do).

- Ward’s directories list a YWCA “Home and Institute” at 2 Park Terrace, Park Lane in 1882, 1884, and 1885. It’s not there in 1880, and I can’t find it in the alphabetical list either.

Ward’s directories list a YWCA branch at 83 George Street from 1886 to 1888 inclusive; 48 George Street from 1889 to 1894 inclusive; 64 George Street in 1895; and 56 George Street in 1896 and 1897. Comparison of other directory entries shows that the change in address from 1888 to 1889 was just a street renumbering, but that the others were actual moves (there was another renumbering of part of George Street between the 1894 and 1895 editions, but not affecting the YWCA). The placement of the YWCA entries at the latter two locations suggests that it may have been located on an upper floor or perhaps a back room, as it’s alongside another business at the same address. In 1893 and 1894 a resident superintendant is also listed.

These directories then list a YWCA “Boarding House & Institute” (or “Institute and Hostel” from 1914) at 36a High Street from 1898 to 1904 inclusive; at 2 Leamington Villas, Poplar Walk, from 1905 to 1908 inclusive; at 1–2 Poplar Walk from 1909 to 1911 inclusive; at 2 Poplar Walk in 1912 and 1913; and at 87 London Road (later renumbered to 145) from 1914 to 1919 inclusive.

- YWCA archive note, Warwick University Modern Records Centre.

- Circulation numbers and examples of articles in Our Own Gazette taken from various issues in volume 32 of the magazine (Nov 1914-Oct 1915), viewed at the British Library.

Ward’s directories list a “Y.W.C.A. Institute and Hostel” with a “Lady Superintendant” (initially Miss Harris, and then Mrs Dear) at 87 London Road (later renumbered to 145) from 1914 to 1919 inclusive. They then list a “Y.W.C.A. Blue Triangle Club” at 71–73 George Street in 1921 and 1922 and 71 George Street from 1923 to 1926 inclusive; and a “Y.W.C.A. Hostel and Club” at 8 Sydenham Road from 1927 to 1930 inclusive and 8–10 Sydenham Road from 1932 to 1939 inclusive (1939 being the final edition of these directories).

Regarding the Blue Triangle Club, Our Eighty Years states on page 6 that “During the war [i.e. the First World War] the Association became known to a wider public as under the Blue Triangle, corresponding with the Red Triangle of the Y.M.C.A. Gradually the Blue Triangle with bar and initials was adopted as the general membership badge.”

- Ward’s directories list Miss Earl and Mlle Neveux, “Teacher of French”, from 1920 to 1928 inclusive, Miss Earl alone in 1929, and Smith Auto Co Ltd from 1930 onwards.

- Neither Miss Earl nor Mlle Neveaux appear in the alphabetical lists of residents or tradespeople in Ward’s directories after leaving London Road, but an advert on page 17 of the 10 March 1939 Croydon Advertiser (reproduced here) places the latter at 6 Friends Road. According to Ward’s directories, during the 1930s, 6 Friends Road was occupied by a succession of women, none of them named Neveaux: Mrs W M Sanders, Mrs E A Sandbach, and finally Miss Prideaux. It seems possible that Mlle Neveaux was lodging with one or all of them.

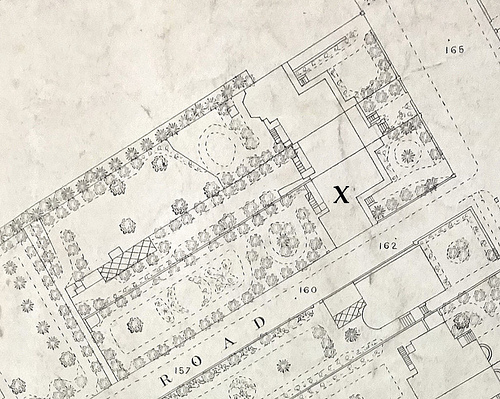

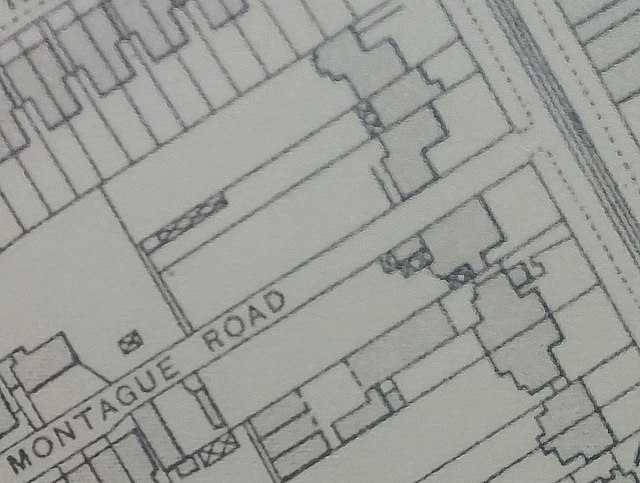

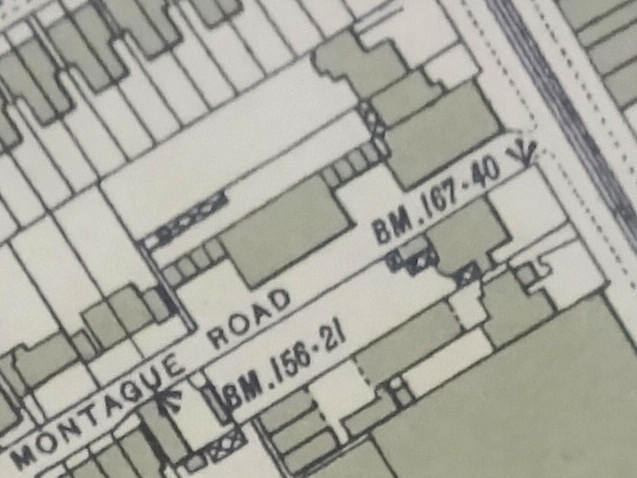

- As shown by the map extracts reproduced here, the 1932 Ordnance Survey map has a forwards extension of number 145 to London Road and several buildings along the north side of Montague Road, none of which is evident in the 1913 edition. (Unfortunately neither the Museum of Croydon nor the British Library have any Ordnance Survey maps between these dates.) At least some of the Montague Road buildings were in place before Miss Smith and Mlle Neveux departed; those just north of the “GUE” in “MONTAGUE ROAD” first appear as “Houses building” in Ward’s 1925 directory and as numbers 4 and 6 Montague Road from 1926 onwards. The buildings to the northeast of these, at the back of number 145, seem not to appear in Ward’s directories at all. However, it seems unlikely that the building work required for extension would have taken place while Miss Smith and Mlle Neveux were still living there.

- Smith Auto Co is listed at 145 London Road in Ward’s directories from 1930 to 1939 inclusive (after which no more of these directories were published). It also appears in Kent’s 1955 and 1956 directories, and phone books up to and including the August 1967 Croydon edition. As further evidence, the firms files at the Museum of Croydon include an invoice from Smith Auto Co, 145 London Road, dated 8 October 1963. A planning application submitted on 6 March 1968 (viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices; ref 68/20/433/D) states that as of that date the property had been a “Garage and workshop until vacated recently”. Moreover, Dave Harwood notes that a London Metropolitan Archives photo from 1968 has posters in the windows which look like flypostering, again indicating that Smith Auto Co had closed down by that time. Information on the company’s specialisation in Humber, Hillman, and Sunbeam cars is taken from the advert reproduced here. The abovementioned 1963 invoice also includes these names in its heading.