The weary traveller who exits West Croydon Station in search of sustenance on London Road need look no further than the Ship of Fools. Almost directly opposite the station, this Wetherspoon’s pub is large and welcoming, with friendly staff, interesting real ales, and well-priced food.

Sadly, the pub is due to close at some point during 2013, as Wetherspoon’s have sold the lease of the premises to Sainsbury’s. Those with a keen eye on Croydon’s local media will already know that this marks a return to 9–11 London Road for Sainsbury’s, which was probably the most prominent — and certainly the most long-standing — previous occupant of the premises.

London Road in the early 1800s

As noted in a previous article, numbers 7–11 London Road were constructed later than their neighbours, filling in a gap between number 5 to the south and number 13 to the north[2]. This piecemeal construction is fairly typical of London Road, but it occurs to me that I haven’t yet explained the reason why; so here is a brief diversion to elucidate.

Until around 1824, the area between the top end of North End and the present location of Chatfield Road was occupied by a piece of common land known as Parson’s Mead[3]. The Parson’s Mead Enclosure Act was passed in 1823, and most of the land then came into the possession of the Caldcleugh family, who already owned land further north at Broad Green[4]. However, it remained undeveloped for some years afterwards.

In May 1835, the Caldcleughs offered for auction the land bounded by present-day Sumner Road, Handcroft Road, Parson’s Mead, and London Road. The six acres at the north end of this, consisting of Broad Green House and its grounds, were purchased by Jonathan Barrett of Streatham. The rest of it, running along the west side of London Road, was divided up into 62 separate lots. All known purchasers of these smaller pieces of land were Croydon residents, and none bought more than a few lots, so the land ended up being owned by multiple people, each with a small piece. Hence, development proceeded in a fairly patchwork fashion, as is obvious from the varying architectural styles still visible today[5].

1870s–1880s: Construction of the building, and John James Sainsbury’s model shop

Numbers 7–11 London Road were built between 1877 and 1880. In contrast to the current situation, with numbers 9 and 11 knocked into one, they were originally all separate premises. However, they were all owned by the same person — John Sainsbury, provision dealer[6]. After purchasing the properties in the early 1880s, Sainsbury leased numbers 7 and 9 to other businesses[7] and set about outfitting number 11 as a new style of grocery shop.

Although John Sainsbury had opened seven other shops before this one[8], the London Road branch was a turning point in the growth of his grocery empire. It was aimed firmly at the middle classes[9], and the focus was not only on elaborate decor but perhaps more importantly on cleanliness, which was not a particular strength of the retail food trade at the time[10].

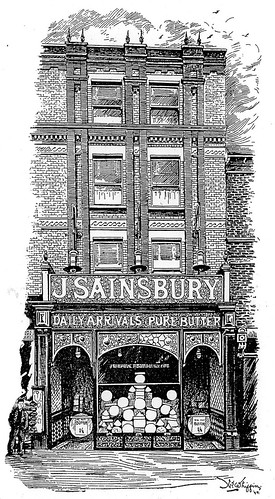

The Story of Sainsbury’s (published by J Sainsbury Limited, April 1969) describes the shop thus: “The windows were framed by marble-faced pillars, wood, and stained glass spandrels; the fascia, was crowned with wrought iron and displayed the Sainsbury name in gilded glass. The floor was tiled, as were the walls and counter fronts, in the lush designs of the period and the counter tops were made of marble slabs. The office was built of polished teak, the customer's side of the counter furnished with bentwood chairs.” It opened in 1882[11], and in the mid-1890s was expanded into number 9 next door[12].

Sainsbury’s Croydon store was to be only the first of many other stores in the same style. In 1888, similar branches were opened in Balham, Brondesbury, and Lewisham, all modelled on the store at 11 London Road[13]. The West Croydon branch thus acted as a template for Sainsbury’s move towards catering for a wealthier class of customer.

1950s: Sainsbury’s first self-service store

This was not the only way in which the store was important in Sainsbury’s history. It should be remembered that when John Sainsbury began to build his empire, grocery shopping was very different from the way it is today. Instead of picking up prepackaged food from a shelf, shoppers would queue up in different shops — and even at different counters within the same shop — for their goods to be weighed out and individually wrapped. This somewhat inefficient way of buying goods remained standard in the UK until the middle of the 20th century[14].

In 1949, however, Alan Sainsbury and fellow director Fred Salisbury went to the USA to learn more about the deep-frozen food industry and instead became fascinated by the idea of self-service retail. Keen to try this idea for their own stores, they conducted an experiment — a sort of pilot study — with the branch at 9–11 London Road. As this branch occupied a double shopfront, its size made it the ideal place to try this, as half of it could be closed at a time, allowing trading to continue during conversion works[15].

Sainsbury’s first self-service store opened on London Road on Monday 26 June 1950[16]. An article published in the Croydon Advertiser later that week describes the new system as an “American-inspired ‘Help yourself’ scheme”, and provides a detailed explanation of the process of self-service shopping: “On entering the shop the housewife is given a wire basket or, if she intends to make a very large number of purchases, a two-tier wire trolley. She is then free to wander at will round the stainless steel and perspex stands which are closely packed with every type of grocery imaginable and clearly labelled. Every commodity has a price ticket and when the housewife has completed her tour she checks out at one of five exits, empties the wire basket and pays her bill.”[17]

1970: A decimalisation training centre

Another chapter in Sainsbury’s history also began at this branch — decimalisation. Following an announcement by the Chancellor of the Exchequer on 1 March 1966, the UK was set to convert its currency from pounds, shillings, and pence to decimal pounds and pence on 15 February 1971[18]. In order to train its staff and acclimatise its customers, Sainsbury’s set up a “training shop” at 9–11 London Road. From 10 February to 27 November 1970, over 1,500 key staff from different branches were trained to use the forthcoming currency, selling goods with plastic coins to over 30,000 visitors including specially-invited groups such as Townswomen's Guilds and Women's Institutes[19].

1970s–1990s: Green Shield Stamps, Argos, Cash Converters

At the end of this ten-month training session, however, Sainsbury’s departed 9–11 London Road after nearly 90 years at the address[20]. The building may then have spent a brief period as a Green Shield Stamps shop[21], but by 1973 it was an Argos catalogue store[22]. Cash Converters also spent some time at the premises, before moving to numbers 13–15 next door[23].

1999–2013: The Ship of Fools

The Ship of Fools opened on 28 September 1999, joining the many other shop conversions in Wetherspoon’s estate. As with other such conversions, Wetherspoon’s chose a name with a local connection; in this case, the work of the same name by Alexander Barclay, a poet and clergyman who died in Croydon in 1552[24].

Here I declare a bias: I am very fond of Wetherspoon’s pubs. They're unpretentious, they do decent food at reasonable prices, they generally have excellent step-free accessibility, and they have a strong focus on real ales and ciders. Although the London Road branch hasn’t always had the best of reputations throughout its 13 years in West Croydon, under the careful guidance of current manager Liz Tuffey it’s become one of the better examples of the breed.

It’s worth noting that the impending closure of the pub is related neither to the August 2011 riots nor to Sainsbury’s previous ownership of the premises. The plan to offload the property from Wetherspoon’s estate was devised four years ago, partly on the basis of the expense of maintaining the building. It’s also not the case that Sainsbury’s have owned the building all along — they sold it after closing their previous store, and it’s currently owned by a landlord with many other properties around London. Wetherspoon’s originally took out a 25-year lease on the property, but have now transferred the remainder of this to Sainsbury’s[25].

Update, January 2014: When this article was originally written (February 2013), it still wasn't clear when the Ship of Fools would finally be closing — the only thing Liz and her staff had been told was that they’d be given 20 days’ notice[26]. Along with the many other people who used the pub, I knew I’d be very sad to see them go. It finally closed in June 2013, and half a year later I still keep finding myself wanting to go for a drink there.

Thanks to: Liz Tuffey at the Ship of Fools; the Marks & Spencer Company Archive; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; Sean Creighton for helping me avoid a false trail; Gabriel Shepard at the Croydon Advertiser; Leigh Sparks; Marc Bannister; Ray Wheeler; John Clarke; Colin Withey; Tony Skrzypczyk; all at the Croydon Local Studies Library; and my beta-readers bob, Ewan, and Flash.

Footnotes and references

- Information on advertising tokens taken from The Sainsbury Archive on the Museum of London website.

- When built, these were numbered 4, 5, and 6, rather than 7, 9, and 11 (see my earlier article on the great renumberings of London Road). In connection with the piecemeal development along London Road noted in the present article, it’s interesting to note that the earliest-constructed buildings were numbered in such a way as to leave gaps for future development. The oldest street directory I’ve seen that actually gives street numbers for this part of London Road is Gray’s 1851, which jumps straight from number 1 to number 23. Numbers 16–22 appear in Gray and Warren’s 1855, numbers 2 and 3 appear in Gray and Warren’s 1859, and the other numbers are also gradually filled in as more buildings are constructed.

- This piece of land gave its name to the present-day road called Parson’s Mead. Note that as mentioned in a previous article, at some point prior to 1851 the southernmost part of London Road was also called Parson’s Mead.

- Alexander Caldcleugh was the person who built Broad Green House, of which more later in this series.

- Much of the information in this and the preceding paragraph comes from pages 31–35 of Urban Development and Redevelopment in Croydon 1835–1940, Ron Cox, PhD thesis, Leicester, 1970. I have taken a small jump in relating the land to the present-day roads, partially with the help of a plan of Broad Green House and its grounds found in the Harold Williams sales particulars for 1891, consulted at the Croydon Local Studies Library.

- Thanks to Raymond Wheeler and Marc Bannister for help with dating this photo. Ray told me via email (March 2013) that it must be 1901 at the latest, as the image shows a horse-drawn tram and these were replaced in that year. Marc later pointed out (online conversation, July 2013) the differing heights of the canopies on numbers 9 and 11. This image is a scan of a Pamlin Prints postcard in my possession. The postcard doesn't state the name of the photographer, but the same image is used on p15 of the 1890s publication Where To Buy At Croydon (Robinson, Son, & Pike) where it's credited as “from a photo by Frith” (see image on the British Library's Flickrstream). Date of Frith's death taken from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (viewing Frith's entry requires a subscription or a Croydon Libraries library card number).

- According to the senior archivist at the Marks & Spencer Company Archive (personal communication, 2012), 7 London Road was “acquired by Sainsbury's in the early 1880s, who also bought the larger property [i.e. 9–11] next door.” — though I’ve been unable to ascertain the original source of this information. The Story of Sainsbury’s (published by J Sainsbury Limited, April 1969) notes that John Sainsbury certainly wasn’t averse to buying properties and leasing them to others: “Corners were for banks. You might, of course, take a corner site to prevent a competitor getting it but then you’d let it to a bank.” (p18) Microfiche planning records consulted at Croydon Council offices (ref A5038, planning application submitted by Boots) confirm that 7 London Road was still owned by “Trustees of the Late J J Sainsbury” as late as July 1968.

- F A Egleton (furnishing ironmonger) was at number 7, and F Smith, Bon Marché (draper) was at number 9. These businesses were the first to be listed in street directories for their respective addresses, with both appearing for the first time in Ward’s 1882 street directory. Number 11 was still listed as vacant until 1884, at which point John Sainsbury (provision dealer) is first listed. Although there’s always some lag between a business opening up and its being listed in directories (for example, as noted in the main article, John Sainsbury actually opened his shop in 1882), this does still suggest that F A Egleton and F Smith were in place for some time before Sainsbury opened his shop.

- See list of branch opening dates on the Sainsbury’s Archives Virtual Museum website.

- The Story of Sainsbury’s states in a photo caption on p18 that “This was the first shop with which J. J. Sainsbury planned to attract a middle-class trade.” There is perhaps an interesting parallel to be drawn here with the new Sainsbury’s due to open in the same premises this year — is this a signal of impending gentrification for London Road?

- The lack of cleanliness in other grocery shops is according to The Story of Sainsbury’s (p18), though it could of course be pointed out that this is unlikely to be an entirely unbiased source.

- 1882 opening date taken from the Sainsbury’s Archives Virtual Museum list of branch opening dates, and confirmed in several other sources including The Story of Sainsbury’s (photo caption p41), The Best Butter in the World (a history of Sainsbury’s by Bridget Williams; p163), and p4 of the September 1950 issue of Sainsbury’s in-house magazine, the J S Journal (PDF). The Croydon Advertiser article linked at the start of the present article claims an opening date of 1886, but this is simply taken from the Wetherspoon's information board inside the pub, and given the sources above is clearly incorrect.

- The Sainsbury’s Archives Virtual Museum states that the expansion occurred in 1889, but Ward’s street directories list variously-named drapers (Wm. Thos. Morley, Brown & Cameron, and William Evans) at number 9 until 1896. John Sainsbury also had other branches on London Road, at numbers 17 and 35 — more on these later in this series.

- The Story of Sainsbury’s, p20.

- The photo clearly post-dates the mid-1890s expansion into number 9. It also appears on page 24 of the January/February 1992 J S Journal (PDF), with the caption “Delivery tricycles at London Rd, Croydon, 1908.” (thanks to Marc Bannister for discovering this).

- More information on pre-self-service shopping can be found on the Join me in the 1900s website.

- Information in this paragraph comes from The Story of Sainsbury’s, p59–60, and The Best Butter in the World, p124–127. For more details on the thinking behind the self-service experiment, see Fred Salisbury’s article “Sainsbury’s Sample Self-Service” in the September 1950 issue of J S Journal (PDF). I’ll reiterate the point that 9–11 London Road was considered to be a large shop at the time — significantly larger than most of Sainsbury’s other branches. It’s interesting to compare this with the current plan to turn the exact same premises into a Sainsbury’s Local, which is one of Sainsbury’s smaller types of shop.

- The Story of Sainsbury’s (p60) says early July 1950, but this must be a mistake. The Croydon Advertiser piece quoted in the present article is dated Friday 30 June 1950 and states that the self-service branch had opened the previous Monday. The September 1950 issue of J S Journal (PDF) (p1) also gives the opening date as 26 June of the same year.

- Croydon Advertiser, 30 June 1950, viewed on microfilm at the Croydon Local Studies Library. Note the mention of perspex; The Best Butter in the World (p127) points this out (along with fluorescent lighting) as one of the more important innovations that were incorporated in the new Croydon store and later became standard in all Sainsbury’s other stores. See also a set of photos relating to self-service on the Sainsbury Archive Flickr account.

- More information on decimalisation can be found on the Royal Mint website.

- The Best Butter in the World, p163. Date of ending the exercise also confirmed via a small news item in the Croydon Advertiser of 27 November 1970, consulted on microfilm at the Croydon Local Studies Library.

- It appears that 9–11 London Road stopped trading as a regular store a few months before the decimalisation training exercise; the August 1972 issue of J S Journal (PDF) (p47) lists the retirement of a Mrs C Brewin, who “was engaged on May 22, 1967, as a part-time Supply Assistant at 9/11 Croydon, was regraded to part-time Display Assistant in June 1969 and transferred to Central Croydon in November 1969, when 9/11 closed.” The March 1971 issue of J S Journal (PDF) (p4) notes that this “historic branch is now, alas, for sale”, and a planning application dated 26 March 1971 for use of the upper floors as offices describes the building as “Sainsbury’s former premises” (ref 71/20/518, viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices).

- One of the regulars at the Ship of Fools told me that it had been a Green Shield Stamps shop in the past. However, I haven’t uncovered any documentary evidence of this. Croydon phone books from 1971, 1972, and 1973 list Green Shield Stamps only at 34 South End; this is also currently a Wetherspoons pub (the Skylark), so it’s possible my informant was confusing the two. However, absence from the phone book is not proof of absence in real life. The next occupant of the premises was Argos (see next footnote), and Green Shield Stamps and Argos were created by the same person, Richard Tompkins. In a sense, Argos as a catalogue store could be considered a natural development of the Green Shield catalogue shops, so a rebranding of 9–11 London Road from Green Shield to Argos is quite plausible. Further information on Richard Tompkins, Green Shield Stamps, and Argos can be found in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (login required for link, but a Croydon Libraries library card number will do).

- 9–11 London Road is listed as an Argos store in the 1973/4 Argos catalogue (scan provided by Leigh Sparks, Professor of Retail Studies at the University of Stirling). It also appears in Croydon phone books from 1974 onwards, and Goad plans from August 1974 onwards (the Croydon Local Studies library has no Goad plans earlier than this). It’s listed (without a number, but between numbers 7 and 15) in Brian Gittings’ 1980 journal of Croydon shops, and at 9–11 London Road in the 1984–85, 1986–7, and 1988–89 London Shop Surveys.

- Cash Converters is listed at 9 London Road in the first edition of Shop ‘Til You Drop, published by Burrows Communications. This edition is undated, but the copy at the Croydon Local Studies Library has an acquisition date of February 1999 and an unknown person has written “1998” on it. By the second edition of this guide (again undated but with an acquisition date of February 2002), Cash Converters has moved to 13–15 London Road and the Ship of Fools is listed at 9–11.

- Opening date and reason for name taken from Wetherspoon’s website. Date and place of Alexander Barclay’s death taken from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. There seems to be some disagreement over whether Barclay’s Ship of Fools was a translation of, an adaptation of, or simply inspired by Sebastian Brant’s Daß Narrenschyff ad Narragoniam — I am unqualified to judge.

- Information in this paragraph supplied by Liz Tuffey. I’m not sure exactly when Sainsbury’s sold the freehold, nor whether numbers 7 and 9–11 were both sold to the same party. I do know that by 1994 number 7 at least was owned by a company called CHP Management Ltd (planning application 94/1830/A, consulted on microfiche at Croydon Council offices).

- Given the length of time that Wetherspoon’s head office has been planning to get rid of the pub, this lack of information does seem to be rather a harsh reward for the amount of work Liz and her team have put in. Indeed, the Winter ’12–’13 edition of Wetherspoon News carries a full-page article praising Liz’s community spirit and local involvement — with no mention of the impending sale to Sainsbury’s.