Almost entirely vacant since the 2004 demolition of the hospital buildings, the old General Hospital site on the east side of London Road is finally being brought back into use with the construction of a new school.

Pre-1865: the Oakfield Estate

The area around the General Hospital site has been associated with the name of Oakfield since at least 1543, when the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Manor of Croydon Terrier listed one “Thomas Heryngeman in Okefielde” as tenant of an area covering half an acre.[1]

This land would almost certainly have consisted entirely of fields at that point and for some centuries after, but by 1794 a house had been constructed: a “modern built Brick Villa House” accompanied by outhouses, stables, coach houses, gardens, pleasure grounds, a granary, an orchard, a farmyard, cowhouses, sheds, pens, and “other appurtenances”. The “six closes of land adjoining, 23 acres by est. [estimate]” also comprised part of this estate, which “in the whole [...was...] called Oakfield Place”. The occupant was Robert Smith.[2]

1790s–1800s: Elizabeth Panton

In summer 1794, Oakfield Place was sold to Isaac Lefevre for £6,502 [£780,000 in 2015 prices]. Although Isaac was the purchaser, the money came from Elizabeth Panton, and it was she who became the new occupier.[3] Her estate was considered notable enough to be mentioned, along with others, in a guidebook known as The Ambulator:[4]

In this parish, at North End, is Oakfield Place, the seat of Mrs. Elizabeth Panton, and near the town are the handsome villas of Chris. Taddy, Esq. and Lady Blunt, but who does not reside there; near this place John Brickwood, Esq. has an elegant seat, and at no great distance are the residences of the Hon. Mrs. Walpole, Joseph Leeds, Esq. Sir John Bridger, and Thomas Walker, Esq.

As made clear by the map and quotation above, Elizabeth was married. She had, however, “been living apart from” her husband Thomas for “many years”, and they had no children. Thomas himself lived at Newmarket in Cambridgeshire, where he had a large estate inherited from his father (and, according to Charles Pigott’s The Jockey Club, a live-in mistress).[5]

Elizabeth moved to Hampshire around 1804, and died on 2 June 1805. Her will included the “desire to be buried at Poplar in the same Vault with my late Dear Father and Mother in as private a manner as possible”.[6]

1800s–1830s: Charles, Rachel, and William Minier

A brief period of ownership by John Hodsdon Durand followed, but in February 1805 he sold the estate on to Charles Minier.[7] Charles also remained only briefly, but in his case this was because he died in November 1808, “aged about 70”.[8]

It’s unclear what happened to the ownership of Oakfield Place in the years immediately after Charles’ purchase. His last will and testament was drawn up in August 1793, before he bought the estate, and hence makes no mention of it. He left “All the Rest Residue and Remainder of my Estate and Effects both Real and Personal not herein before or herein after by me otherwise disposed of” to his wife Rachel, “for and during the term of her natural life or until she shall marry again”.[9]

Rachel does seem to have spent at least some time living at Oakfield Place after her husband’s death, though also retaining her London house at Adelphi Terrace.[10] She did not marry again, but died a widow in 1838.[11]

By 1812, however, Land Tax records make it clear that William Minier was the only member of the family either owning or occupying property in the area. It seems possible that Charles may in fact have transferred his Croydon property to his brother before his death. William expanded the estate even further, acquiring three more parcels of land in February 1809, February 1813, and May 1813.[12] At some point during this time, too, the house became known as Oakfield Lodge. William died here on 5 September 1835, at the age of 70. His will left Oakfield Lodge and all its “appurtenances” to three trustees who were directed to sell it off “as soon as conveniently may be” after his death.[13]

1830s–1860s: Richard Sterry

The last person to occupy the full extent of the estate, stretching from London Road in the west to St James’s Road in the northeast, and from beyond the modern Kidderminster Road in the north to the railway line in the south, was Richard Sterry.[14] Fittingly, given the later use of the land, Richard was one of the first members of Croydon’s Local Board of Health, elected at its initial creation in August 1849 and serving on the board for the next half-decade.[15] Following his purchase in 1836, Richard and his family lived in Oakfield Lodge until his death on 23 February 1865.[16]

1860s–1870s: The end of the Oakfield Estate

Richard Sterry’s death signalled the end of the Oakfield Estate. Although Oakfield Lodge retained its immediately surrounding gardens, the rest of the land was split up into lots and sold off to housing developers. New side roads were constructed running through the site, including Oakfield Road — the sole reminder today of a name surviving for half a millenium.[17]

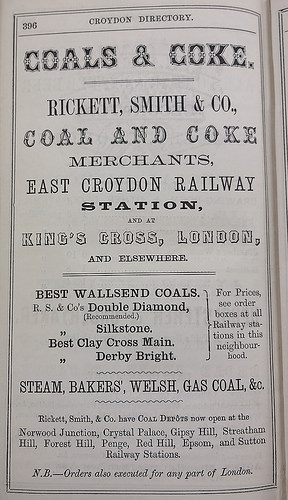

Oakfield Lodge itself, along with its gardens, passed into the hands of Joseph Rickett, a “colliery owner and coal merchant” whose company — Rickett, Smith & Co — had “coal depôts” at major railway stations which allowed commuters to place their coal orders on their way to or from work.[18]

Joseph, his wife Cordelia, and their children remained in Oakfield Lodge for several years while housing gradually rose up around them, lining the newly-constructed side roads.[19]

1867–1873: Meanwhile, elsewhere, the beginnings of Croydon General Hospital

During this carving-up of the old Oakfield Estate, events were occurring elsewhere in Croydon that would soon determine the future of Oakfield Lodge and its gardens. The Croydon workhouse, which had been operating on Duppas Hill Lane in South Croydon since 1727, moved in September 1866 to larger purpose-built premises on Queen’s Road, near the Croydon/Thornton Heath boundary.[21]

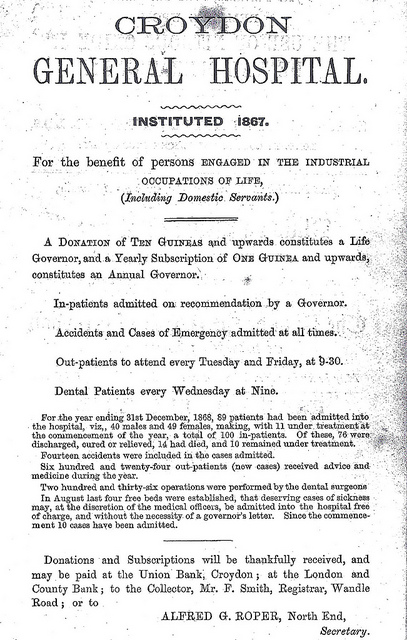

The newly-vacated Duppas Hill premises were taken over by a committee of twelve Croydonians and used to open a hospital on 22 August 1867 for “the relief of those sufferers whose circumstances will not allow them to obtain necessary medical treatment, but whose social position is above that of paupers”.[22]

Paupers would be treated in the workhouse infirmary, which had moved to Queen’s Road along with the workhouse itself, while better-off people would be able to pay for private treatment. The new Croydon General Hospital thus aimed to cater for those in the middle — too poor to pay doctors’ fees, but too well-off to be considered destitute.

According to an article in the 17 August 1867 Croydon Chronicle, “Accommodation [...was] provided for 12 patients” in the new hospital. It had “two commodious wards [...] for the reception of patients”, with a third planned but “not yet [...] fitted up, owing to a lack of funds”, as well as “a convalescent ward, a dispensary, and apartments for the matron, [...] a nurse, and a messenger and his wife, who will act as cook.”

Eligible patients were those “engaged in the industrial occupations of life, (Including Domestic Servants.)” They were expected to make some financial contribution towards their treatment; in-patients were charged 3 shillings per week, while out-patients were charged sixpence per week (£16.10 and £2.68 respectively in 2015 prices).[23]

Aside from accidents and emergencies, and those considered deserving enough to secure one of the “four free beds” established in August 1868, in-patients were admitted only with a letter of recommendation from a hospital governor. Becoming a governor required either a life subscription of at least 10 guineas, or a yearly subscription of at least a guinea (£1,127 or £113 respectively in 2015 prices).[24]

1873: The General Hospital moves to London Road

The Duppas Hill premises were only leased on a temporary basis, to give “the opportunity of testing the necessity for hospital accommodation”.[25] This necessity proved to be a real and significant one; in 1868 alone, 89 patients were admitted, 624 others received outpatient treatment, and 236 dental operations were performed.[26] It was clear that permanent premises would be needed, and this became more urgent as the Croydon Board of Guardians notified the hospital committee that they would soon need to reoccupy their old workhouse.

In 1871, a building committee was appointed to choose a location for the new hospital. Several options were considered, including Blunt House on South End, Duppas House near the parish church, and sites at Addiscombe and Duppas Hill, but the committee finally settled on Oakfield Lodge and its grounds.[27]

This choice of site was not universally popular. The Croydon Chronicle of 4 October 1873 noted that:[28]

Many will remember the “battle of the sites” which took place among the committee, and it was not without some little dismay that Oakfield Lodge was heard of as the spot fixed upon. Taken from the Hospital point of view, it is unexceptional; but viewed from the point at which holders of property in the immediate vicinity will take, it is altogether objectionable. In reality, there is nothing in a Hospital detrimental to the neighourhood in which it is placed, but there is a dislike to it which is difficult to allay. There must also be a feeling of disappointment that such a building, standing as it does in magnificent grounds, is lost as a residential place to the town.

It was also not cheap. Joseph Rickett originally asked for £12,000 for Oakfield Lodge and its grounds, and although building committee member Dr Alfred Carpenter managed to persuade him down to the price he had originally paid for it — £10,305 — another £1,300 was estimated as the cost of converting the house to a hospital, making a total of £11,605 (£1.2m in 2015 prices).[29]

The purchase was completed on 1 March 1873, and following alterations designed by architect J Berney, the new hospital was opened by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 27 September.[30]

1880s onwards: Expansion

The hospital rapidly outgrew its new premises, and by the early 1880s it was clear that more space was required, as “the kitchen and offices, the operating ward, house surgeon’s rooms, out-patients’ department and dispensary, and other important administrative arrangements of a hospital were crowded into a range of outhouses and stables. The medical staff [...] pressed for the complete alteration of this portion”.[31]

The foundation stone of the Royal Alfred Wing was laid by the Duke of Edinburgh in November 1883, and the wing was opened by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 15 October 1884. As well as the new facilities described above, this increased the in-patient capacity of the hospital from 30 to 50 beds.[32]

Further expansion took place in the remaining years of the nineteenth century, with a new wing on the east side opened in October 1894 and “the rebuilding of the administrative block and yet another extension [...] formally opened by H.R.H. Princess Christian in 1900.”[33]

Following a fundraising campaign led by the Mayor of Croydon “in memoriam of the late King Edward VII”,[34] in 1912 the Royal Alfred Wing was extended and another new wing added, the King Edward VII Memorial Wing. The British Journal of Nursing reported that:[35]

For some time past the work of the hospital has been hampered by the absence of isolation wards and the limited accommodation for its new departments. This has now been remedied as the result of the Mayor’s ardent efforts in the cause.

1910s onwards: Collaboration with the County Borough of Croydon

It should be remembered that Croydon General Hospital was independent of the County Borough of Croydon. Indeed, it came under some criticism from the latter’s Medical Officer of Health, who stated in his report for the year 1908 that:[36]

[...] the excellent work done by the General Hospital is somewhat marred by the fees demanded from out-patients, a system to which there are many objections, of which the chief — from our point of view — is the fact that many children are thereby deprived of the special help which an institution of this kind, with its excellent equipment, can alone afford. Thus the Health Visitors sometimes find that, after hospital letters have been procured, the children are refused treatment because they have not brought the necessary sixpences, and this is particularly the case when treatment is prolonged, or when more than one member of a family is in need of advice.

Nevertheless, the two bodies did provide some services in collaboration with each other. A treatment centre for venereal diseases was established in late 1917, initially treating only women and children aged up to 18 but extending its services to men from early 1920. The centre dealt with 103 cases in its first full year, including 53 of syphilis and 31 of gonorrhea. It was situated in Croydon General Hospital’s outpatient department, but funding came from the Borough.[37]

June 1918 saw the creation of a throat clinic specifically for surgical treatment of enlarged tonsils and adenoids in school children, with all cases being referred by school nurses. Croydon’s Medical Officer of Health reported approvingly on this in his report for 1919, stating that “This institution saves the parents much trouble and expense. Formerly many of the children were taken to London hospitals, which often have long waiting lists.” It was run by the Borough’s Education Committee, which rented space at the hospital.[38]

1920s: A new pathology laboratory and outpatient departmemt

By 1922, the Borough’s Tuberculosis Officer was sending patients to Croydon General Hospital for x-rays to aid in diagnosis.[39] The Borough had its own hospital, dedicated to infectious diseases, which had opened in 1896,[40] and in 1924 plans were announced for a new pathology laboratory as a collaboration between the Borough Fever Hospital and Croydon General. This would be situated at Croydon General, but staffed with a pathologist salaried by the Borough, and would perform laboratory work for both bodies.[41]

The new laboratory was opened by the Archbishop of Canterbury on 25 June 1927, along with a new outpatient department “built from brick [...] with a decorative stone frontage under a slate roof” and “lined [inside] with tiles of a soft green shade”.[42]

1948: The National Health Service

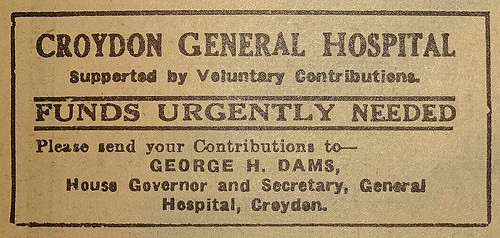

Until the creation of the National Health Service, Croydon General Hospital was entirely privately-funded; indeed, the façade of the abovementioned 1920s outpatient department bore the prominent legend “Supported by Voluntary Contributions”. As well as fees paid by patients, money came from donations, endowments, subscriptions, and fundraising events.

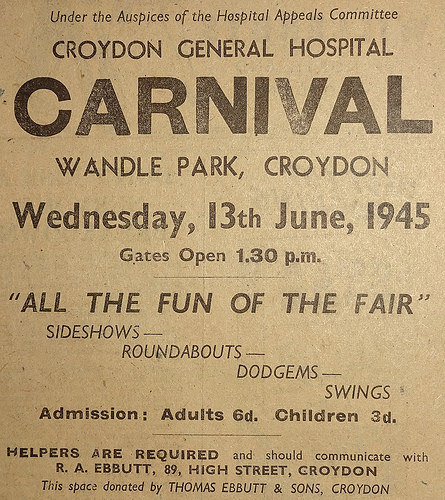

In 1945 alone, fundraising efforts included a carnival in Wandle Park, attended by “Thousands of Croydon people” who “cheerfully dug deep into pockets and handbags to help swell the funds of Croydon General Hospital”,[44] a “Victory ball and cabaret” which raised over £2,000 (£77,863 in 2015 prices),[45] the launch of a “Penny-a-Week Fund” (16p in 2015 prices),[46] a bowling club gala day which raised nearly £350 (£13,626 in 2015 prices),[47] and a whist drive.[48]

The same year also brought cash donations from individuals, churches, golf clubs, home guard regiments, workplace collections, and box collections, as well as various ad-hoc donations including toys, children’s books, magazines, sweets, books, writing paper, cigarettes, lavender bags, tin foil, chocolate, powdered milk, cakes, jam, fruit, vegetables, bread, and even a pumpkin.[49]

In 1948, however, Croydon General finally became a publically-funded body, as it joined the NHS “under the control of the Croydon Group Hospital Management Committee, part of the South West Metropolitan Regional Health Board”.[50]

1960s: Roger Perriss’ memories

Roger Perriss, who took a summer job at Croydon General as a hospital porter after leaving school in 1966, shared some memories of this time:[51]:

The porters had a basement room with access just by the main front door. There were usually 2 or 3 porters on each shift, so between 9.00 & 5.00 the numbers of porters doubled [due to overlap between shifts].

I remember arriving once at 6.00 [for the early shift] and before the other porter arrived I got a phone call to remove a body from a ward. You used a trolley with a closed metal top that hid the body from sight. I had to wait until the other porter arrived before we could do the task. When you got to the ward the curtains were pulled around all the beds (about 15 in a ward) so that those in beds did not see you arrive or leave. Of course you could be heard.

The mortuary was across a yard from the wards and you had to be accompanied by a nurse until you had entered the mortuary. It always seems strange to me that some nurses, who must have dealt with patients dying, nevertheless were nervous about entering the mortuary. I think it held about 12 bodies. [...]

I also remember that the hospital had about 6-8 wards and there were two private wards on the top (second) floor. If a patient needed a abdominal shave before an operation, the porters would be called to do this on the men’s private ward and were paid a sum, I think it may have been 10 shillings. I was only asked to do this once. I already had a beard at that age and so when I arrived to do the shave on a man, he assumed that I was experienced at this kind of shaving but it was my one and only ever shave on that part of the body. He asked me “Do you do many shaves?” I replied “Not many,” and nervously got on with it.

If you were on the evening shift you might be asked to go over to the nurses’ homes across the road at the rear and man the switchboard for the evening. There were not many calls and it was mostly just taking messages or getting a nurse to come and speak to the person. I used to think it was a fairly easy evening’s work. Though to be fair, the evening shift in the main hospital was not a busy one. There were two porters that were permanently on night shifts so they arrived when the day porters left. I thought it must be strange working nights all the time.

There was a small accident and emergency department on the road side, left of the main entrance. The porters occasionally went there to take patients onto wards but I don’t remember doing this often.

1980s: Funding difficulties

In December 1982, the Croydon Advertiser reported on a “plan to open the new Mayday by approving massive bed closures at almost all Croydon’s other hospitals.” One of the “[w]orst hit by the plan” would be the “170-bed Croydon General Hospital, which would stop operations and be used for geriatric patients instead”. The report stated that “The crisis has been caused by a Government ban on extra cash for health services improvements.” According to “hospital administrators”, savings of £2m would be needed in order to fully open the new buildings constructed as part of the Mayday Hospital modernisation plan.[52]

By early 1984, this plan had been put into action, as 73 geriatric patients were transferred from Waddon Hospital, which itself was to close for good. This took up less than half the capacity of Croydon General, which now had three wards sitting completely empty.[53]

1990s: The final closure

As well as the need to save money, the hospital now had to contend with changes in professional opinion on the most appropriate way of caring for older people. In July 1990, the Croydon Health Authority Director of Public Health told a meeting of the Croydon Community Health Council that:[54]

“The length of stay in geriatric beds has been inappropriately long and are [sic] no good to patients. We want to have shorter lengths of stay.”

Shorter lengths of stay would, obviously, mean less need for hospital beds. While arguably good for the individuals, who would now be “looked after at home or in private nursing homes”,[55] the effect on Croydon General would be rather less beneficial.

A consultation document published by Croydon Health Authority shortly after the abovementioned meeting made it clear that “action [...had...] already started” on moves including “Running down Croydon General itself”. Despite a 5,000-signature petition asking for the hospital to remain open, the last in-patient left in September of that year.[56] Out-patient treatment continued for a few years longer, but the last clinic finally closed in July 1996.[57] The Croydon and Carshalton College of Nursing, which had occupied the old wards after their closure to in-patients, moved out a couple of months later.[58]

1990s–2000s: Plans for the future

Several suggestions were made for new uses, prompted not only by the waste of such a central location but also by the six-figure yearly capital charge imposed by the NHS on the empty hospital buildings. Croydon Community Health Council produced a six-page report suggesting options such as rental to voluntary groups, office use by the local health authority, and even parking. However, the condition of the buildings made most of these implausible, as the health authority’s executive director explained to the Croydon Advertiser in July 1997:[59]

“There is no longer any heating, for a start,” he said. “And unfortunately we had burst pipes last winter, the weekend before maintenance staff were due to go in and drain down the system.”

Although a public meeting at Fairfield Halls voted overwhelmingly to sell the site, and Croydon Health Authority agreed to declare the site surplus and allow the NHS to sell it, no progress had been made on this by the end of 1998.[60] By mid-1999, alternative proposals had been drawn up to build a new centre for rehabilitation and mental health services on part of the grounds,[61] and the business plan for this was given formal approval by the Croydon and Surrey Downs Community NHS Trust in March 2000.[62]

In September 2002, Croydon Council published a planning and design brief for the old General Hospital site, offering non-statutory guidelines for future development of the site. As well as the proposed uses for rehabilitation and mental health care, these guidelines included “the provision of high density residential development [...] including a significant element of affordable housing” with environmentally-friendly features such as rooftop solar water heaters, triple glazing, and rainwater and greywater recycling. A combined urban sculpture park and playground was also suggested, “[b]uilding on the drama of the existing mature cedar tree”.[63]

Early 2000s: Deterioration

Throughout this, the old hospital buildings remained standing, though in a dilapidated state. The chief officer of Croydon Community Health Council described them in April 2001 as “largely decaying”, noting that “It pulls down the whole image of the area to see it in that state.”[64], while a February 2002 Croydon Advertiser article stated that the buildings had “remained in a sorry state for years” and were now “festooned with graffiti”.[65] Little had changed two years later, when a letter to the Croydon Guardian bemoaned the fact that the “valuable site [...] disintegrates year by year [...and...] has become an eyesore for people on their way through litter-strewn streets [...] used only by mountaineering graffiti scribblers”.[66]

2004: Demolition

Croydon Council’s 2002 planning and design brief assessed the “main hospital building” as being “imposing, but not of great architectural significance” and the other buildings on the site as being “of no particular architectural merit”. However, it praised the “well detailed stone façade” of the outpatients department, and recommended that this should be retained in any redevelopment, along with other features such as the London Road boundary, consisting of “a low wall with well detailed railings over, with entrances marked by substantial brick and stone piers”, as well as “stone entranceways, porticoes, columns, carved stone panels and two commemorative stones (on the front elevation of the main building and the rear elevation of the veranda)” and three mature trees: a lime, a plane, and the abovementioned cedar.[67]

It’s unclear how much of an attempt was made to follow the council’s recommendation of retaining stonework features when demolition finally began in June 2004, though bricks, timber, and tiles were salvaged to help offset costs.[68] By October, the old General Hospital had been reduced to “a crumbling old building surrounded by rubble”,[69] and demolition was complete by the end of the year.[70]

2006–present: Croydon Voluntary Action

The grand plans for medical facilities and hundreds of housing units, drawn up as long ago as 1999, eventually came to nothing. However, one aspect survived. The proposals had included the setting-aside of “a corner of the site” for a Healthy Living Centre, a “£75,000 drop-in centre aimed at helping people to help themselves to a healthy lifestyle”.[71] By April 2001, the estimated cost of this had risen to £1.5m, and Croydon Community Health Council along with another body, Croydon Voluntary Action, had already begun to raise funds.[72]

By mid-2004, the project was being referred to as the Healthy Croydon Resource Centre, and local voluntary groups were eagerly looking forward to its opening. The Croydon Advertiser reported that:[73]

Dozens of local health and welfare groups have already expressed interest in using its facilities, which will include conference and meeting rooms, activity spaces, a cafe and offices.

Early interest has been enthusiastic.

Elizabeth Njenga, from the Kikiwa Counselling Centre, which helps African refugees, said: “It is very hard to get suitable office accommodation in Croydon, especially in a good location which people can get to easily. We are looking forward to this development.”

Plans now included 16 flats, nine of which were intended to be offered via a shared ownership scheme.[74] Work began in early 2006 and continued until at least mid-2008.[75]

By September 2008 the flats were being advertised under the name of “Zed Space”, available “to residents of Croydon on a part rent, part buy basis”, and by March 2009 Croydon Council’s Your Croydon magazine was advertising the facilities available in what was now known as the Croydon Voluntary Action Resource Centre:[76]

Whether your organisation needs to rent an office or book rooms for meetings or seminars, new space is available for rent from Croydon Voluntary Action at the CVA Resource Centre in London Road, Broad Green. It is open to voluntary organisations and social enterprises.

It has rooms for meetings and training sessions plus a board room or conference room for more formal events. The centre can accommodate anything from small regular or one-off meetings to conferences and exhibitions.

The centre was formally opened on 29 July 2009 by Croydon councillor Steve O’Connell and Volunteer Centre Croydon co-founder Angela Bothwell.[77]

2014–present: Harris Invictus

In early 2013, the Harris Federation was given approval to open a new secondary school, Harris Invictus, under the coalition government’s “free schools” concept — schools which, although publically funded, are not under the control of local government.[78] This opened in September 2014 in temporary portacabins on the eastern side of the General Hospital site, with entrance via Lennard Road. Meanwhile, construction of a permanent school began on the rest of the site.[79] At the time of writing, this is still ongoing, but work is hoped to be completed by September 2017.[80]

Thanks to: Brian Mortimer; Brian Simmons; Carole Roberts and Cathy Aitchison, for research advice; John H Meredith; Paul Talling of Derelict London; Stiles Harold Williams; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers bob and Shuri. Census data consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Administrative note: Regular readers may have noticed that according to my article-every-four-weeks schedule, this one should have gone out on 17 June. I decided to postpone it a couple of weeks because the previous one, on Stonemead House, ended up being nearly twice as long as usual, so I thought people might want more time to read it. The present article is even longer, and so the next one in this series will appear on Friday 12 August.

Footnotes and references

The Manor of Croydon Terriers were three surveys of the lands owned by the Archbishops of Canterbury within Croydon parish. The Museum of Croydon has the original copy (ref AR36) as well as a transcription made by C G Paget. More information can be found on the Museum of Croydon’s Collections website.

Aileen Turner’s History of Broad Green (available at the Museum of Croydon under shelfmark S70 (9) TUR) has a quotation on page 493, attributed to the 1493 survey: “along North End to the Kynges Highwaye to London and where the eastern side consists of large antient enclosures, one called Oakfield, and then on to Brode Grene Gate.” However, I haven’t been able to find this in Paget’s transcription, and it’s not anywhere obvious in the original either.

- Details and quotations taken from C G Paget’s transcription of a lease and release dated 30 June/1 July 1794 (Paget’s notebook 19, page 278, viewed at the Museum of Croydon). It should be noted that in all cases where I cite Paget’s notebooks, I am relying on the accuracy of the transcription as I haven’t viewed the original documents.

- Date of purchase, price, and identity of purchaser are taken from the 1794 lease and release cited above. A deed poll similarly transcribed by C G Paget (Paget’s notebook 19, page 289) makes reference to an indenture dated 2 July 1794 in which “it was declared that the purchase was for the use of Elizabeth Panton and made with her money”.

- This quotation appears on page 95 of the 10th edition of The Ambulator, published by Scatcherd and Letterman in 1807 (viewed online at Google Books). The full title of the book is The Ambulator: or, a Pocket Companion in a Tour Round London, Within the Circuit of Twenty-Five Miles: Describing Whatever is Remarkable for Antiquity, Grandeur, Elegance, or Rural Beauty. (Its information was, however, somewhat out of date, as Elizabeth had not only moved out of Oakfield Place by 1807, but also died.)

Quotations and name and residence of Elizabeth’s husband taken from a deed poll transcribed by C G Paget (Paget’s notebook 19, page 282). Item C 13/602/25 on the National Archives website suggests that Elizabeth and Thomas separated around 1769. Information on their lack of children is taken from the report of a High Court of Chancery case on 6 March 1809 (Bird vs. Le Fevre), which states that Elizabeth “died on the 2d of June, 1805, not having had any issue” (on page 591 of Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the High Court of Chancery, Volume 15, by Francis Vesey Jr, viewed as PDF from Google Books). Thomas’s father was also called Thomas; his will was proved on 17 January 1783 (viewed on Ancestry.co.uk, which gives the source citation as “The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1099”). Newmarket is no longer (partly) in Cambridgeshire, but fully part of Suffolk.

Thomas and his father were notable enough to be included in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Thomas’ entry can be viewed online by logging in with a Croydon Libraries library card number. Elizabeth is not mentioned. The National Portrait Gallery also has a picture of him (ref NPG D11249). Information about his mistress is taken from The Jockey Club, Part 1 by Charles Pigott (5th edition, published 1792, page 92, viewed as PDF via Google Books), which refers to him as “Tommy P--t--n” and states that “He has lived many years very domestically with a lady, whose name is unknown to us, but of whose personal charms it is not in our power to speak very favourably”; and moreover that “He was, during a considerable time, the cher ami of the celebrated Mrs. M------y, and we believe he has a natural son, now an officer in the Horse Guards, but whether by the above lady or not, we are ignorant.”

- The 1795 Land Tax Record (viewed online via Ancestry.co.uk) lists “Mrs Panton” as both proprietor and occupier of a “House &c” in the “Bensom” (later Bensham) area of Croydon parish, rateable at £16/3s/4d. She continues to appear in these records up to and including 1803. The 1804 record instead lists J H Durand, and records from 1805 onwards list Charles Minier. A notice on page 778 of the 11 June 1805 London Gazette describes Elizabeth as being “late of Oakfield-Lodge, Croydon, in the County of Surrey, and since of West-Green-House, near Hartford-Bridge, in the County of Hants, deceased”. Her date of death is taken from the Bird vs. Le Fevre case cited above. Her will, which also gives her father’s name as Elias Bird and confirms her residence at “West Green in the County of Hamphire [sic]”, was proved on 16 January 1806; see my transcription of the probate register copy (National Archives reference: PROB 11/1437/116). Note that the probate register itself contains transcriptions of the original wills, and hence the “Hamphire” mistake could have originated from the probate transcriber.

- The Conditions of Sale given in particulars for a sale of the estate on 23 June 1865 state that the title “as to the mansion house and the greater portion of the land [...] will commence with indentures of lease and release dated the 12th and 13th of February, 1805, being a conveyance on sale to Charles Minier, late of the Adelphi Terrace, in the parish of St. Martin in the Fields, in the county of Middlesex, deceased.” (The reason for the specification of “the greater portion of the land” is that later owners expanded the estate by buying more land.) Further evidence for John’s and Charles’ ownership comes from the 1804 Land Tax Record (viewed online via Ancestry.co.uk), which lists J H Durand as proprietor and owner of the same house and land previously listed under Elizabeth Panton’s name, and the 1805 Record, which lists Cha[something] Minier (see earlier footnote); the latter of these is dated 1 July 1805. An indenture of lease and release dated 23 July 1836 (Paget’s notebook 19, page 237) confirms that John Hodsdon Durand occupied the house after Elizabeth, and that Charles Minier followed him.

- Charles Minier’s death is reported in the 30 November 1808 Bury and Norwich Post (page 4, last column, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). It also appears in the Gentleman’s Magazine Historical Chronicle For the Year 1808, Part 2 (page 1130), which gives the additional detail that he died on 22 November “At his brother’s house, Adelphi terrace, Strand, aged about 70” (viewed as a PDF via Google Books).

- Charles Minier’s will viewed via Ancestry.co.uk, which gives the original source citation as “The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1491”.

- The 11th edition of The Ambulator (published 1811) describes Oakfield Place as “the seat of Mrs. Minier” (page 84, viewed as a PDF via the Internet Archive). Moreover, a Mrs Minier appears in the 1810 and 1811 Land Tax records for Bensham, along with a Minier (likely William); it isn’t, however, clear who was living in the house. (Their surname is spelt “Minnier” in 1810, but corrected in 1811.)

- The Ancestry.co.uk England, Select Deaths and Burials, 1538-1991 database states that Rachel Harvard Minier, aged 74, was buried at Westminster on 26 October 1838 (ref v1835-46 p140).

- Information on William’s land purchases is taken from the Conditions of Sale given in particulars for a sale of the estate on 23 June 1865. William acquired “34 perches (or thereabouts) of land” via “an indenture or deed of feoffment on sale by the vicar, churchwardens, overseers of the poor, and six inhabitants of Croydon” on 28 February 1809. He then bought “2 roods and 32 perches (or thereabouts)” from the Croydon Canal Company via “indentures of lease and release dated the 19th and 20th of February, 1813”, and “4a. 0r. 4p. [4 acres, 4 perches] (or thereabouts)” from the trustees of “the late Sir Nicholas Hackett Carew, Bart. [Baronet]” via “indentures of lease and release dated the 6th and 7th of May, 1813”.

- William’s date, age, and place of death are reported in the 14 September 1835 Reading Mercury (page 3, column 4, viewed online via the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). His age and place of death are also given in the 19 September 1835 Oxford University and City Herald, though without a date (page 1, column 3, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive). His will was dated just two days before his death, and proved less than a month later; see my transcription of the probate register copy (National Archives reference: PROB 11/1852/91). This will and these two reports are the earliest citations I’ve found for the name “Oakfield Lodge”, as opposed to “Oakfield Place”.

Extent of the estate as owned by Richard Sterry is assessed from the 1844 Tithe Map and a couple of plans included in sales particulars from 1866 and 1867, viewed at the Museum of Croydon. The 1866 plan is in the collection of loose sales particulars (ref CR2615), and the 1867 plan is in the maps drawers (map 12 in drawer 39; the textual parts of the relevant sales particulars are in Harold Williams 1867 volume, ref DCLIX). Richard increased the size of the estate freehold very slightly after he bought it from William Minier’s trustees, by purchasing “six and a half perches (or thereabouts)” from the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company on 14 December 1850 (see the previously-cited 1865 sales particulars, ref CR2640) but it seems likely that this had been previously part of the estate under lease from “the Company of the Proprietors of the Croydon Canal” since 1810 (see Paget’s notebook 19, page 236).

Some further idea of the size of the estate at this time can be gained from later reports that Richard Sterry maintained a deer park on part of his land; Old & New Croydon Illustrated, a Croydon Advertiser special edition published in May 1894, states under the heading of “Croydon General Hospital” that “Richard Sterry [...] in his time kept deer in what was then really and truly Oakfield Park”, while Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past (published 1883) states on page 106 that the estate “was formerly a deer park” (it should be noted that these two sources are not entirely independent, as Jesse Ward was the publisher of the Croydon Advertiser).

- Gray’s 1853 Directory of Croydon states on page xxii that the Local Board of Health was “first elected in August, 1849” and that the members at the time of writing included “Richard Sterry, Esq., ‘Oakfield Lodge.’” Old & New Croydon Illustrated lists “Mr. R. Sterry” as a board member from 1849–50 to 1856 inclusive under the heading “The Croydon Local Board of Health” (unfortunately this publication has no page numbers).

Richard initially leased the estate for a period of one year, but before the year was up he bought it from William Minier’s trustees for the sum of £9,550 (£984,000 in 2015 prices); see C G Paget’s transcription of an indenture of lease and release dated 23 July 1836 between parties including William’s trustees, William’s widow, William’s ward, and Richard himself (Paget’s notebook 19, page 236). He and his wife Ann, along with various children and servants, are listed at Oakfield Lodge in the 1841, 1851, and 1861 censuses.

The GOV.UK “Find A Will” search records Richard as having died at Oakfield Lodge on 23 February 1865. According to Jesse Ward’s Croydon in the Past, he was buried at the Friends’ Meeting House, where as noted in my article on 95 London Road several headstones still survive today. However, I was unable to locate Richard’s; either it wasn’t one of those saved, or it has since worn down to unreadability. I did find a stone for Mary and Sarah Sterry, but according to the 1851 census they lived at 35 Addiscombe Road, and Croydon in the Past doesn’t mention any connection between them and Richard. They could have been relatives, or this could have just been a coincidence of surname.

- See my article on 60–62 London Road for a few more details on what happened to the land immediately after Richard Sterry’s death.

Aileen Turner’s History of Broad Green states on page 498 that “The house itself with the gardens reaching to Lennard Rd and covering about the same area as the present hospital buildings and surround was let to Mr Rickett, a colliery owner and coal merchant and who also opened a series of little offices in the lock-up shops mostly built by the railway companies next to or near the stations used by the commuters, so the Man of the House (!) [sic] could order the coals while dashing to of [sic] from his train. [...] Mr Rickett stayed until the final sale to the Croydon Hospital Committee in 1873”. No references are given for any of this, and I’m not entirely certain it’s correct in saying that Mr Rickett rented rather than bought the premises, since it seems clear (see later in article) that the General Hospital committee paid him a considerable sum of money for it.

“Mr Rickett”’s first name is taken from the 1871 census. His connection with Rickett, Smith & Co is taken from the caption to a photo in the Museum of Croydon’s collection of photos of the General Hospital; this is clearly a page (page 26) cut out of a publication, but there are no details of what the publication is, aside from a year (1896) written in pen in one corner. The phrase “coal depôts”, along with confirmation that these were at railway stations, is taken from an advertisement on page 396 of Warren’s 1869 Directory of Croydon (reproduced here).

- The 1871 census lists Joseph Rickett, aged 51, “Share & Bond Holder” (and some other unreadable words); his wife Cordelia, aged 44, and five children aged from 2 to 20.

I identified the estate and hospital site boundaries by comparison of maps including the 1844 Tithe Map, the 1896 Town Plans, and the 1954 Ordnance Survey map, as well as the layout of the houses on Oakfield Road today. It appears that the hospital later re-acquired a little of the surrounding land to both north and south, including the plots on the south side marked here as Lots 9 and 10; these latter were the site of Lennard Lodge, which housed Croydon Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services until 2012 but has now been demolished (personal observation; see also my photo of the building in August 2012).

An article on page 3 of the 11 October 1884 Croydon Chronicle mentions purchase of “land and premises [...] on the north side of the Hospital” in connection with construction of the new Royal Alfred Wing (see main article), but it’s unclear exactly where this was. The nearly-empty rectangular strip just inside the north edge of the dashed hospital boundary on the 1867 map looks plausible. However, this is clearly shown as a “Nursery” in the 1896 Town Plans and listed as “Nursery”, “Royal Nursery”, or “Florist” in Ward’s directories from 1874 to 1924 inclusive, and hence must have either been bought freehold for the benefit of the ground rent paid by the leaseholder (possibly but unlikely, as I’ve found no mention of this strategy in the many detailed newspaper articles which discuss the hospital’s funding) or been acquired later.

- For more information on the Croydon workhouse, see Peter Higginbotham’s The Workhouse website. Some sources place the Duppas Hill workhouse on Duppas Hill Lane; others on Duppas Hill Terrace. Warren’s 1865–66 directory lists 7 Duppas Hill Lane as being “Used as a temporary Infirmary for the ‘Croydon Union’”.

- Size of hospital committee taken from a short piece in the preface of Warren’s 1869 Directory of Croydon (pages xxxix–xl). Quotation and date of opening taken from an article in the 17 August 1867 Croydon Chronicle (viewed on microfilm at the Museum of Croydon).

- Patient charges taken from an article on page 273 of the 4 September 1869 British Medical Journal describing the second annual meeting of the Croydon General Hospital committee (viewed online via the US National Library of Medicine).

- Quotation, information on in-patient admission and governorship criteria taken from an advert in Warren’s 1869 directory (reproduced here). All price conversions made with 1869 as base year.

- Quotation taken from a speech by Mr A G Roper, honorary secretary of the hospital committee, given at the September 1873 opening of the London Road premises and quoted on page 2 of the 4 October 1873 Croydon Advertiser (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription) as well as in the Croydon Chronicle of the same date. According to the abovementioned 17 August 1867 Croydon Chronicle, the hospital committee had initially leased the premises for three years beginning on Lady Day (25 March) 1867.

- Figures taken from an advert in Warren’s 1869 directory, and apply to “the year ending 31st December, 1868”. According to a short piece in the preface of this directory (pages xxxix–xl), the dental surgeons of the hospital were Samuel Lee Rymer and Joseph Steele, both of whom later lived on London Road and are discussed in my articles on the Lidl site and 95 London Road, respectively.

- Croydon Chronicle, 4 October 1873.

- Viewed as a set of photocopied clippings in the General Hospital clippings file at the Museum of Croydon.

- Croydon Chronicle 4 October 1873. Further information about Alfred Carpenter can be found on the General Practitioner Memorials website.

- Croydon Chronicle 4 October 1873.

- “The Royal Alfred Wing of the Croydon General Hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 October 1884, page 3.

- “The Royal Alfred Wing of the Croydon General Hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 October 1884, page 3, partially corroborated by an untitled piece on page 3, column 2 of the 16 October 1884 London Evening Standard (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). The latter article also states that “The Hospital now [...] has over 5000 in and out patients”. It’s not clear what this figure actually refers to, but it may be an estimate of the number of patients that the hospital would be able to treat per year now it had its new wing.

- “Croydon General Hospital”, Croydon Times Souvenir Issue, 10 June 1933, with additional details supplied by the mysterious “page 26” photo from the Museum of Croydon collection, referenced in an earlier footnote. According to an article on page 2 of the 13 March 1909 Croydon Guardian (“Reminiscences of his Public Life”), the new wing opened in 1894 consisted of “the Mary and Mark Wards”.

- “Croydon General Hospital”, Croydon Times Souvenir Issue, 10 June 1933.

- British Journal of Nursing, 27 July 1912, page 74.

- County Borough of Croydon Annual Report on the Health and Sanitary Circumstances of Croydon [...] For the Year 1908 (page 104, viewed online via the Wellcome Library).

- County Borough of Croydon Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer for the years 1917 (page 72, viewed online via the Wellcome Library), 1918 (page 23, viewed online), 1919 (page 79, viewed online), and 1921 (pages 12 and 13, viewed online).

- County Borough of Croydon Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer for the years 1918 (page 100, viewed online), 1919 (page 120, viewed online), and 1921 (page 13, viewed online).

- County Borough of Croydon Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer For the Year 1923 (page 29, viewed online).

- Further information on Croydon Borough Hospital can be found on the Lost Hospitals of London website and in the Corporation of Croydon Report of the Hospital Department for the Official Year ended 31st March 1895 (viewed online via the Wellcome Library).

- County Borough of Croydon Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health and School Medical Officer For the Year 1924 (pages 26–27, viewed online).

- Date of opening, Archbishop of Canterbury’s involvement, and second quotation taken from an article on pages 171–172 of the July 1927 British Journal of Nursing (Vol 75 No 1908). First quotation taken from Croydon Council’s 2002 planning and design brief (see later footnote).

- Note that the year on the façade is 1926; Lost Hospitals of London states that this was the year in which the foundation stone was laid. According to an article in the Croydon Times Souvenir Issue of 10 June 1933, construction began in 1925 and the formal opening was on 25 June 1927 (see also earlier reference to the July 1927 British Journal of Nursing).

- Croydon carnival gets going again”, Croydon Times, 16 June 1945, page 5.

- “Brilliant scenes at hospital ball”, Croydon Times, 14 July 1945, front page.

- “Hospital’s fine war record”, Croydon Times, 21 July 1945, page 3.

- “Counting the cash”, Croydon Times, 28 July 1945, page 5.

- “Whist drive for hospital”, Croydon Times, 22 September 1945, page 3.

- “Croydon General Hospital”, Croydon Times: 6 January 1945, page 3; 27 January 1945, page 3; 24 February 1945, back page; 21 April 1945, page 3; and 11 August 1945, page 3.

- Lost Hospitals of London.

- Via email, 19 November 2014. I have removed a few passages for reasons of space, and also added extra punctuation in a couple of places.

- “Shock plan for bed closures”, Croydon Advertiser, 3 December 1982, front page.

- “Empty wards”, Croydon Advertiser, 17 February 1984.

- “Conspiracy claim over General Hospital closure”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 July 1990, page 14.

- “Conspiracy claim over General Hospital closure”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 July 1990, page 14.

- “Residents brand hospital consultation a ‘farce’”, Croydon Advertiser, 12 October 1990, page 2, column 3.

- “Last patient ends philanthropists’ dreams”, Croydon Advertiser, 19 July 1996, page 9.

- The moving-out of the nursing college is mentioned in “Last patient ends philanthropists’ dreams”, Croydon Advertiser, 19 July 1996, page 9, and confirmed in “Empty hospital incurs thousands in charges”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 July 1997, page 13.

- “Empty hospital incurs thousands in charges”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 July 1997, page 13. This article states the charge as being £300,000, while another the following year (“Town picks up tab for unsold hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 December 1998, page 8) gives a figure of £400,000. A letter from the chief officer of the Croydon Community Health Council, published in the 14 April 2000 Croydon Advertiser (page 19) states that by that time the charge had risen to £500,000.

- “Town picks up tab for unsold hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 December 1998, page 8.

- “Health chiefs to consider new development plans for surplus hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 27 August 1999, page 4.

- “£4.5m rehab centre on landmark site moves a step closer”, Croydon Advertiser, 31 March 2000, page 14.

- The Croydon Council planning and design brief was initially published as a draft in February 2002, and following public consultation was adopted in its final form on 23 September 2002. The draft version is available in paper form at the Museum of Croydon (Green box s70 [362] CRO [General Hospital]) and the final version is available in PDF form at the Internet Archive. It notes on page 22 that many of the environmentally-friendly features proposed were already in use at the BedZED development in Sutton. Quotations are taken from pages 20 and 22. Articles covering aspects of the public consultation include “Hospital plans upset residents” (Croydon Guardian, 6 March 2002, page 9) and “Croydon General views sought” (Croydon Guardian, 22 May 2002, page 5).

- “Plea to reopen old hospital fails”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 April 2001, page 6.

- “Health village scheme aims to revitalise old hospital site”, Croydon Advertiser, 8 February 2002, page 17.

- Letter from Margaret Evans, Croydon Guardian, 25 February 2004, page 20.

- See earlier footnote for details on the Croydon Council planning and design brief. Quotations are taken from the final version, Part 3, pages 11–14.

- Date of demolition start is taken from “Bulldozers move in on hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 11 June 2004, page 19. Information on salvage is taken from “Work begins on demolishing old general hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 9 July 2004, page 2; the latter article also describes the demolition as a “five-month project”.

- “The street tarnished further by killings”, Croydon Advertiser, 8 October 2004, page 2.

- “Green future for old hospital site”, Croydon Advertiser, 10 June 2005, page 6.

- Quotations taken from a letter from the chief officer of Croydon Community Health Council, published in the 14 April 2000 Croydon Advertiser (page 19), and “Health chiefs to consider new development plans for surplus hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 27 August 1999, page 4, respectively.

- “Plea to reopen old hospital fails”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 April 2001, page 6.

- “Bulldozers move in on hospital”, Croydon Advertiser, 11 June 2004, page 19.

- “Green future for old hospital site”, Croydon Advertiser, 10 June 2005, page 6.

- Date of start of work taken from “Work gets under way on community centre”, Croydon Advertiser, 17 February 2006, page 14. Situation as of mid-2008 assessed from Google Streetview imagery from July 2008.

- Information on Zed Space taken from an advertisement on page 5 of the 19 September 2008 Croydon Advertiser. Your Croydon magazine downloaded as a PDF from the yumpu.com online publishing platform.

- Information taken from memorial plaque in the foyer of the CVA Resource Centre (see photo in main article).

- “Government gives thumbs up to three new free schools”, Croydon Advertiser, 24 May 2013, page 8.

- “‘We’re aiming to be outstanding’”, Croydon Advertiser, 10 October 2014, page 18. Location of temporary site and entrance via Lennard Road are from personal observation.

- The Admissions page of the Harris Invictus website states that “The permanent building for Harris Invictus Academy Croydon will not now be ready for the school to move into until the 2017/18 academic year.” (accessed 31 May 2016).