Together with its car park — and the employment tribunal offices at the corner — the Lidl branch at 99 London Road takes up a full 100m of road frontage, almost exactly the same as the old General Hospital site across the road. The history of the land, however, is rather more diverse.

1830s–1850s: Initial development

I’ve described before how the previously-common land to the west of this part of London Road was brought under private ownership in the 1820s before being auctioned off in lots in 1835. As with the rest of the land, the plots that later became the Lidl site were bought by a number of different people and hence developed at different times.[1]

The purchasers of these particular plots were John Blake, W S Owens, and Samuel Bendry Brooks. John was the first to develop his land, having built a pair of houses on it by 1844, but the others were not much slower, and by 1851 there were seven houses on the combined plots, nestled between North End Lodge to the south and the newly-constructed Montague Road to the north. A couple of years later, another two houses were added on Samuel’s land, bringing the total to nine.[2]

An impression of these houses can be gained from a notice of sale in the 9 May 1868 Croydon Chronicle, which describes one of them as:[3]

A semi-detached Residence, in a capital position, with a carriage sweep, and row of trees in the front, and walled-in garden behind, well stocked with standard and trained fruit trees, &c. The house contains on the upper floor, three bed-rooms and dressing-room; on the first floor, two large cheerful bed-chambers, and a dressing-room; on the ground floor, good entrance hall, front dining-room and drawing room, overlooking the garden, both of good height and proportions. The usual offices in the basement and side entrances for tradespeople.

1840s–1850s: Samuel Selmes

One of the earliest inhabitants was Samuel Selmes, who lived in the third house from the south. Previously a farmer in Beckley, Sussex, Samuel had grazed “one of the most admired herds in the county” over 5,000 acres of “rich marshlands” before retiring from farming in 1848.[4]

A letter published in the Carlisle Journal of 2 January 1841 provides an example of such admiration:[5]

The uniform health, vigour, and merit of Mr. Selmes’s stock, as a whole, is to my mind quite astonishing; uniting as they do such an aptitude to fatten, with the requisite stamina to lean flesh, cannot but establish their characters as ready feeders and great weighers[.]

He was admired for more than his cattle, however; on his retirement, “about thirty of the owners and occupiers of the parish” presented him with a set of silver plate “[in] testimony of the high esteem with which they have for many years regarded his public and private worth, as an enterprising agriculturalist, a kind and warm hearted friend, a benevolent and humane master, and as an honest and exemplary man.”[6]

Samuel was living on London Road by 1849, but had little time to enjoy his retirement, as he died on 27 November 1852 at the age of 80. His wife Ann survived him by four years, dying on 11 July 1856 also at the age of 80.[7]

1850s–1870s: Frederick Samuel Hopkins

Another early resident — and, similarly, a retiree — was Frederick Samuel Hopkins, who lived in the northmost of the nine houses, on the corner with Montague Road. Indeed, according to Jesse Ward’s Croydon in the Past, Frederick himself was responsible for the building of this “excellent residence”. He was “a most retiring and amiable gentleman” who moved to Croydon on his retirement from business in London, and served for some time as a Poor Law Guardian. His daughter Elizabeth later married Samuel Lee Rymer, who will be discussed below.

Frederick moved to London Road with Elizabeth and his wife Mary by 1851, and lived there until his death on 17 October 1878, in his late 80s. Mary, of a similar age, survived him by only a matter of months, dying at home on London Road on 15 May 1879. Both were buried in Queen’s Road Cemetery.[8]

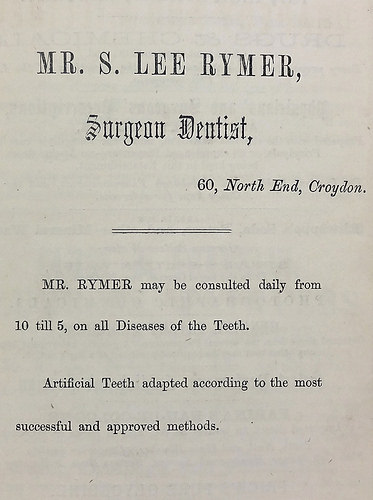

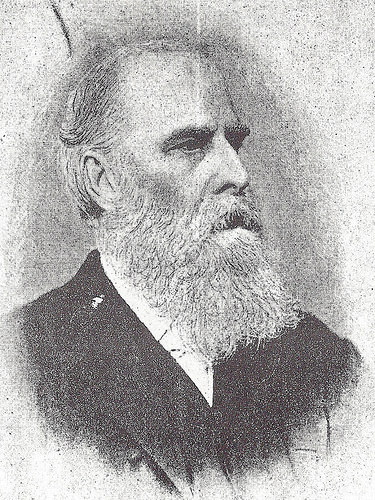

1870s: Samuel Lee Rymer

Perhaps the most well-known inhabitant of the nine houses was Samuel Lee Rymer. Born in Plymouth on 5 May 1832, he trained as a dentist before moving to Croydon and setting up in practice on George Street around 1853.[9] He married Elizabeth Gresham Hopkins in 1856. Samuel and Elizabeth moved to London Road in the early 1870s, two doors down from Elizabeth’s father Frederick, and remained here until the early 1880s, when they moved to Wellesley Road.[10]

At the time Samuel entered the profession, dentistry was neither a well-organised nor a well-regulated industry. It was “relatively undeveloped as a clinical specialism[...], text-books were few, and formal teaching of the dental art was singularly lacking.” Moreover, there were essentially two types of dentists; “on the one hand there was a small group of educated men who held medical and/or surgical qualifications, and on the other hand a large group of uneducated and unqualified persons”.[11]

Although far from the first practitioner to see a need for dental reform, Samuel was the first to act publically and decisively.[12] Still only in his mid-20s, he began with a letter to the editor of the Lancet, published on 25 August 1855, in which he described some of the harm caused by incompetent dentists, noted the existence of Colleges of Dental Surgery in America, and proposed that such a college should be set up in his own country.[13] A public meeting followed on 22 September 1856, at which a committee was formed to work on two tasks: to create a “society of dentists [...for...] promoting the advancement of dental science”, and to establish “an authorised system of professional education and examination”.[14]

This meeting also saw the emergence of a surprising fact, previously unknown to most of those present — “several leading members of the profession” had already privately approached the Royal College of Surgeons on the matter of “a special course of lectures for dentists”. There were thus two groups working for dental reform, though in rather different ways. The essential differences were that Samuel’s group looked for the establishment of dentistry as an independent profession, and worked publically and democratically; whereas the other sought affiliation with and recognition from an existing establishment, the aforementioned Royal College of Surgeons, and worked primarily in private.[15]

Despite Samuel’s enthusiasm, hard work, and strong level of support among his peers, it was ultimately the other group that succeeded in their aim. A major sticking point in their endeavours was removed when the 1858 Medical Act made it legal for the Royal College of Surgeons to hold examinations for dentists, and the first such examinations were conducted in 1860.[16]

Samuel took defeat graciously, and in May 1863 the two rival groups were amalgamated under the name of the Odontological Society of Great Britain.[17] Samuel himself obtained his own Licence of Dental Surgery from the Royal College of Surgeons, and served a term of office on the council of the Odontological Society.[18] He later became a founding member of the British Dental Association, and was elected its President in 1889.[19]

Aside from his work on national matters, Samuel was active locally. Along with his colleague Joseph Steele, he provided dental services at Croydon General Hospital, which opened in 1867 and moved to permanent premises just opposite Samuel’s London Road house in 1873.[20] He was elected to the Croydon Local Board of Health in 1870, and continued to serve until 1883, when this body was superseded by the newly-incorporated County Borough of Croydon.[21]

At the first Town Council election on 9 June 1883, Samuel became one of six councillors for the Central Ward, and at the first meeting of the new Council he was made an alderman along with eleven of his colleagues including Joshua Allder, founder of Allders department store, and John Thrift, a grocery wholesaler who had been a neighbour of Samuel’s during the latter’s time on London Road. Samuel became a Justice of the Peace at the formation of Croydon’s board of magistrates in 1885, and was elected Mayor of Croydon on 9 November 1893.[22]

He was also, at various times, treasurer and vice-president of the Croydon Conservative Association, honorary secretary and president of the Croydon Literary and Scientific Institution, chair of the Board of Governors of the Whitgift Foundation, and one of the founders of the Croydon Guardian newspaper.[23] Samuel remained an alderman, councillor, and magistrate for the rest of his life. He attended his final council meeting on 1 February 1909, but “a day or two later had to take to his bed” with pneumonia. He died at home early in the morning of Sunday 7 March 1909, just a few weeks before his 77th birthday, and was buried at Queen’s Road Cemetery in the same grave as his wife Elizabeth.[24]

A selection of other inhabitants[25]

A few of the other inhabitants of the nine houses are discussed in more detail in other articles in this series. Costumiers E & J Stubbings were in the southernmost of the houses from c.1892 to c.1899, and are covered in my article on number 76. Surgeon Henry Horsley lived in Samuel Lee Rymer’s old house from c.1907 to c.1915, and is covered in the same article. Dr Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith lived in Samuel Selmes’ old house from c.1903 to c.1921, but practised down the road at number 61.

While the predominant use of the houses was as private residences, there was the occasional business use too, including private schools. Before its occupation by E & J Stubbings, the southernmost house was a school, first for girls (Boswell House, College for Young Ladies, c.1883-c.1884, run by Miss Pearse and then Miss Porterfield) and then for boys (Charles Robert Good, Boarding & Day School for Young Gentlemen, c.1885–c.1891). Between its occupation by Samuel Lee Rymer and Henry Horsley, the third house from the north was also a school for young ladies, run by Mrs H M Feist from c.1886 to c.1894, with the addition of a “class for little boys” taught by Miss Feist.[26]

1913: Arrival of the Croydon Co‑operative Society

The southernmost two of the nine houses both fell vacant around the end of the 1890s, and remained so for the next dozen or so years. By September 1912, however, the Croydon Co‑operative Society had begun negotiations to purchase them for conversion to a new store and headquarters.[27]

This Society originally began trading on Church Street in 1887. It “had as its ideal, the spirit of co-operation; a system whereby persons with small incomes can combine with others more favourably situated, to become part owners in the business, and reap, together, the profits of its trade and investments.”[28] It opened a branch at Thornton Heath around 1904, by which point its membership had grown to around 800 people.[29]

In 1907, the Society moved its main premises from Church Street to 64 London Road, a single shop property owned and recently vacated by the pawnbroking company Bowman Ltd. Expansion was soon on the cards, with the two houses across the road being only one of the options open to the Society; its current freeholder, Bowman Ltd, was keen to sell it not only number 64 but also the neighbouring 66. However, on 25 April 1913 the Society’s Committee unanimously passed a motion agreeing to purchase the two houses for £2,500 (£260,000 in 2015 prices) — significantly less than the £5,500 Bowman had wanted for its two shops.[30]

Frank Bethell was chosen as the architect, and purchase of the new premises was completed in June 1913. In August of that year, eight building firms were invited to tender, and on 25 September it was decided the builder would be Albert Monk of Edmonton, who proposed completion by 25 January 1914 at a cost of £4,100 (£427,000 in 2015 prices).[31]

1913–1914: Labour disputes

Albert Monk’s tender was both the lowest offer and the one proposing fastest completion; in accepting it, however, the committee may have failed to take into consideration whether the builder was in sympathy with their co-operative principles. In November 1913, the Carpenters & Joiners Trade Union wrote to the committee “complaining of the employment of non-union men on the new buildings”. The Society’s response was that “the Committee have no control so long as the Trade Union rate of wages is paid.”[32]

While there seems not to have been any mention of strike-breaking on that occasion, this was not the case a few months later, when the Society’s committee meeting minutes recorded the attendance of a deputation from the Croydon Trades & Labour Council at the 13 February 1913 committee meeting:[33]

They each addressed the Committee and complained that non-union men had been taken on at the New Buildings in place of those on strike [“in sympathy with those locked out in London”] and suggested that the Committee should take the work out of the hands of the Builder & complete it themselves.

Again, the Society had no recourse: “The position was explained to them and the Deputation withdrew.”[34]

Two weeks later, a requisition signed by 22 members was presented to the committee, calling for a Special General Meeting “in order to consider the action of the Committee in connection with the strike on the building of the new Central Premises”.[35] This meeting took place on 18 March, attended by “the whole of the Committee and a large number of members”, but nothing was resolved. One resolution was presented, that those attending the meeting were:

[...] of the opinion that the best interest of the Society would have been promoted if the General Committee had definitely decided to have the works on new Buildings closed during the present dispute in the Building Trades of London.

However, the Chair “regretted that he could not accept it” to be voted on, due to lack of advance notice. Following a “general discussion [...] as to the Chairman’s ruling and the policy of the Committee in connection with the building dispute”, the Chair reiterated “the position of the Committee” to the meeting, which was then adjourned.[36]

By mid-April, the new premises were “approaching completion”, and interviews for staff had begun.[37] However, work was again halted by strike action, this time by those working on the shopfronts and interior fittings. The committee wrote to the Building Trades Federation “asking if there was any probability of the men being allowed to work and if not had they any suggestions to offer.” A reply was received a month later, stating that the work could “proceed on the understanding that the work was taken out of Mr Monk’s hands and completed with direct labour after his plant had been removed.”[38]

The members of the Society had not been silenced by the meeting of 18 March. A letter was received in May from a Mr A James asking for a resolution to be placed on the agenda of the next half-yearly meeting, calling for:[39]

the President, Secretary & Committee to resign on Consequence of their Anti Trade-Union Policy in allowing the Contractor to proceed with the erection of the new premises with black-leg labour.

The next month, however, Mr James wrote again to withdraw his resolution, possibly influenced by the Committee’s decision to work with the unions to resolve the most recent strike. Matters seem to have become more amicable by this point, as the Committee decided that “Mr James [should be] thanked for the trouble he had taken.”[40]

1914: Opening of the new Croydon Co‑operative Society premises

The end was finally in sight, as the Buildings Sub-Committee reported on 19 June 1914 that the new premises “were sufficiently advanced as to justify the announcement of the opening on Thursday July 16th”. The Committee decided that “each of the trade unions in Croydon” should be invited to the opening ceremony.[41]

The Croydon Advertiser and Croydon Guardian both reported on the opening, describing the “shops, arcades, and offices” as “spacious and lofty” and mentioning “waiting rooms, an extensive dispatch department, and a refreshment room”. One speaker, Mr H G A Wilkins (a director of the Co‑operative Wholesale Society), took the opportunity to state that:

He wanted the people of Croydon to realise the difference between their shops and those of large companies with multiple shops. In the latter case, a few capitalists who had already plenty of money would take a little money out of Croydon to swell their large bank balances, and as a rule they were the worst paymasters in the district. In the case of the Co‑operative Society, however, where the conditions of employees were generally the best in the district, profits were returned to the people of Croydon who were members.

The opening ceremony was followed by tea in the lecture hall of West Croydon Methodist Church, accompanied by music from the London Brighton and South Coast Railway Prize Band.[42]

1910s–1930s: Merger with other Co‑operative Societies, and further expansion along London Road

At the time of opening its new central premises, the Society had 3,000 members and at least two branches. The President, speaking at the opening ceremony, expressed the hope that “as the result of the opening of the new premises [...] there would still be a much larger increase.” His wish was granted, as by 1916 membership had doubled to 6,000 and the Society boasted a total of eight branches.[43]

July 1918 saw the merger of the Croydon Co‑operative Society with two other Societies: Bromley and Crays, and Penge and Beckenham. All three were “relatively small but perfectly sound and solvent”. Upon amalgamation, they took a new name — the South Suburban Co‑operative Society (SSCS) — and the Croydon Society’s existing premises on London Road became their head office.[44]

Around this time, the SSCS began slowly expanding northwards along London Road. By 1920, it was using the northern half of the semi-detached pair next door as a warehouse, and by 1923 it had the southern half too (previously occupied by Samuel Selmes and then Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith).[45] The next pair northwards, and the southern half of the pair north of that (previously occupied by Samuel Lee Rymer and then Henry Horsley), had also been swallowed up by 1933, leaving only two of the original nine houses still standing between the SSCS store and Montague Road.[46]

As of 1935, the South Suburban Co‑operative Society had 142,374 members and 67 branches, covering a territory of 400 square miles (over 1000 square km). Its annual sales were £3.2 million (£205 million in 2015 prices), and it paid out £225,540 (£14.5 million) per year in dividends. Its headquarters and flagship store provided a prominent landmark on London Road, the uniform frontage making a strong contrast to the rather more organically-shaped General Hospital opposite.[47]

1940s onwards: Expansion to the south and to Montague Road

The expansion did not end there. Around the start of the 1940s, the large century-old house to the south of the site was demolished and four new shops built. It’s unclear whether these shops were owned by the SSCS when first built, but by 1950 the Society was using them for “greengrocery, junior miss, special baby linen and pharmacy”.[49]

In the early 1950s, the SSCS acquired the remaining land between its premises and Montague Road, including the two remaining of the original nine houses. The southernmost of these houses was demolished by 1954. Its neighbour, built a century before by Frederick Samuel Hopkins, remained standing for now, though in a derelict state.[50]

It seems to have taken quite some time for the SSCS to actually develop this land. Various planning applications were submitted up until at least the end of the 1960s, but all were either withdrawn or refused.[51] By the mid-1970s, however, the Society had expanded its premises at least over the land previously occupied by number 113, and was using the address 99–113 London Road.[52]

Memories of the Co-op

Terry Coleman, a long-term Croydon resident, shared his memories of the London Road Co-op in the 1940s and 1950s:[53]

There was a manager who was immaculately dressed in pinstripes, waistcoat, watchchain, silvergrey hair and walked around the store talking to customers and generally keeping an eye on things [...] You could buy practically anything in the store, groceries, hardware, clothing, furniture, haberdashery of course. That was just the ground floor, upstairs was a dentist, opticians, insurance broking and all the admin etc for the store. There were lifts between the floors, the old lattice door type.

The Co-op had a peculiar system for cash handling at point of sale, there was a vacuum tube arrangement with cylinders that transported the cash to a central office and returned any change and receipt to the salesperson to hand to the customer.

There was a dividend system, similar to the loyalty schemes today but I think you had to be a member of the Cooperative Society to partake [...] mum used to send me down to the Co-op on errands, with instruction from Nan ‘don’t forget the divi number’ which was a six digit code that you gave when you bought the goods and you ultimately got some credit back, no swipe cards then.

Dave Harwood, who was born in Mayday Hospital in 1948 and lived on Kimberley Road until 1970, also remembered the Co-op’s cash handling system, but his memories of the details differ from Terry’s:[54]

From my memory of the London Road Co-op in the 1950’s, it wasn’t vacuum tube operated but a system of wires leading to a central cash office. The cash was put into a container by the salesperson and then twist-locked into a carriage suspended below the wire with two wheels above the wire. It was then catapulted along the wire to the central cash desk for processing. Any change and a receipt was returned by the same method. It made a very memorable “swishing” noise as it travelled along the wire.

Finally, the Croydon Oral History Society publication Talking of Croydon: Shops and Shopping 1920–1992 includes memories from another Croydon resident, May:[55]

In the big Co-op along London Road opposite the General Hospital they had one of their departments transformed into a Christmas gift area and Father Christmas was usually to be found at the back in a grotto, right through the middle of the toys. Once it was a diamond mine!

1980s: Demolition and rebuilding

By the early 1980s, the SSCS was struggling. It was incurring losses of £3.7m per year (£11.2m in 2015 prices), and as the Management Committee’s January 1982 report to members stated, it lacked “sufficient properly equipped modern shopping facilities” and much of its real estate had “become outdated through changing business and social conditions.”[56]

Attempts were made to recover from this, including the launch of a specialist deli and butchery chain called “Bon Appetit”, the conversion of unprofitable grocery branches to electrical and video shops, the opening of a new superstore at Penge, and a reduction in staff numbers. However, the January 1984 report to members admitted that these attempts had failed:[57]

[...] closing of units in the previous year and subsequent opening of a new superstore have not had the desired effect of reducing the Society’s losses. Increased competition within our trading area coupled with the continuing decline in gross margins, particularly in the grocery business[,] have taken their toll”.

The Management Committee now recommended a completely different solution — a merger with the Co‑operative Wholesale Society, a separate body which was the precursor of today’s Co‑operative Group. This recommendation was approved and confirmed at two Special General Meetings, and the merger took place in July 1984. The Royal Arsenal Co‑operative Society (RACS) joined the merger in February 1985, and a couple of months later the administrative offices of both the SSCS and the RACS were consolidated at the latter’s premises in Woolwich.[58]

With the departure of the SSCS administration, much of the office space at 99 London Road became redundant, and the store itself must also have been showing signs of age. The decision was made to demolish it and rebuild in a more modern fashion — including a car park with space for 500 cars. By mid-1985, the grand old building had been vacated for good.[59]

The new Co-op store was open by early 1992, 85 years after first moving to London Road in 1907. It fell just short of a century on the road, however, as in 1999 the premises were taken over by another supermarket chain — Lidl.[61]

1999–present: Lidl

Originating as a grocery wholesaler in Germany in the 1930s, Lidl opened its first retail store in 1973 and expanded to the UK in 1994. Today, it has over 600 stores across the UK. Primarily known as a discount store, it “takes pride in providing top quality products at the lowest possible prices”.[62]

Reporting on the opening of the first UK stores in late 1994, The Grocer magazine described it as a “German discounter” and compared it to Aldi, another German chain which entered the UK around the same time. Details taken from “Local Press advertisements” included the wage rate of £4/hour (£7.17/hour in 2015 prices) and indications that the stores would be run “in the Aldi style of part-timers sharing all floor level duties from checkouts to cleaning and shelf-filling”, and using an “all-scanning” system that meant staff would “not have to wrestle with the price memory system”.[63]

Like many other shops on London Road, the West Croydon branch of Lidl was badly damaged by looters in the August 2011 riots, to the point where it was forced to operate from a temporary structure in the car park during the resulting eight months of repairs. However, the newly-refurbished store was reopened by the Mayor of Croydon on 5 April 2012, and four years later is still going strong.[64]

2000s–present: Fitness First and easyGym

Around the same time as Lidl’s takeover of the main supermarket building, planning permission was granted for the use of “part of ground floor and first floors as [a] health and fitness centre”. By January 2001, this was open as Fitness First, a chain of private gyms with over 130 branches throughout the world.[65] Facilities at the Croydon branch included an air-conditioned gym with “a full range of cardiovascular and strength training equipment” and “[l]uxurious changing rooms”, a spa pool, a sauna and steam room, a “Sound Wave Therapy Chair”, sunbeds, and even a hairdressing service.[66]

Fitness First closed some time between July and December 2012, but the space was taken over by another gym company, easyGym, which opened in April 2013 and is still there at the time of writing.[67]

1992–present: South London Employment Tribunal

The late-1980s/early 1990s redevelopment of the site had also included the construction of new offices along the London Road frontage. These were soon occupied by the South London Employment Tribunal, which moved in on 21 December 1992 from its previous premises on Ebury Bridge Road, Pimlico, and remains there today.[68]

Thanks to: Brian Simmons; Dave Harwood; Martin Stitchener; Terry Coleman; the Bereavement Services at Croydon Crematorium; the Lidl UK Press Office, the National Co‑operative Archive; the South London Employment Tribunal; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers Alice and bob. Census data consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Administrative note: As I mentioned at the end of my article on Croydon General Hospital, for articles that are significantly longer than usual, I’m postponing the following article by a couple of weeks. The present article is another long one, so the next one will be published on 23 September 2016.

Footnotes and references

- See my article on 21 London Road, part 1 for more information, and my article on 95 London Road for an excerpt of a plan from the 1835 auction showing three of the four plots that later became the Lidl site (to the right of the rightmost highlighted piece).

Names of plot purchasers are from cross-referencing the handwritten notations on a copy of the particulars for the 1835 sale (viewed at the Museum of Croydon, ref BA268) with the 1844 Tithe Award (also viewed at the Museum of Croydon). W S Owens appears to have sold his plot on to John Blake by the time of the Tithe Award, so I don’t know his full name (though, oddly, the name “Owens” does appear as the owner of this land in the October 1858 Poor Rate book; perhaps John simply had the lease in 1844).

The 1839 New Valuation of Croydon Parish makes no mention of John’s houses, which suggests they were built between 1839 and 1844; and a brief notice on page 4 of the 23 November 1841 County Chronicle, Surrey Herald, and Weekly Advertiser for Kent describes how a “diabolical villain” broke into “two houses now building by Mr. J. Blake, of Croydon, in Parson’s Mead” and destroyed “four marble chimney pieces in the principal rooms”, apparently “in revenge from Mr. Blake having contracted with London tradesmen for the erection of the houses”. The Tithe Award explicitly lists John as the owner of these houses, and Major Strait and William Scott as the respective occupiers.

Number of houses and existence of Montague Road in 1851 are taken from Gray’s 1851 Directory of Croydon. Montague Road does not appear on the 1844 Tithe Award map; its later location is simply the boundary between plots 652 (building ground owned by Samuel Bendry Brooks) and 652a (a meadow owned by Henry Overton). Regarding the later addition of two more houses, these appear as “Semi-detached residences, erecting” in Gray and Warren’s 1855 directory, and as being occupied by William Edward Acraman and John Baines in the next (1859) edition. “W E Acraman” and “Baines” also appear in the October 1858 Poor Rate book, so must have been there by then. Unfortunately it isn’t clear from the Poor Rate book who owned the land, as the relevant column has been left blank in both this and later editions; I use the phrase “Samuel’s land” in the article merely to identify its location.

- Viewed as a clipping in the London Road — West Croydon roads file at the Museum of Croydon. This refers to “No. 36, London Road”, which was renumbered to 71 in 1890 before being swallowed up in the Co-op building (which itself was renumbered to 99–105 in 1927).

- “The Sussex breed of cattle in the nineteenth century”, J P Boxall, The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 20, No. 1 (1972), pp. 17-29, available as a PDF on the British Agricultural History Society website. The information on Samuel Selmes, and the phrases quoted here, are on page 26.

- Letter from John Bunting, Carlisle Journal, 2 January 1841, page 3, column 5, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription).

- “Presentation of plate to Mr. Samuel Selmes, late of Knell”, Kentish Gazette, 2 January 1849, page 3, column 1, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription). The article notes that the silver plate consisted of “four corner dishes of massive silver fitted up with water reservoirs, complete. The handles of the covers were of frosted silver with emblematical groups of the implements and produce of agriculture.”

- Daw’s 1849 directory lists “Selmes esq” on Parsons Mead. Several of those listed as his neighbours on London Road in later directories are also present, so despite the designation as Parsons Mead I’m pretty confident this is our Samuel Selmes (this directory has no listing for “London Road”; it also has no street numbers). He then appears at 37 London Road (the third of the nine houses, counting up from south to north) in Gray’s 1851 directory. Gray’s 1853 directory lists just his wife, “Mrs. Samuel Selmes”. Dates and ages at death of Samuel and Ann Selmes are taken from Croydon in the Past, page 70, which adds that they were buried together in St James’s Churchyard.

- Frederick S Hopkins, “gentleman”, is listed in directories from Gray’s 1851 to Ward’s 1878 inclusive, some of which give his full middle name as “Samuel”. His wife and daughter are included with him in the 1851 census. The GOV.UK “Find A Will” search confirms that he died at his London Road house on 17 October 1878 (and adds the information that Samuel Lee Rymer was one of the executors of his will). Mary’s name and her age (86), date, and place of death are taken from an announcement in the 24 May 1879 Croydon Advertiser (page 4, column 6, viewed online via the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). All other information, and both quotations, taken from page 149 of Jesse W Ward, Croydon in the Past: Historical, Monumental, and Biographical, 1883 (viewed online at the Internet Archive). This source gives Frederick’s age at death as 87, whereas an announcement in the 21 October 1878 London Evening Standard gives it as 88 (page 1, column 1, viewed online via the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). I haven’t been able to find out what type of business Frederick conducted — Croydon in the Past simply says “He was a ‘monarch retired from a London business,’”, the 1851 and 1861 censuses list him as a “Fund Holder” (i.e. a person with private investments), and the 1871 census has an unreadable phrase which might begin “Property...”.

- An article in the August 1876 Monthly Review of Dental Surgery (“Leaders in the Dental Profession.—No. 1.”, Volume 5, Number 3, pages 105–110, viewed online via the Internet Archive) states that Samuel Lee Rymer was was born at Plymouth on 5 May 1832, studied dentistry under Mr W Perkins and Mr Howse, and began practising at Croydon at the age of 21. An article in the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser (“Death of Alderman Rymer”) provides the additional detail that Mr W Perkins was “Mr. William Perkins, dental surgeon, of Baker-street, Portman-square”. Gray’s 1853 Directory of Croydon lists Samuel Lee Rymer, dentist, at 26 George Street. The 1861, 1871, and 1881 censuses also confirm his place of birth as Plymouth, and give his age as 28, 38, and 48 respectively, which is consistent with someone born in 1832 after April (this being the month in which these censuses were taken).

- Samuel Lee Rymer is listed at 41 London Road in directories from Wilkins’ 1872–3 to Ward’s 1880 inclusive, and at 7 Wellesley Road from 1882 onwards. He, his wife Elizabeth, and nine children aged between 7 and 23 are listed at 41 London Road in the 1881 census. (The 1871 census has their predecessor, William H Horniman.) Date of their marriage is taken from an article in the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser. Ward’s 1882 directory in combination with the 1896 Ordnance Survey 1:1056 map places their Wellesley Road house just to the south of Walpole Road, which itself is just south of where Wellesley Road tram stop is today.

- N David Richards, “The Dental Profession in the 1860s”, in Medicine and Science in the 1860s: Proceedings of the Sixth British Congress on the History of Medicine, University of Sussex, 6-9 September 1967, viewed online via the Wellcome Library.

- Chapter 2 of Alfred Hill’s History of the Reform Movement in the Dental Profession in Great Britain During the Last Twenty Years (1887; viewed online via the Internet Archive) describes a great deal of letter-writing, pamphlet-publishing, and resolution-passing from 1841 onwards, all to little immediate effect.

- The full text of Samuel’s letter to the Lancet can be viewed online at the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society website.

- History of the Reform Movement in the Dental Profession, Chapter 3. Quotations are taken from pages 43–44. This source also states (page 42) that the meeting was chaired by “Mr. Alfred Carpenter, M.B.”; this is almost certainly the Alfred Carpenter who later worked with Samuel at Croydon General Hospital.

- History of the Reform Movement in the Dental Profession, Chapter 3, pages 44 and 57.

- See The Birth of Modern Dentistry: Legislation on the King’s College London website. Technically, the Bill simply made it legal for the Queen to grant powers to the Royal College of Surgeons to hold these examinations, rather than granting these powers directly, but the end result was the same.

- “The Dental Profession in the 1860s”, page 278.

- History of the Reform Movement in the Dental Profession, Chapter 10, section on “Mr. Rymer”.

- Ken Harman (2003), “Samuel Lee Rymer”, Bulletin of the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society, 118: 5–10, viewed online at the CNHSS website. See also List of Presidents on the BDA website.

- An article on the General Hospital in the preface of Warren’s 1869 Directory of Croydon (pages xxxix–xl) states that “The dental surgeons are, S. L. Rymer, esq., and J. Steele, esq.” See my article on Croydon General Hospital for more. Joseph was Samuel’s professional partner from 1869, and also his near neighbour for a few years in the late 1870s, as Joseph lived at the abovementioned North End Lodge for a while.

Old & New Croydon Illustrated, a supplement published by the Croydon Advertiser in May 1894, includes lists of the initial composition and year-by-year elections of the Croydon Local Board of Health. Each year, four of the twelve members would retire “by rotation”, though it appears they could stand for re-election immediately. “Mr S. L. Rymer” first appears as an unsuccessful candidate in 1858, with only 377 votes compared to the 750–887 votes each gained by the four men elected. (An article on page 9 of the 11 March 1909 Croydon Chronicle puts his failure down to the fact that “those were the days when young men were not allowed to display too much enthusiasm”.) He then appears in the lists of successful electees in 1870, 1873, 1877, 1880, and 1883. As there was no election in 1875 “owing to the change in the law regulating the times of Elections, and making them concurrent throughout the country”, this implies that he was re-elected every time he was obliged to stand down. For more on the Croydon Local Board of Health, see the Museum of Croydon website.

Samuel, incidentally, was initially opposed to Croydon’s incorporation as a County Borough. According to a column published in the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser just after his death, his opposition was based “chiefly on the question of the rates, which he considered must inevitably go up, especially when money would be wasted on such matters as the Mayor’s chain and other such foibles.” However, he “quickly and generously acknowledged” that he was “wrong in his view on this subject”. The Mayor’s chain “was bought by the voluntary subscriptions of the members, and a consolidation of the loans, and the spreading of their repayment over many years, not only prevented an increase in the rates, but brought them down in wholesale fashion.” (It’s not clear exactly which body the “members” here were members of — possibly the Board of Health? — nor which loans are referred to.)

- Information on Samuel’s election as Central Ward councillor, alderman, and mayor is taken from Old & New Croydon Illustrated. Information on his magistracy is taken from his obituary on page 6 of the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser, which states that he had “sat [...] on the Borough Bench since its establishment”, and another article on page 2 of the 13 March 1909 Croydon Guardian, which states that he was “one of the original Justices of the Peace for the borough, his appointment taking place in 1885.”

- Ward’s 1874 directory has a full-page advert for “The Conservative Association for the Polling District of Croydon”, listing “S. L. Rymer, Esq., London Road, Croydon” as treasurer. Information about his vice-presidency of the Croydon Conservative Association, presidency of the Croydon Literary and Scientific Institution, and position with the Whitgift Foundation is taken from an article on page 9 of the 11 March 1909 Croydon Chronicle; this states that he became a Governor of the Whitgift Foundation in 1888 and Chairman in 1892. Information on his honorary secretary role is taken from Old & New Croydon Illustrated. Information on his founding of the Croydon Guardian is taken from an article in the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser.

- Most of this information is taken from articles in the 13 March 1909 Croydon Advertiser (page 6 et al.), the 11 March 1909 Croydon Chronicle (page 9), and the 13 March 1909 Croydon Guardian (page 2). (Quotation is from the Croydon Advertiser.) These articles also make it clear that the office of alderman was one that was regularly re-elected, and that Samuel successfully retained his position every time. The Croydon Advertiser gives 7am as his time of death, while the Croydon Chronicle claims 5:30am. His death was also reported in several other newspapers, including the 8 March 1909 London Daily News (page 8, column 6), the 13 March 1909 Shoreditch Observer (page 7, column 1), and the 9 April 1909 Surrey Mirror (page 5, column 2) (all links go to the British Newspaper Archive, which requires a subscription to view). See photo in main article for gravestone including Elizabeth’s name.

- To avoid tedium, I have not listed every documented inhabitant of the nine houses in the main article, but I give their names and rough dates here for the benefit of those websearching: William Edward Acraman (1850s), Mrs Ades (1890s), Miss Allsop (1910s), William Arnold (1880s), John Baines (1860s), William F Blockey (1870s), William Frederick Burnett (1900s), Charles Christie (1880s), George Acton Davis (1870s), John G Deacon (1900s), Thomas Henry Ebbutt (1880s), John Edward/Edwards (1850s), George Ellis (1850s), Charles S Evans (1860s), Mrs H M Feist (1890s), Joseph John Fletcher (1900s), Henry Franklin (1880s), Albert Freeman (1870s), William Froom (1860s), Mrs Garraway (1860s), Charles Robert Good (1880s), Miss L M Gunn (1890s), Thomas W Gunn (1890s), Frederick Hanscombe (1900s), Allen Edgar Hawkins (1900s), William Codner/Codnor Henley (1860s), Robert Hill (1920s), Frederick Samuel Hopkins (1860s), Frederick Horne (1850s), William Henry Horniman (1860s), Henry Horsley (1910s), Michael Jones (1900s), William Burbidge Lanfear (1860s), Rev C Large (1920s), B E Laurence (1900s), Miss Lennox (1880s), Minnie Levine (1950s), Thomas Lewis (1860s), Geoffrey F Linn (1950s), J C Martin (1890s), William Randall Martin (1880s), Henry Tuke Mennell (1860s), Alfred Le Mercier (1870s), W D Merritt (1880s), Miss Midgley (1900s), A F Mieville/Meirille (1870s), Thomas Benjamin Muggeridge (1850s), P F O’Hagan (1890s), Robert Overbury (1870s), John Henry Paine (1900s), Miss Pearce (1880s), Miss Porterfield (1880s), John and/or Joseph Roberts (1870s), Samuel Lee Rymer (1870s), Louis Schnabel (1900s), Alexander Scott (1870s), Henry Scott (1850s), William Scott (1840s), Samuel Selmes (1850s), Miss Sherrin (1890s), Joseph H Shorthouse (1870s), Robert Shotten (1850s), William Shrubsole/Shrubsall (1920s), Alice M Siney (1950s), Herbert S Skeats (1850s), John Slaughter (1880s), Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith (1900s), Hector Strait/Straith/Straigth/Straighth (1840s), E & J Stubbings (1890s), Mrs Teal/Teale/Tealey (1860s), Julius Thompson (1850s), Charles Upton (1880s), Thomas George Lowe West (1860s), and M A Wolstenholme (1920s). Most of these names are from street directories and/or rate books. Hector Strait (as “Major Strait”) and William Scott are listed as occupants of John Blake’s houses in the 1844 Tithe Award. The multiple spellings of the former’s surname come from different rate books.

- Information taken from Ward’s directories, with additional information on Miss Feist’s class from an advert in the 14 January 1893 Croydon Guardian, reproduced here.

- Ward’s directories list the southernmost of the

nine houses (69 London Road in contemporary numbering) as unoccupied

from 1901 to 1913 inclusive, and its neighbour (71 in contemporary

numbering) as unoccupied from 1898 to 1913 inclusive. (Note that the

data for these directories were generally finalised in November or

December of the previous year.)

The two houses at 69 and 71 London Road were a semi-detached pair (see 1868 map in main article). Note that I state they were converted into the Co-op store, not demolished and replaced. My main reason for thinking this is an aerial photo in the General Hospital collection at the Museum of Croydon (ref PH 97 22.540), labelled “c.1924”, which shows the Co-op from above and behind. A tall rectangular protrusion is visible right in the middle of the building, of a similar footprint and location to the still-remaining semi-detached pair to the north, symmetrical about a central axis, and with, like its neighbours, smaller windows on the very top floor suggesting servants’ quarters. A false façade at the front of the building conceals this from street view. It looks very much as though the new store was essentially built around the existing houses, engulfing them in the process.

- An advertisement in the Croydon Times George V Silver Jubilee Supplement, published on 6 June 1935, states that “sixteen enthusiasts started the Society in Church Street” in 1887. The quotation in the main article is also taken from this advertisement. Ron Roffey’s The Co‑operative Way also gives the date of 1887 for the Society’s establishment, and states that its headquarters were at 85 Chesham Road, South Croydon (Chapter 2, pages 21–22).

- Croydon Advertiser, 18 July 1914, page 12, describing a speech by the Society’s President, Mr C Bailey.

- The above-cited 1935 Croydon Times advert states that “1907 saw the opening of new premises at London Road”. Corroborating this, Ward’s directories list the Croydon Co‑operative Society Ltd at 30 London Road (later renumbered to 64) from 1908 to 1914 inclusive. Other information taken from Croydon Co‑operative Society Minute Books (Museum of Croydon ref Cr/6); committee meeting minutes dated 25 April.

- Name of architect taken from an article on page 8 of the 18 July 1914 Croydon Guardian. Frank Bethell was involved before completion of the purchase; he’s mentioned in the 20 March 1913 Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 20 March 1913 as having provided “sketches” for the new premises and as the person who would be instructed to make an offer for the land. Other information is taken from Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 13 June, 27 June, 30 August, 5 September, and 25 September. None of the firms invited to tender were based in Croydon; the closest geographically was Bowyer & Sons of Upper Norwood (which itself seems to have dropped out by the time of opening the tenders).

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 24 September and 14 November 1913.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 13 February (main quotation) and 6 February (clarifying sub-quotation) 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 13 February 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 6 March 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society Special General Meeting minutes dated 18 March 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society quarterly meeting minutes dated 15 April and committee meeting minutes dated 17 April.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 24 April, 1 May, and 12 June 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 22 May 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 19 June 1914.

- Croydon Co‑operative Society committee meeting minutes dated 19 June 1914.

- Croydon Advertiser, 18 July 1914, page 12. A very similar article appears on page 8 of the Croydon Guardian of the same date.

- Number of members in 1914, and quotation from President, taken from “Co‑operative Society”, Croydon Advertiser, 18 July 1914, page 12. The July 1914 London phone book lists branches at 35 The Pavement and 157 Portland Road, as well as the main premises at 69–71 London Road. Numbers of members and branches in 1916 are taken from the 1916 Co‑operative Directory (information provided by the National Co‑operative Archive).

- The April 1920 London phone book lists 69 London Road as the “Registered Office” of the SSCS, and the 1922 Co‑operative Directory lists 69–71 as its “Central Premises”. All other information is taken from The Co‑operative Way, Chapter 2, page 20. This latter source also records previous mergers with the Caterham Society in 1906, the Epsom Society in 1916, and the Sutton (Surrey) Society at an unspecified date; no information is given about any change of name of the Croydon Society in connection with this, and Ward’s directories continue to use the name “Croydon Co‑operative Society” up to the point of the merger forming the South Suburban Co‑operative Society.

- Ward’s directories for 1920, 1921, and 1922 list Dr Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith at number 73 and “Co-op Warehouse” at number 75. The 1923 edition has the SSCS at numbers 69–75 (and other occupants at numbers 77 and up).

The process of this later expansion is somewhat unclear, and the 1927 renumbering of London Road, which happened around the same time, muddies the waters further. Ward’s directories suggest that the expansion may have happened in stages, with the first semi-detached pair being taken over by 1927 and the third house joining them a couple of years later, but due to the discontinuity in numbering I can’t be certain. The Museum of Croydon has an aerial photo taken on 25 June 1927 (ref PH/97 22.561, in the General Hospital collection), but unfortunately it only shows the southern part of the building. This photo does however suggest that the early-1920s expansion happened in the same way as the c.1914 conversion, with the existing houses being converted rather than demolished, as there are roof voids with what look suspiciously like the old house roofs within them.

What does seem clear, however, is the situation as of 1933. The 1932 Ordnance Survey map reproduced here clearly shows the footprint of the store at that time, and an advertisement in the 10 June 1933 Croydon Advertiser, found in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon, describes the London Road store as “the new Central Stores of the Society”. The Co‑operative Way also mentions a “more complex multi-floor” store being built at Croydon around 1932 (page 66). Ward’s directories make no mention of any “building” during this time, possibly suggesting that all this was conversion and extension rather than demolition and rebuilding; however, there was no edition of these directories published in 1931, which leaves a two-year gap in which building work could have taken place.

- Figures are taken from the above-cited 1935 Croydon Times advert, and relate to the “year ended March, 1935”.

- Image reproduced courtesy of the Croydon Advertiser and the British Library. For more information on the bread rationing of the 1940s, see Christopher Knowles’ blog series on the subject.

- A planning application for “4 shops with maisonettes over (91–97)” was granted on 27 January 1939 and completed by 31 December 1941 (viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices, ref 39/23). Another planning application for “new shopfronts for greengrocery, junior miss, special baby linen and pharmacy” for “the South Suburban Co‑operative Society Ltd” was granted on 20 January 1950 and completed at some unknown later date (ref 50/33).

The Co‑operative Way states on page 112 that “It was during 1952 that a freehold site adjacent to the Society’s central premises in London Road, Croydon, was purchased, expanding a total frontage to 400 feet on the main road with over 270 feet on the return in Montague Road. This acquisition enabled shopping to be developed, the grocery warehouse enlarged and an additional exit provided at the rear of the site.” The distance of 400 feet (122 metres) matches well with the distance from Montague Road to the southern edge of the Lidl carpark as measured on OpenStreetMap today.

I haven’t been able to corroborate this from primary sources; I looked through the 1952 entries in the SSCS Feb 1952-Apr 1953 minute book (ref SSCS/18 at the Museum of Croydon), checking the index notes in the margins and looking properly at sections which seemed likely to relate to land purchase, but didn’t find anything relating to purchase of this final strip of land. However, I might have missed something, and this volume does omit January.

A planning application deposited on 5 October 1953 includes a plan which shows the two houses (numbers 113 and 115) still in place, while the 1954 Ordnance Survey map (viewable online via the National Library of Scotland) shows only number 115 remaining. Oddly, the former plan has 113 shaded, which according to the key indicated “premises not used by or owned by Society”; however, the Society was granted planning permission for “Offices, Covered Yard & Warehouse at rear” at this address on 23 August 1950. It’s possible that the planning permission was gained in advance of the purchase, and that part of the purchase was delayed for some reason. Regarding the state of number 115 in 1954, a letter dated 13 July from Poster Services Ltd to the Borough Engineer, included in the records of planning application A719, describes a proposal to erect a fence and advertising sign “on the splay at the corner of London Road and Montague Road [...] to the house in Montague Road” that would “cover out [sic] the untidy space in front of the derelict house”.

- Planning application references include 67/1832/20/1095, 69/20/796, and 69/20/1128. Notably, not all of these were for development by the Co-op itself; 67/1832/20/1095, which was withdrawn, was submitted by Firestone Rubber Co for use as “Tyre & Auto Services Ltd”.

- Address and extent assessed from the 1974 Ordnance Survey map. It looks possible that the remainder of the land south of Montague Road (i.e. the previous site of number 115) was used for vehicle access to the rear of the store.

- Via email, 13 December 2012. As well as the departments Terry mentions, at some point there was also a music department, according to commenters on a Bygone Croydon thread.

- Via email, 12 August 2016. Dave got in touch after reading this article to mention that he remembers things differently from Terry, and also to point out that the Bygone Croydon comment thread cited in the previous footnote includes several mentions of the “whizzy things” used to transport money around the shop. Dave does however note that “The Co-op may have had a vacuum tube system later, as the Croydon Advertiser had a Lamson tube system installed in their Brighton Road premises in the late 1960’s for sending advertisement and editorial copy from the offices at the front of the building to the production department at the rear.”

- Talking of Croydon: Shops and Shopping 1920–1992 is available under shelfmark S70 (658.8) JOH at the Museum of Croydon.

- The Co‑operative Way states on page 141 that as of July 1984 the Society “had been incurring losses (before surplus on the sale of assets) at the rate of £3.7 million per annum”. Conversion to 2015 prices made with 1983 as base year. Management Committee report as quoted on page 122 of The Co‑operative Way.

- Information taken from pages 122–123 of The Co‑operative Way; Management Committee report as quoted on page 123.

- The Co‑operative Way, pages 110 (RACS merger), 123 (SSCS merger), and 142 (admin offices consolidation). This source states (page 142) that the “management and administration of both Societies were integrated, and from June 1985 were based at Woolwich.” However, an archives accession note at the Museum of Croydon (accession number: 390) states that “South Suburban Branch H.Q. closed Friday 17th May 1985, moved to 1B Blackhorse Lane, Addiscombe, Croydon CR0 6RT” (an address that no longer seems to exist). It’s possible that the move to Blackhorse Lane was a very temporary one while the Woolwich offices were sorted out.

- As noted in the previous footnote, the “Branch H.Q.” closed on 17 May 1985, though it’s not clear whether this refers to just the admin offices. In any case, the March 1985 Goad plan shows the site as “(South Suburban Co Operative Society) Vacant”. Size of car park taken from the June 1991 Goad plan, which shows the work as being complete.

- This image used to be (but is no longer) displayed on Brian’s Flickr photostream, where he commented saying “The Routemaster on route 109 means this photo is proably [sic] taken in late 1986/early 1987.”

- Goad plans show the new store as under construction in March 1990, “Co-op Superstore” from June 1991 to June 1998 inclusive, and “Lidl Supermarket” from September 1999 onwards. A Co‑operative Wholesale Society superstore is listed at 99 London Road in the February 1992 Croydon phone book (and absent from the 1990 edition). Sophie Lambert-Russell of the Lidl UK Press Office confirmed to me that Lidl opened in 1999 (via email, 6 July 2016).

Origin of Lidl, date of first retail store, current number of stores, and quotation taken from the History page on the Lidl UK website (accessed 1 July 2016 — note that the wording I quoted has changed slightly since).

According to a brief article on page 8 of the 8 October 1994 issue of The Grocer, Lidl was due to open its first UK stores — “as many as a dozen” of them — on 17 November of that year. The report also stated that “Planning applications are being submitted as quickly as one a week and in the last two alone it has put in for branches in Newquay, Exeter and Shrewsbury.”

- “Lidl seeks staff”, The Grocer, 15 October 1994, page 10. From personal observation, Lidl still uses cost-cutting practices today. One example is that it only puts just enough staff on checkouts, so queues develop even at off-peak times, and the checkout areas are physically very small, discouraging customers from spending too much time on bagging. Another example is that products are not removed from their transport cartons before being placed on shelves; see photo and another photo.

- A photo of the temporary store is available on Flickr, dated 3 December 2016. Reopening date and detail about Mayor of Croydon taken from “Riot-hit store is back in business”, Croydon Advertiser, 11 April 2012, page 6. It may have opened slightly before this, as a photo by the same photographer dated 24 March 2012 shows a banner reading “Your new & improved store now open”.

- Planning application ref 99/475/P; unfortunately I haven’t been able to view this record in full, so all I have is the information on the property’s index card, which gives a date of 11 August 1999 for the original application. Fitness First is listed in the January 2001 Croydon phone book, and further confirmation that it was open by 2 February 2001 comes from the Internet Archive snapshot of the Fitness First website on that date, which includes Croydon in the dropdown options for finding your nearest branch, and which states on its “Members Benefits” page that “you can enjoy membership privileges to over 130 Fitness First clubs worldwide at no additional cost”.

- Details of facilities taken from two leaflets found in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon. One is undated, and lists prices for hairdressing services ranging from £10 for a wash and blow dry to £300 for “Cinderella extensions”, all provided by a company called Helena McRae (which, at the time of writing, still has a presence in Croydon at 78 High Street). The other has “April ’01” handwritten on it, and describes all the other services mentioned as well as advertising an offer of 100% off the usual joining fee of £100, expiring 7 May 2001.

- Everything in this paragraph is from personal observation.

- Date of Employment Tribunal move and its previous location both supplied by Michele Gayle at the South London Employment Tribunal, who also confirmed that the offices were empty before the Tribunal moved in, and that it is the sole occupant of the offices today (via email, 4 July 2016).