Stonemead House at 95 London Road sits back from the road, beyond the entrance to the Lidl carpark. Built in the early 1990s, it occupies a site that was previously part of the grounds of North End Lodge, a grand private residence that later became a school before being demolished in the late 1930s.

1840s–1870s: The Squires at North End Lodge

The land on which North End Lodge was built was originally part of an area of common land known as Parsons Mead. Following the Parsons Mead Enclosure Act of 1823, this common land came under the ownership of the Caldcleugh family, who shortly afterwards split it up and auctioned it off in lots on 23 May 1835.[1]

Lot 9, with a frontage of around 25 metres and an area of just under 1800 square metres, was one of several plots bought by Charles Crowley.[2] By early 1843, Charles had built a house on this land, and on 30 January of that year he leased both house and land to John Squire for a period of 99 years, with the rent fixed at £30 per year [£3438 in 2015 prices].[3]

There is some confusion about the ownership of the land over the next few years. The 1844 Tithe Award lists Lot 9 as being both owned and occupied by William Squires [sic], and Lot 42 as being “Building ground” owned and occupied by John Budgen. However, the 1843 lease would have still been in effect at this time. It’s possible that John had transferred the lease to William, and that William was then listed as the owner simply because the lease was such a long one.

It’s unclear, too, what role William Squire really played. He appears to have been John’s brother,[4] but as noted above, the lease was in John’s name. Moreover, by the time of the 1851 census, John is listed as head of the household and William is absent.

Also part of the household in 1851 were John’s sisters Frances (known as Fanny) and Louisa. While at least part of John’s income would have come from his profession as an engineer, he likely had investment income too. His sisters certainly had such income, and this included a sufficient surplus that they were able to build and maintain a girls’ school known as the Mead School, situated “at the lower end of Parsons Mead”.[5]

While the Squires only ever had the leasehold of North End Lodge and the grounds behind it, at some point during their tenure they acquired the freehold of the land to the south and expanded their gardens into this. Although still smaller than the Oakfield Estate across the road, the eventual boundaries of their estate took in a total of over 6,600 square metres.[6]

John, Fanny, and Louisa continued to live together at North End Lodge until John’s death on 20 October 1872. The siblings were all Quakers, and John was buried at the Friends Meeting House on Park Lane. Fanny and Louisa remained on London Road for a short while after John died, but moved to Dorking by mid-1876.[7]

1870s–1880s: Joseph Steele and Thomas Tarleton Hodgson

The next occupant of North End Lodge was Joseph Steele, son of the Squires’ sister Emma.[8] Joseph was a surgeon dentist working in partnership with another dentist, Samuel Lee Rymer, who lived just a few doors along from him in a semi-detached house near the junction with Montague Road. According to an article in the August 1876 Monthly Review of Dental Surgery, this partnership “proved of great advantage, as the health of neither being very good they were able to relieve each other in the arduous work of a large practice.”[9]

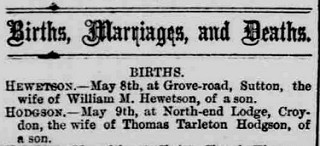

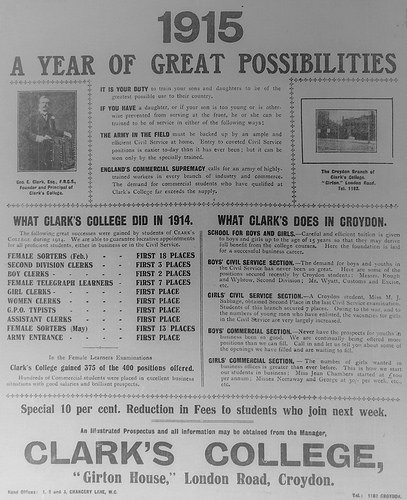

Joseph was in residence by mid-1876, but left again around 1882. His replacement was Thomas Tarleton Hodgson, in place by 1883 and gone again by 1890. Little information survives about Thomas, aside from the fact that his wife, Lucy Laura Hodgson, died very soon after their arrival on London Road, possibly of complications arising from childbirth.[10]

1890s: George Newman renovates North End Lodge

Next to arrive — and the final person to use North End Lodge solely as a private residence — was George Newman, chairman of a building and contracting company. George was in his early 40s when he arrived on London Road in late 1890, having moved here from Farnley House in South Norwood along with his wife Ellen and their eleven children.[11]

North End Lodge, despite its three floors, seven bedrooms, dining room, library, drawing room, breakfast room, and conservatory, was clearly not grand enough for George’s liking, as he set his company, George Newman & Co, to conducting “considerable works [...], incurring a large outlay, in altering and adapting his private residence”. He even got the company to pay for this; on 24 April 1891, the board of directors passed a resolution noting that:[12]

The Chairman [...] suggested that as such alterations were considered by him necessary to maintain the social position held by him as chairman of [...the] company, and having regard to the many important operations now being conducted by this company entailing upon him constant and assiduous attention, that it would not be unreasonable for the expenditure above referred to to be treated as a proper expenditure of the company for its purposes; thereupon it was unanimously [r]esolved that the cost of the works at North End-lodge, Croydon, be debited to the separate account of the Chairman, and liquidated by a credit entry authorised by this resolution.

The fact that all except one of the company directors at this time were Newmans may have had something to do with their determination that this was “not unreasonable”.[13] In any case, just a couple of years later, this and other transactions of the company were exposed to public view with the breaking of the Balfour scandal.

1892–1893: The Balfour scandal, and George Newman’s downfall

Born in Marylebone in 1843, Jabez Spencer Balfour later spent several years working as a parliamentary agent before entering the business world as director of several interconnected property development companies. By the end of the 1870s, his Liberator Building Society was the largest building society in the country.

In 1869, he moved from Reigate to Croydon, initially choosing the “relatively modest” Wilton Lodge on London Road but upgrading himself around the end of 1879 to the “handsome and ancient mansion” known as Wellesley House, a couple of hundred metres to the southeast of West Croydon Station. He was elected to the local school board in 1874, served as Croydon’s first mayor in 1883–4, and was twice elected to Parliament; first in 1880 as MP for Tamworth, and again in 1889 for Burnley.[14]

Despite his outward prosperity, however, Jabez’s expertise lay not in sound business decisions but in “misleading statements, false accounting, and petty fraud”.[15] Warnings began to surface in summer 1889, when the Financial Times published a report on one of Jabez’s companies, the London, Edinburgh and Glasgow Assurance Company, finding its assets “ludicrously overvalued” and its principal skill that of “cooking its books and inventing surpluses where only losses existed.” The report concluded that readers should “give the concern a wide berth, and [...] be on their guard against any companies of which Mr Jabez Spencer Balfour [...] is a director”.[16]

Although Jabez fought back against these accusations, it was only a matter of time before the Financial Times assessment was proved accurate not only for this particular company but for every pie in which Jabez had a finger. With heavy overlaps between boards of directors, it was easy to transfer assets from one company to another, inflating their value each time and thus increasing the wealth — at least on paper — of the companies. His bank, the London and General, was also generous in approving loans to these companies. This was not, however, a sustainable strategy, and by autumn 1892, all had unravelled. The London and General collapsed, the debts of the other companies became public, and Jabez fled the country.[17]

George Newman played a small but significant part in all this. As a well-to-do Croydon resident, he likely knew Jabez socially, but the two men also had business dealings. George acted as a surveyor and valuer for Jabez’s Lands Allotment Company,[18] and in 1885 George Newman & Co became part of the Balfour Group.[19] At the collapse, George’s company had unsecured liabilities amounting to £66,425 [£7.7m in 2015 prices], plus the shareholders’ paid-up capital of £25,000 [£2.9m in 2015 prices]. The Official Receiver deemed all the company’s assets valueless.[20]

In January 1893, George Newman was charged under the Larceny Act as having “caused to be made certain false entries in a ledger” in connection with “conspiring with [Henry Granville] Wright to defraud the Liberator Building Society of [£]2,500 [£290,000 in 2015 prices]”.[21] Two months later, on 25 March 1893, he was found guilty and sentenced at the Old Bailey to five years’ penal servitude for fraud.[22] His “furniture and household effects” were sold at auction on 8 May, and North End Lodge itself, along with its land, was sold in the same way a week later.[23]

1893–1898: Purchase by the Methodists, and Robert Hawe’s school

Although North End Lodge had been marketed in the 1893 sale as a “commodious detached family residence”, it was purchased not by a family but by “a syndicate of gentlemen who intend[ed] to erect a Wesleyan Chapel on a portion of the ground”.[24] The church was built on the southern half of the grounds, and formally opened on 6 September 1900 after a year of building work which itself was preceded by several years of fundraising.[25]

The northern half of the grounds, including North End Lodge itself, was rented out to a private school which had previously been situated just down the road at numbers 63–65. The headmaster was Robert Hawe, and the school was known as College House School.[26] Advertising in the Surrey Mirror of 17 May 1895, it boasted “electric light throughout” as well as a “[p]rivate field of 14 acres, for games, within five minutes’ walk from the School”.[27] George MacDonald Davies, who attended the school in 1895, recalled both of these features in a later essay:[28]

The grounds sloped down to Parsons Mead and the playing field was at the barracks in Mitcham Road. Every Wednesday the head master started up a gas engine in the basement to drive a dynamo, and the electricity was stored in batteries that lined the walls of the room.

College House School remained here for only a handful of years, before moving to Wellesley Road around 1898.[29]

1900s: The Misses Stoneman’s ladies’ school

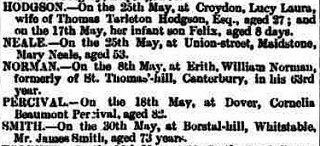

The next occupants used the premises as a combination of private home and private school. William Greek Stoneman, his wife Sarah, and their adult daughters Mary, Ellen, and Lilian moved here from 44 Kidderminster Road by January 1898. William was in his 70s and living “on [his] own means”, while Lilian and Mary, unmarried and in their 30s and 40s respectively, used part of the property as a private school for girls.[30]

This school, known as Girton, operated as a boarding and day school including a “preparatory class for little girls under 8 years of age”, with “Preparation for Public Examination” offered “if desired”.[31] The 1901 census records just four boarders at the school, aged from 15 to 17, as well as a 22-year-old governess, two maids, and a cook.[32]

William died on 20 February 1908, leaving effects of £9512.1s.6d (just over £1m in 2015 prices). Mary and Lilian’s school continued on London Road for a short while after this, but by 1911 Mary had returned to 44 Kidderminster Road along with her mother, and Lilian was running a school in South Croydon — this time without the help of her sister.[33]

1910s–1960s: Clark’s College

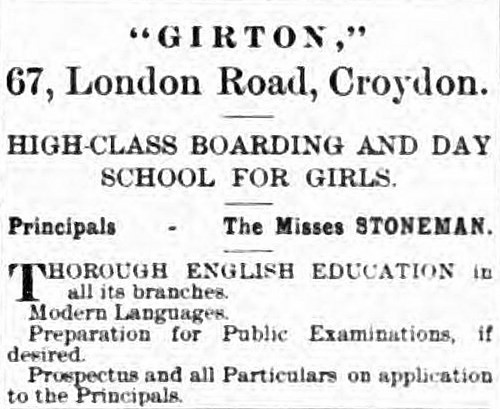

Girton’s replacement was another school, but one which was rather more well-known and which would remain on London Road significantly longer. Clark’s College was founded in 1880 by ex-civil servant George E Clark in order to prepare students for Civil Service examinations. By the time its Croydon branch opened at 1 Addiscombe Road in 1909, it already had at least eight other branches around Greater London in addition to its main premises on Chancery Lane.[34]

By mid-1910 it had opened a girls’ school at Girton House (which, apparently, was now the name of the building previously known as North End Lodge), and by early 1913 it had transferred the entirety of its Croydon operations to London Road.[35]

1910s–1920s: A new school building

The grounds attached to the building, previously stretching back to Parsons Mead, had by this point been somewhat truncated, and a block of four houses built on the Parsons Mead frontage.[36] However, there was still room behind the main school not only for a playground, but also for a newly constructed building to house a junior school for children aged up to 14. Built toward the Parsons Mead end of the playground some time between 1913 and 1924, this had three classrooms separated “by folding partitions which when thrown open enable[d] the whole building to be used as a hall, at one end of which a stage [...was] erected for dramatic and other performances.”[37]

When inspected by the County Borough of Croydon’s Education Committee in December 1924, the school had 271 pupils, both male and female, aged from 5 upwards; 50 of these attended the junior school, 176 attended the commercial section in the old North End Lodge premises, and 45 attended commercial evening classes.

The report of this inspection, which was primarily concerned with the junior school pupils, notes that these pupils were instructed in “Scripture, Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Composition, Spelling, Dictation, History, Geography, Nature Studies, and a little French and Geometry”. The inspector also considered it notable that there was “no provision for Manual Work”, and that “a somewhat novel use [...was] made of the public newspaper” in the dictation exercises.[38]

1930s: The end of North End Lodge

Further construction work took place in 1938, with the junior school being extended and enlarged to two storeys in order to house the entirety of the school in a single building. A short article in the July 1938 Clark’s College magazine described this:[39]

We are looking forward to our new building, and are watching it rise on part of the large playground at the back of our present premises. It was noticed recently that the school drawing class had appropriated a workman’s pick and shovel as a study for free-hand drawing!

Work was complete by early October, and by the end of the month all the students had moved over to the new premises, where they “appreciate[d] the convenience and general compactness of the new arrangements.”[40]

This also signalled the end of North End Lodge, which was demolished after just under a century of life and replaced by four shops fronting on London Road. These shops were very likely both built and occupied by the South Suburban Co-operative Society, which by this point had a huge department store on the neighbouring site to the north.[41]

The college itself remained in its new building behind these shops until the mid-1960s, throughout which time it continued to offer both general education and commercial education. By August 1965, however, it had departed Croydon for good.[42]

1960s–1980s: The General Post Office

In May 1964, Clark’s College Ltd was granted planning permission for a change of use to offices, and by August 1965 the old school building was in use by the General Post Office (GPO). The latter remained here until mid-1987, meanwhile undergoing a change of name first to Post Office Telecommunications and then to British Telecommunications.[43]

1990s–present: Stonemead House

By mid-1985, the Co-op store next to the old GPO building had closed down, and plans had been made for a complete demolition and rebuilding. This demolition included the four shops which had been constructed in front of the latter building, leaving it visible from London Road once more. It was not reoccupied, however, and by mid-1992 was in a “derelict” state.[44]

It’s unclear precisely when this building was demolished and replaced by Stonemead House, and it's also unclear who performed the rebuilding. At least three planning applications for a new office building were granted in the early 1990s, to at least two different developers.[45]

In addition, the present form of Stonemead House is possibly not its original form. At least one of the abovementioned planning applications stated an intention to build two separate three-storey buildings and connect them with a walkway; while another application, granted a decade later, requested permission to construct a three-storey glazed extension which could well correspond to the central portion of today’s building.[46] In any case, although somewhat removed in both position and style from the original North End Lodge, Stonemead House remains as a not unattractive building which adds a little interest to the southern end of the Lidl carpark.

Thanks to: Brian Simmons; the British Newspaper Archive; Croydon Quakers; Girton College Archive; Homerton College Archive; Newham College Archive; Stiles Harold Williams; Stuart Williams; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-reader Alice. Census data, FreeBMD indexes, and London phone books consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

- See my article on 21 London Road, part 1 for more information on the Parsons Mead enclosure and the sale by the Caldcleughs.

The Museum of Croydon has a copy of the sales particulars for the 1835 sale with handwritten notations showing who purchased which lots (ref BA268); this shows that “C. Crowley” bought Lots 9, 16, 17, and 42. The 1844 Tithe Award gives Mr Crowley’s full name as Charles Sedgefield [sic] Crowley (cross-referencing being possible as he still owned Lots 16 and 17 at that point), while the conditions of sale included in particulars for a sale of the North End Lodge grounds in 1889 (ref HR775 at the Museum of Croydon) refer to an 1843 lease between John Squire and Charles Sedgfield [sic] Crowley.

Regarding the size of Lot 9, the 1835 sales plan shows that this had a London Road frontage of 80 feet 6 inches and ran back 238 feet on the south side and 244 feet on the north side. Handwritten figures of “Rod” are written along all the plots, with lot 9 having “71”. A rod was 16.5 feet, so 71 square rods corresponds to 19,325.75 square feet; this is right in between what one would get from naïve area calculations assuming a perfectly rectangular plot and using 238 feet and 244 feet respectively as the lengths of the longer sides, and similar calculations for other plots also work out correspondingly, so these figures must refer to areas in square rods. 19,325.75 square feet is 1795.79 square metres.

The conditions of sale included in particulars for a sale of the North End Lodge grounds in 1889 (ref HR775 at the Museum of Croydon) state that “The title as to Lot 1 [which consisted of Lots 9 and 42 from the 1835 sale, plus North End Lodge] shall commence with the indenture of lease, under which the same is held, dated 30th January, 1843, between Charles Sedgfield [sic] Crowley of the one part, and John Squire of the other part”. The description of Lot 1 includes the statement that “This Lot is held for 99 years, from the 25th day of March, 1843, at a Ground Rent of £30 per annum.” The discrepancy between the dates here is likely because although the lease agreement was made on 30 January, it was not to take effect until 25 March; that is, Lady Day, which for historical reasons was commonly used as a start date for lease periods.

Charles Crowley, incidentally, was Aleister Crowley’s great-uncle. Hampshire County Council’s Fine Art Collection includes a portrait of him which can be viewed on the Art UK website. See Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley (Revised and Expanded Edition) by Richard Kaczynski, pages 8–9 (available online via Google Books) and Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton, pages xvi and xxxv (also available online via Google Books) for more on Charles, including his work with railways. Aside from his unusual middle name, the 1844 Tithe Award offers further confirmation that this was the same Charles Sedgefield Crowley, as it lists a plot of land as being held by Abraham, Charles Sedgefield, and Henry Crowley — three of Aleister Crowley’s grandfather’s brothers.

- Research by Ancestry user NeatbyOne (requires Ancestry account to view) states that John had a brother, William, born on 13 January 1791, though no sources are given for this assertion.

- The 1851 census lists John (unmarried, age 58, engineer), Louisa (unmarried, age 52, “Share Holder &c”), and two servants in residence. Fanny (unmarried, age 54, “Fundholder”) is listed elsewhere, as a visitor in the household of Joseph Neatby in St Mary, Newington, Surrey. However, it seems extremely likely that she actually lived with John and Louisa at this point. Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past: Historical, Monumental, and Geographical (published in 1883) includes on page 101 a biographical note on Maria Merredew, who “was formerly mistress of [...] ‘The Mead School’ [...to which...] many of the present good wives of Croydon owe their education [...and which...] was built at the lower end of Parson’s Mead by the Misses Squire, two maiden ladies of the Society of Friends, who then resided in the London Road, with their brother, in the house now occupied by Mr. Joseph Steele. The school was carried on mainly at the ladies’ expense, though a small school fee was charged to the children.” Maria’s death announcement on the front page of the 3 August 1861 Croydon Chronicle (viewed on microfilm at the Museum of Croydon) states that she ran the school “for nearly eleven years” before being forced to retire “on account of severe illness which [...was...] very painful and long protracted”. The school must therefore have been in existence in 1851, strongly suggesting that Fanny was living with John and Louisa by then. The censuses give Fanny’s name as “Frances Octavia”, but the October 1858 and November 1862 Poor Rate Books give it as “Fanny” (other Poor Rate Books list her simply as “Miss F Squire”).

- The 1889 sales particulars cited above (ref HR775 at the Musum of Croydon) offer the leasehold of the northern half of the property along with the freehold of the southern half, and state that the title of the former begins with Charles Crowley’s 1843 lease to John Squire, while the title of the latter begins with an indenture of conveyance by which Fanny Squire sold the land on 21 April 1874. These particulars also give the total area of the estate as “about 1a. 2r. 22p.”; that is, 1 acre (4,840 square yards), 2 roods (1,210 square yards), and 22 square perches (30.25 square yards), a total of 7,925.5 square yards or 6,626.73 square metres. (See Jo Edkins’ Imperial Weights and Measures website for more information on these units.)

- Date of John Squire’s death and place of his burial are taken from Croydon In The Past page 105. Confirmation that this is the same John Squire, information on the Squires’ Quakerhood, and information on Fanny and Louisa’s move to Dorking all comes from page 101 of the same publication, which mentions “the Misses Squire, two maiden ladies of the Society of Friends, who then resided in the London Road, with their brother, in the house now occupied by Mr. Joseph Steele. [...] the Misses Squire [...] on the death of their brother, removed to Dorking, where they now reside.” The December 1873 Poor Rate Book lists Miss Louisa Squire as still living on London Road, and Ward’s 1874 directory (which according to the preface of the 1876 edition was published “early in 1874”) also lists “Miss Squire”. Ward’s 1876 directory instead lists Joseph Steele; the page on which this listing occurs is in a section dated 17 June 1876.

The GOV.UK “Find A Will” search states that one of the executors of John’s will was his nephew Joseph Steele. Research by Ancestry user NeatbyOne (requires Ancestry account to view) states that Joseph’s mother was John’s sister Emma, though no sources are given for this.

Aside from monetary bequests totalling £3,260, John’s will left his entire estate, “whether freehold or leasehold[,] stocks[,] funds[,] securities for money[,] shares and every other description of property” to Joseph and his cousin Henry Steele to “share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants”. (My transcription of a copy of the will purchased via the abovementioned “Find A Will” search. It should be noted that I’m not 100% certain of my transcription of “Henry”, and I can’t find an appropriate Henry Steele in the 1871 census.) The leasehold on North End Lodge and the northern part of the grounds must have formed part of this. It does however seem possible that it had been Frances who owned the freehold of the southern part of the estate, and that she sold this on to Joseph after her move to Dorking. As shown earlier, Frances certainly sold that part of the land to someone in 1874, and since subsequent sales particulars show the leasehold part and freehold part of the estate being sold together, most likely that someone also owned the leasehold of the other part.

Ward’s directories list Joseph Steele, “L.D.S., R.C.S., Surgeon Dentist (Rymer & Steele)” at 34 London Road (later renumbered to 67 and then 97) from 1876 to 1882 inclusive. Other contemporary directories use the name “North End Lodge” for this address, as does Ward’s from 1884 onwards. It may in fact have been Joseph who gave the house its name, as the earliest contemporary reference I’ve found to it is in Atwood’s 1878 directory, during Joseph’s tenure. Wilkins’ 1876–7 directory actually uses the name “Broad Green Lodge”; although this must be a mistake, as there was a well-established Broad Green Lodge a little further up the road around the site of the modern number 363, this confusion does perhaps suggest that the name of North End Lodge was new.

Samuel Lee Rymer is listed at 41 London Road (later renumbered to 81 and then 111) in directories from Wilkins’ 1872–3 (as S L Rymer) to Ward’s 1880 inclusive. Contemporary maps show that this was three houses south of the junction with Montague Road. Samuel was rather more famous than Joseph; the abovementioned article in the Monthly Review of Dental Surgery (Volume 5, Number 3, August 1876, pages 105–110, viewed online via the Internet Archive) was actually about him, with Joseph mentioned only as an aside. Among his other accomplishments, Samuel was a founding member and president of the British Dental Association, was elected to the Croydon Local Board of Health, and served a term as Mayor of Croydon. (I’ll discuss him further in a future article.)

- See previous footnote for Joseph’s dates at London Road. Ward’s directories list Thomas Tarleton Hodgson from 1884 to 1889 inclusive; he also appears in Purnell’s 1882 directory. Thomas was definitely in residence by May 1883, as the 12 May 1883 Surrey Mirror records his wife as having given birth to a son on “May 9th, at North-end Lodge, Croydon” (front page, first column, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). Ward’s 1890 directory lists North End Lodge as unoccupied. From the timing, it seems possible that Thomas was in fact the vendor of the previously-cited 1889 sale.

- Ward’s directories list George Newman at North End Lodge in 1891, 1892, and 1893; the first of these would have been finalised in late 1890. The 1891 census lists George Newman, 42, auctioneer and surveyor; his wife Ellen, also 42; and eleven children ranging in age from 10 months to 23 years, including Frederick C (16, surveyor’s clerk), George (20, land and building surveyor), and John H (23, builder and contractor). Other information comes from an article in the 20 May 1893 Croydon Advertiser (“Another Balfour Smash”, page 8), which states that George Newman & Co was “incorporated in January, 1886, for the purpose of acquiring and carrying on the business of Mr. George Newman, a builder and contractor”. The article also states that George was chairman and managing director at the time of the company’s formation, and that he was still chairman on 24 April 1891, when a resolution was passed agreeing that the company would pay for the works conducted on North End Lodge “during the last six months”, and would also buy from him the freehold of his previous residence: Farnley House, South Norwood. Another article in the same edition confirms that George remained chairman as of May 1983 (“The Sale of North End Lodge”, Croydon Advertiser, 20 May 1893, page 8).

- Details of North End Lodge are taken from the previously-cited 1889 sales particulars. Quotations are from “Another Balfour Smash”, Croydon Advertiser, 20 May 1893, page 8.

- “Another Balfour Smash” states that the first directors of the company were George, his brother William, and H G Wright, and later appointments were G Butterfield (who resigned in August 1886), C Newman, J H Newman (probably George’s oldest son, John), D Newman, and G Newman, junior (also probably George’s son).

- Information on moves from Reigate to Wilton Lodge and then to Wellesley House is taken from Jabez: The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Rogue by David McKie, 1st edition, 2004, Atlantic Books, Chapter 3, pages 29 and 35. The quotations regarding his houses also come from here; the first is quoting the author while the second is itself quoted in the book (from an unidentified source). Ward’s 1876 directory backs this up, listing J Spencer Balfour at Wilton Lodge (also numbered as 85 Thornton Heath, which was renumbered to 254 London Road in 1890 and again to 468 in 1927). Wilton Lodge has since been demolished, but I’ll discuss it in more detail in a future article. Wellesley House is shown on the 1896 Town Plans as being on the west side of Wellesley Road, just to the south of the junction with Poplar Walk. Measuring this distance on a modern map (OpenStreetMap data via uMap) gives around 250 metres as the crow flies. All other information in this paragraph and the previous one is taken from Duncan Bythell, “Balfour, Jabez Spencer (1843–1916)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed 30 April 2016).

- Quotation taken from the above-cited Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article.

- Jabez, Chapter 7, pages 88–89. The first two quotations are of the book text, and the third is of the Financial Times article. Unfortunately the author doesn’t give an exact citation for this article, so I haven’t been able to view it myself.

- Jabez, Chapter 8. A further account of the Balfour Group’s dealings, and the subsequent trials and convictions, can be found in Boardroom Scandal: The Criminalization of Company Fraud in Nineteenth-Century Britain by James Taylor, 1st edition, 2013, Oxford University Press, Chapter 9, pages 223–233.

- Jabez, Chapter 8, page 101.

- Jabez, Chapter 2, page 18.

- “The Balfour Crash”, London Daily News, 28 March 1893, page 9, column 5 (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). Price conversions made with 1893 as base year (see acknowledgements for details).

- “The Liberator Society. Another Defendant.”, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 29 January 1893, page 4, column 2, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription).

- Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 30 April 2016), March 1893, trial of Henry Granville Wright and George Newman (t18930306-254).

- “Sale at North End Lodge”, Croydon Advertiser, 13 May 1983, page 8; and “The Sale of North End Lodge”, Croydon Advertiser, 20 May 1983, page 8. I haven’t been able to find out what happened to Ellen and the children when George went to prison. However, the 1901 census shows George, Ellen, and six of the children living at 13 Jerningham Road, Deptford, with George again working as a builder and surveyor.

- First quotation taken from particulars for the sale of North End Lodge and its grounds on 15 May 1893 (ref BA277 at the Museum of Croydon); second quotation from “The Sale of North End Lodge”, Croydon Advertiser, 20 May 1983, page 8.

- See my article on West Croydon Methodist Church for more information.

- Name of headmaster and school taken from the full version of the advert in Ward’s 1894 directory, part of which is reproduced above. Both can also be seen in the 14 January 1893 Croydon Guardian advert reproduced in my article on 63 London Road.

- Advertisement in the Surrey Mirror, 17 May 1895, front page, column 6, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive (requires subscription). A comparison of the 1889 and 1893 sales particulars cited earlier suggests that the electric lighting was installed by George Newman.

- “In Living Memory” by George MacDonald Davies, in Croydon: The Story of a Hundred Years, edited by John B Gent, 5th edition, 1979, CNHSS, p8.

- Ward’s directories list Robert Hawe’s school at 67 London Road (later renumbered to 97) from 1894 to 1898 inclusive, and at 68 Wellesley Road from 1899 onwards.

- An advert in the 1 January 1898 Croydon Advertiser (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription) states that “The Misses Stoneman having secured the commodious premises occupied by Mr. Robt. Hawe, Int. B.A. (who is removing to Wellesley Road), will open the same as a High-class Boarding and Day School for Girls. The Misses Stoneman will be at Home on and after January 6th, 1898, previous to which date particulars can be obtained and premises viewed on application at 44, Kidderminster Road.” This suggests 6 January 1898 as their moving date. Ward’s 1899 directory, which according to its preface was “kept corrected down to the day of going to press, which is usually the last week in November”, lists William Greek Stoneman and the Misses Stoneman’s “Ladies’ School” at the premises. Other information taken from the 1901 census.

- Information taken from an advert on page 3 of the 20 May 1899 Croydon Advertiser. The school may have been named to reference Girton College in Cambridge, which was founded as a women’s college in 1869. However, Girton College Archive tell me that neither Mary nor Lilian is listed in the college’s 1869–1946 register of members (via email, 6 May 2016). On their suggestion, I also tried Newnham College and Homerton College, but similarly the archives staff were unable to find either woman in their registers (via email, 9 May 2016 in both cases).

- The governess may have been attached to the school, or she may have been there for the benefit of William’s 8-year-old grandson, Ronald, who is also listed in this census.

Information on William’s death and legacy taken from the GOV.UK “Find A Will” search. The school is listed on London Road in Ward’s directories up to and including 1910, whereas William vanishes from these listings after 1908. The 1911 census lists Mary and her mother at 44 Kidderminster Road, and Lilian as running a school at 66 Avondale Road, South Croydon.

During the Stonemans’ time on London Road, Ward’s directories list 44 Kidderminster Road as being occupied by William Charles Thompson (1899–1909 editions, inclusive), aside from a brief period of vacancy at the end of this period (1910 edition). The Stonemans may have rented their house to William, or he may have been a relative.

For more information on the history of Clark’s College, see the history page on the Old Clarkonian Association website. This website also has a page with a couple of photos of the Croydon branch. The first of these is the North End Lodge premises, while the second is likely the newer premises constructed in the late 1930s; it could possibly be the junior school constructed between 1913 and 1924, but the 1924 inspection report (see below) makes no mention of upper storeys, and this is clearly a two-storey building.

The Croydon branch of Clark’s College is absent from the January 1909 London phone book, but listed at 1 Addiscombe Road in the July 1909 edition; this latter also lists the main premises at “1, 2, 3, Chancery la W.C.” and branches in Brixton, Cricklewood, Forest Gate, Holloway, New Cross, Putney, Surbiton, and Wood Green.

The July 1910 London phone book lists “Clark’s High School (Girls’ School)” at “Girton ho Lndn rd”; the Addiscombe Road branch is also still in place. (Two other Clark’s girls’ schools also appear in this edition, in Brixton and Tufnell Park respectively; all three were absent from the January 1910 edition.) This remains the case in the January 1911, July 1911, and January 1912 editions, but the January 1913 edition simply lists “Clark’s College” at 67 London Road (which, as noted earlier, was renumbered to 97 in 1927). Ward’s directories are in agreement with this; for 67 London Road they list Clark’s High School for Girls in 1911, Clark’s College for Girls in 1912, and Clark’s College from 1913 onwards, while for 1 Addiscombe Road they list Clark’s College from 1910 to 1912 inclusive, “Clark’s College Annexe” in 1913, and “Unoccupied” in 1914.

The name “Girton House” was used until at least 1937, as it appears in an advert for the college on page 7 of the 2 January 1937 Croydon Advertiser.

- These four houses are shown on the 1913 Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, and are still there today as numbers 60–66.

Quotation taken from the Clark’s College report in Private and Preparatory Schools 1924–1934, a collection of the County Borough of Croydon’s Education Committee inspection reports (reference CBC/3/1/14 at the Museum of Croydon). This is also the source of the age of the children in the junior school. Since the junior school is mentioned in this report, but not shown on the 1913 Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map, it must have been built between 1913 and 1924. The report also mentions the playground, which consisted of “[t]he ground at the back of the house, which has been worn bare, and is somewhat uneven in character”.

A low-resolution aerial view of both school buildings in April 1937 is available on the Britain From Above website, though finding the right part of the image is a little tricky. This image was taken from the south-west, from the Parsons Mead side of the site, and hence shows the backs of the buildings with the playground between. To see it as clearly as possible, you will need to register for an account on the site, which allows you to zoom in. Towards the middle-right of the unzoomed image is Croydon General Hospital, and below it is the spire of West Croydon Methodist Church. Clark’s College is to the left of the church, with North End Lodge/Girton House visible as a tall pale building, the playground with two tall trees below, and the three windows of the junior school classrooms below this.

- Information and quotations taken from Private and Preparatory Schools 1924–1934 as cited above.

- The Educator, Vol. XL, No. 1,195 (Jul 1938), p197 (“News from the Centre and the Branches: Croydon”).

A planning application for “Additional school building” at Clark’s College, London Road, was approved on 27 May 1938 (viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices, ref 38/496). The records of this application include a letter dated 20 November 1937 from the Borough Engineer stating that there was a proposal “to demolish the existing School-building, and to erect a new one in the rear, using and extending the present one-storey Class-room Block; with playgrounds for both sexes [...]. On the completion of this to build (or let on building lease to that end) a row of Shops with Flats or Residences over and gardens behind.” The extension work is marked as having been completed by 7 October 1938.

Further corroboration, and the quotation about the new arrangements, are taken from The Educator, Vol. XL, No. 1,199 (Nov 1938), p324 (“News from the Centre and the Branches: Croydon”), which states that “This month has seen us active in Croydon in moving over from the present premises to our new school. Circumstances have compelled this to be done in sections, but at the time of writing all students are at work in the new building [...] The offices still remain in our old building, but before the next number of The Educator it published we expect to have completed the transfer.” The inside front cover of this issue notes that “our journal has to go to press not later than fourteen days before publication”, and the previous issue states on the front cover that “The next issue will be published on Monday, November 7th”, so these words must have been written by late October.

A planning application for “4 shops with maisonettes over (91–97)” was granted on 27 January 1939 and completed by 31 December 1941 (ref 39/23). According to a newspaper article published a few decades later, Clark’s College sold North End Lodge to the South Suburban Co-operative Society in 1937 (“Sold house to Co-op”, Croydon Advertiser, 38 April 1961, page 20, viewed as a clipping in the Clark’s College folder at the Museum of Croydon). The Co-op definitely had these four shops by 1950, as on 20 January of that year it was granted planning permission for new shopfronts at these addresses (ref 50/33).

It’s perhaps worth noting that all this took place a handful of years before the end of John Squire’s original 99-year lease, which as mentioned earlier began on 25 March 1843. However, it’s likely that Clark’s College had also acquired the freehold at some point, and sold this on to the Co-op too.

- Clark’s College is listed at 97 London Road in phone books up to and including the August 1965 Outer London: North East Surrey edition, but absent thereafter. See next footnote for evidence that it was gone by the start of August 1965. Regarding the type of education offered, an article in the 21 December 1962 Croydon Times states that the college’s “commercial and business training section was flourishing and the students in that section made up a quarter of the college’s total strength” (“11-plus unfair, says head”, Croydon Times, 21 December 1962, viewed as a clipping in the Clark’s College folder at the Museum of Croydon).

- Information on change of use is taken from a planning application granted on 11 May 1964 (ref 64/761). A report forming part of an appeal against a later planning refusal (ref 89/1441/P, refused on 22 September 1989 and eventually granted with conditions on 8 July 1990) includes a letter from British Telecom, Delta Point, 35 Wellesley Road, dated 18 September 1989 and stating that 89D London Road, Croydon, was “occupied by the GPO and its successors, ie Post Office Telecommunications and British Telecommunications plc, from 1 August 1965 until 24 June 1987 for the purposes of the Post Office. This use included offices, storage, telecommunications equipment repair and vehicle parking and the first three uses were in varying proportions during the period of occupation.” The 1970 1:1250 Ordnance Survey map makes it clear that 89D London Road was the old Clark’s College building.

- The March 1985, April 1986, and April 1987 Goad plans show the Co-op site as “(South Suburban Co-operative Society) vacant”; the March 1990 edition shows it as “new Co-oper store und/constn (opening 1992)”; and the June 1991 edition shows it as “Co Op Superstore”, with a “Shoppers Car Park” extending out to the road where the four shops originally were. (I’ll discuss this redevelopment in more detail in a future article.) The “derelict” assessment of the old GPO building is taken from a planning application which describes it as “redundant & derelict office accommodation” (ref 92/0769/P, granted on 4 August 1992).

- The planning application references are 89/1441/P (initially refused by granted with conditions after appeal on 8 July 1990), 90/2079/P (granted to Gatenet Ltd, 805 Salisbury House, 31 Finsbury Circus, on 29 January 1991 for “Erection of three storey building comprising 6 class B1 units [offices, research & development, certain industrial processes]”), and 92/0769/P (granted on 4 August 1992 to Lotus Leisure Group Ltd, Hobbs Court, Jacob Street, SE1 for “erection of 2 three storey office buildings with link walkway”). The earliest documented mention I’ve found of Stonemead House is in the first edition of Shop ’Til You Drop, which was probably published around 1998–1999.

- Planning application references 92/0769/P and 01/1204/P respectively.