West Croydon Methodist Church at 93 London Road has been standing in its present form since the late 1950s. However, part of the current building is rather older, and indeed the church’s time at this site dates back to the turn of the century.

A brief discussion of Methodism

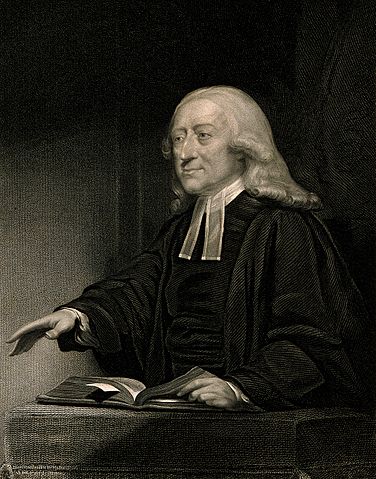

Methodism is an evangelical branch of Protestant Christianity with its origins in the work of John Wesley. Born in Lincolnshire in 1703, John entered the University of Oxford in 1720 and gained his Bachelor’s degree as a member of Christ Church before being elected a Fellow of Lincoln College in 1726 and taking his Master’s degree a year later.

While at Oxford, he and his younger brother Charles were members of a Christian network that attracted several more-or-less mocking nicknames including the Holy Club, the Godly Club, the Sacramentarians, and the Methodists.[1] The latter of these nicknames must have resonated with John, as he retained it even after leaving Oxford and while developing his Christian philosophy.

Although ordained as an Anglican minister, John’s determination to share the Christian message wherever he felt it was needed led him to move away from many of the Church’s traditional practices, and his embrace of open-air “field” preaching and non-ordained “lay” preachers became a significant driver behind the spread of Methodism. Nevertheless, he considered himself as remaining within the Anglican tradition throughout his life, and it was only after his death in 1791 that Methodism came to be a truly separate denomination.[2]

1700s: The beginnings of Methodism in Croydon

Methodists have been present in Croydon since at least the 1780s. In his Methodism in the Purley Circuit, Rowland C Swift quotes a description of the Methodists of Croydon parish in 1788:[3]

There is a small Methodist meeting, Licensed, where about 30 persons meet on Sundays at 11 o’clock, and about 100 at six in the afternoon. No administration of the Sacraments. It is in a declining state. The Teacher is Mr. John Overton, calico printer of Mitcham, 26 years of age, married and of a good character. He is paid 6/- [£40.80 in 2015 prices] a week; he is about to leave his meeting and is to engage another teacher from London. This meeting is supported by contributions and monthly collections which together with £4 [£544] per annum left by a Mrs. Thomas, amount to £40 or £50 [£5440–£6800] per annum. Rent and Taxes £12 [£1632] per year.

1800s: North End and Tamworth Road

As Swift points out, however, the vicar quoted above “was misinformed about the declining state of the Methodist society”, and by 1829 the Methodists had their own Wesleyan Chapel just off North End.[4]

The Methodists also owned the land behind this chapel, running down to Tamworth Road, and a couple of decades later they took advantage of this by building a “handsome and more commodious chapel” with a frontage on Tamworth Road. After this opened in early 1858, the old chapel remained in use as a Sunday school.[5]

1890s–1900s: The move to London Road

By 1891, membership at Tamworth Road was over 300 people,[7] and thoughts must have turned to expansion. Moreover, the site of the chapel was somewhat tucked away from the main streets of the town, down alongside the railway line to Epsom, and so a move somewhere more prominent likely seemed a good idea.[8]

Around this time, the house and grounds of North End Lodge came onto the market. This was a large house, built between 1835 and 1844 with extensive grounds fronting onto the west side of London Road.[9]

A syndicate of Methodists bought both house and grounds at auction on 15 May 1893, at a total cost of £3,800 (£440,000 in 2015 prices).[11] They then rented out the northern part of the grounds, including the house, to a private school, but retained the southern part in order to build their new church.[12]

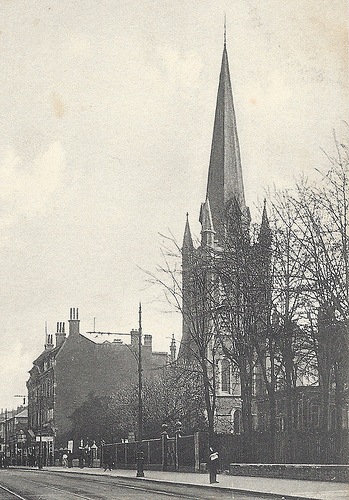

Plans were drawn up by architects Gordon, Lowther & Gunton. The new church would be in “decorated Gothic” style and made of “red brick, freely treated with stone”, with a roof “covered with Broseley tiles”. The interior would “have a gallery on three sides, with a large apse for the organ and choir”, and the main entrance would be “through a spacious narthex and through the tower”. The tower itself would be surmounted by a spire, the two together “rising to a height of about 120 feet” (37 metres). E J Saunders of Croydon was chosen as the builder.[13]

The memorial stones were laid on 20 September 1899, and the church was formally opened just under a year later, on 6 September 1900. The total cost of land and building was £16,800 (£1.86 million in 2015 prices).[14]

The new church could seat 1,000 people — 623 on the ground floor, 344 in the gallery, and 33 in the choir stalls. The Sunday school attached to the church consisted of a hall plus twelve individual classrooms, accommodating around 500 children in total, and space was also found for a “church parlour”.[15]

An article in the January 1905 Croydon & County Pictorial and Surrey Magazine describes the church at this time:[16]

The services there are of a most hearty type, on thorough Methodist lines, evangelical and devotional. On Sunday evenings there is an attendance of between 700 and 800[.]

As well as the Sunday services, the article also mentions a “Young People’s Service” on Wednesday evenings, a “class held for women on Thursday afternoon by Miss A. Brown [...with...] an average attendance of 200”, a “slate club of 150 men and 80 women”, a “temperance sentiment”, a “very good Band of Hope”, and a “Men’s Meeting on Friday evening, which is taken by the Pastor himself”.

Despite the size of the Sunday school, it seems that only five years after opening it was already too small for the number of children wishing to attend; the article goes on to describe the opinion of the then-Minister, Rev George E Cutting, that:

[...] there is an excellent Sunday school, its usefulness only being limited by the want of room to carry on the work. It has increased so much since the church removed from Tamworth Road that the provision for it is now found to be very insufficient.

1920s: Renovation and expansion

It’s unclear whether anything was immediately done about the lack of Sunday school space. However, the 1920s saw the opening of a new “junior school hall”, which must have relieved the congestion somewhat. Designed by architect Hugh Macintosh and formally opened on 14 September 1927, the new hall was part of an extensive renovation scheme which also included “re-wiring of the lighting apparatus in the church, repairs to the organ, cleaning of the interior of the church, re-tiling of the roof and re-laying of the drainage system.”[17]

1950s: Demolition and rebuilding

By the late 1950s, however, it was clear that the church building — only just over half a century old — was no longer fit for purpose. The brickwork was badly eroded, the organ was in disrepair, a new heating system was needed, and the current congregation was simply not large enough to justify the upkeep of such a large building. Rather than raise the £12,000 that was estimated as necessary for repairs (£261,000 in 2015 prices), the church trustees made the decision to demolish the old church and spire, and refurbish the large church hall to create a new church with a modern heating system as well as a new organ. The land thus released would be sold to a commercial concern for building of shops and offices.[18]

The final service in the old church was held on Sunday 16 June 1957, and the first in the new church a week later. Speaking to the Croydon Times a couple of months later, Rev D R Evans described the swift changeover:[19]

Immediately after the last service a band of church workers dismantled the stage in the large hall and cleaned it from top to bottom including scraping the floor. They then brought ten feet pews from the church and within the week the hall was ready for use as a church.

By early 1958, “[o]nly a skeleton remained” of the old church,[20] and in September of that year, planning permission was granted for a new retail/office building on the now-cleared site. By October 1959 this had been constructed and occupied.[21]

As the old church hall had now been transformed into the new church, a new church hall was also needed. This was constructed from scratch, and formally opened on Saturday 4 April 1959:[22]

The large congregation filled the bright and spacious new building and watched with interest as Miss M. Marriage ceremoniously unlocked the door from the inside in answer to the formal knocking of Rev. J. W. Watts, the superintendent minister.

The superintendent minister was followed in by ministers and clergy, and the Mayor and Mayoress of Croydon, Ald. [Alderman] H. Lock Kendell and Mrs. Kendell.

1950s–1970s: The saga of the organ

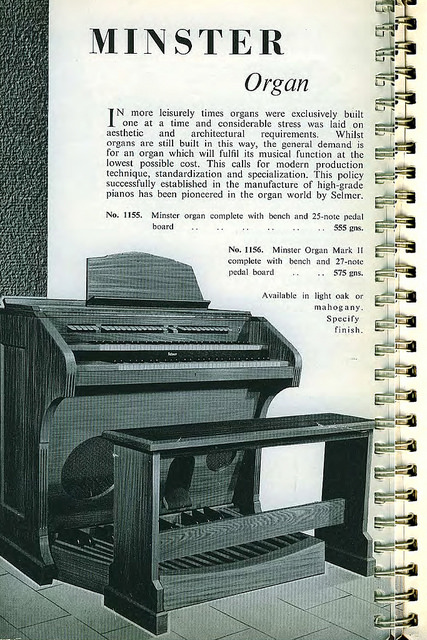

When the old church was demolished, the old church organ was removed and sold as scrap, and the money put towards the purchase of a new organ — “a Selmer ‘Minster’ electronic two-manual” which cost £560 (£11,801 in 2015 prices). This was dedicated at a special service on Saturday 22 February 1958, with Norman Hunwick of Shirley Methodist Church as guest organist.[23]

This, unfortunately, proved not to be the wisest of purchases, as the new organ seems to have rapidly deteriorated. Just over a decade later, the Croydon Advertiser characterised its sound as “a queer noise”, and reported that it “would give up the ghost halfway through the service and a piano would have to take over.” Eventually, “even the organist gave up and refused to play the instrument.”[24]

A new pipe organ was bought from Geo Osmond & Co of Taunton at a cost of around £2,500 (£31,875 in 2015 prices), and debuted at a recital by organist Alex Godin on Saturday 19 June 1971.[25] A report in the following Friday’s Croydon Advertiser gives some idea of the occasion:[26]

There was only standing space on Saturday for the dedication and opening recital which followed. [...] Alex Godin is well known as a theatre organist and had given several recitals in the church hall on his own instrument to raise funds for the new organ. [...]

First came the second and third Liturgical Preludes by George Oldroyd, at one time organist of St. Michael’s Church, Croydon. [...] A Berceuse by Armas Jarnefelt enabled the flute stop to be heard as a gentle accompaniment to the beautifully shaped melody [...] A smooth performance of Quilter’s “Non Nobis Domine” showed the organ in yet a lighter mood, with an ample use of the open diapson on the great organ. [...] The recital ended with Stephen Adams’ “Holy City,” which demonstrated the range of power of the organ.

1970s–1990s: Sheila Szzvanowski’s memories

Sheila Szzvanowski, who along with her husband Carl attended the church from around 1974 to around 1994, kindly shared her memories of this time:[27]

We were Methodist but we got married in ’66 and we’d been trying to find a church that we really liked when we moved to Croydon [...] and then we [...] renewed our membership there. Transferred our membership from Streatham.

We used to go to the community night meeting on a Wednesday. They’d have people like Ron Cox [a local historian], lots of talks, music evenings, [and] about once every two months there was this, like, worship meeting [...] for people from the community, not just church people. [...The music evenings were] usually people with recordings [...but] there were two or three groups of live musicians that did come occasionally.

[...The services themselves] were very much the sort of services that everyone used to have, with about four hymns, a couple of lots of prayers, sermon [...] — very standard.

While we were there, we were getting a lot more people from overseas [...] it was about 30% West Indian, 30% West African, 20% Asian, and just 20% ethnic white. [...] About ’86 [...] I was the church secretary, but the treasurer, the organist, and one of the other senior members of the church council all moved away within a month or two [...] they decided, the church stewards [...], they should get people, one from each ethnic group [...] and most of the people coming from overseas had taken full part in their own services in their home countries, and they didn't like to push themselves, but they were so pleased to be asked.

2000s: West Croydon Methodist Church today

When I visited the church just before the start of a Sunday service in March 2016, I was warmly welcomed and introduced to Rev Francis Nabieu, Senior Steward Rose Cummings, and church historian Josef Hopeson-Sowah. Rev Nabieu kindly allowed me to stay for the service, which was themed around Mothering Sunday.

The service included congregational hymns (with words projected on a screen to ensure everyone could see them), harmonies from the choir, and accompaniment on organ and drumkit. Readings were from Exodus 2:1–10 and John 19:25–27, and Rev Nabieu’s sermon focused on the different meanings of motherhood. Every woman in the congregation was given a bunch of daffodils, and the church’s Mother of the Year award was presented for the first time. After the service, a buffet lunch of chicken, spring rolls, samosas, fried plantains, chips, coleslaw, sandwiches, and cakes and pastries was served by the men of the congregation.

One thing that impressed me about my visit to the church was that although the day was focused on celebrating motherhood, Rev Nabieu took care to point out that this can be a painful subject in many cases, and to encourage the congregation to also value women who are not mothers themselves. I also noted the broadness of scale of matters brought up during the service — from the birth of a congregationer’s third grandchild, to the 59th anniversary of Ghana’s independence (which this year coincided with Mothering Sunday).

Thanks to: Rev Francis Nabieu, Josef Hopeson-Sowah, Rose Cummings, Carol, Pamela, and everyone else who welcomed me to West Croydon Methodist Church and encouraged me in my project; Sheila Szzvanowski; Steve Russell of the Vintage Hofner site; Meg Hewitt (meghewitt@gmail.com), for a swift and professional transcription of my interview with Sheila; Brian Lancaster, for research advice; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers Henry and Kat. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

- Henry Braun points out that “Sacramentarians were a Reformation-era sect, so its use is definitely satirical, while Methodist is new” (online conversation, 16 April 2016).

- For more information on the history of Methodism, see the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entries on John Wesley and on the Holy Club. (This requires a login, but a Croydon Libraries library card number will suffice.)

Rowland C Swift, Methodism in the Purley Circuit (1980, viewed at the Museum of Croydon under shelfmark S71 [287] SWI). This quotation appears on page 7 and is described as coming from “the return for the parish of Croydon to Archbishop Moore’s visitation in 1788”. A visitation essentially consisted of a visit by a bishop or archbishop to the district over which he had authority, including various aspects such as legal formalities, social activities, and answers provided by the parish clergy to various questions about the religious activities within their parishes. Further information on visitations can be found in the Introduction of Archbishop Thomson's Visitation Returns for the Diocese of York, 1865 by Edward Royle and Ruth M Larsen (Borthwick Publications, 2006, viewed online at Google Books), as well as in the Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide: Visitation Articles and Returns (PDF; which, incidentally, also lists Archbishop Moore’s 1788 Returns as being available for viewing at the library).

Swift also gives a quotation from the 1758 Returns, in which the vicar of Croydon states that “I don’t know that there are any Methodists or Moravians in the parish.” (Methodism in the Purley Circuit, page 7).

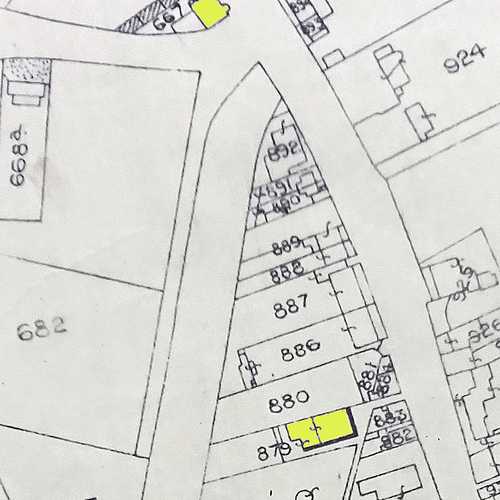

- Swift’s statement about misinformation is on page 7 of Methodism in the Purley Circuit, where he also notes that “in any case an evening congregation of one hundred and collections of up to £50 a year [...] cannot be regarded as evidence of a declining cause”. Date of North End chapel is taken from Jeremy N Morris, “The Origins and Growth of Primitive Methodism in East Surrey”, Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society 1992, 48(5): 133–149 (PDF) which cites “Croydon Wesleyan Chapel, North End: registers of burials and baptisms 1829-1848” as a source in footnote 16, implying that the chapel was there by 1829. The site of this chapel is shown on the 1844 map in the main article.

- Ownership of land is taken from the 1844 Tithe Award, which states that the whole of plot 879 (see map in main article), consisting of “Chapel, house, yard and garden” belonged to “Trustees Wesleyan Chapel”. Quotation about the new chapel is taken from page 9 of Methodism in the Purley Circuit, though it isn’t made clear who Swift is quoting. Information about the new chapel as well as the situation and continued use of the old chapel is also from this source. Ward’s 1900 directory confirms that the new “capacious building was opened early in 1858, the building previously used as a chapel being devoted to the Sunday School” (entry under “Tamworth Road Wesleyan Methodist Church” on page xxix).

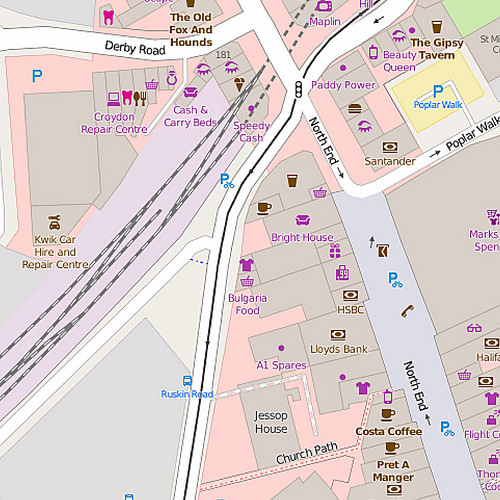

- In the two newer maps, the railway lines run southwest from top-centre to bottom-left and Tamworth Road lies between the railway lines and North End. In all three maps, Derby Road runs west off North End at the very top and Poplar Road runs northeast off North End a little further down. Extracts from 1844 Tithe Award map and 1896 Town Plans reproduced courtesy of the Museum of Croydon. Extract from 2016 OpenStreetMap © OpenStreetMap contributors, data available under the Open Database License, cartography licensed as Creative Commons cc-by-sa.

- Methodism in the Purley Circuit gives Society of Methodists membership figures on page 11: 308 at Tamworth Road in 1891, though only 268 in 1896. The fall in membership may have been due to transfer to other Methodist churches, as numbers increased at most of the other Societies listed, and in particular there is a Thornton Heath Society with 40 members in 1896 that was not in existence in 1891.

- A Croydon Advertiser article on the laying of memorial stones at the base of the new London Road chapel describes a speech by Rev Walford Green, stating that “he thought [the audience] would all agree with him that the Methodists [...] were doing right in seeking to come to the front [...] and not being content to take up their abode in back streets and out-of-the-way places”, and another by Mr S Rogers stating that he “had advocated the present step [of building a new chapel] for the last seven or eight years, and he thought a wise step had been taken” (“A new Wesleyan chapel for Croydon”, 23 September 1899, p2).

- I’ll discuss North End Lodge further in my article on 95 London Road.

Image reproduced courtesy of the Museum of Croydon. The discontinuity on this map is due to these parts of the land appearing on different map sheets, and so I’ve had to join them back together. I’ve also rotated this to show the area of interest more clearly — the line of discontinuity runs south on the left side of the image to north on the right side.

The phrase “up to Parsons Mead” is used in relation to the orientation of the map as shown here. In reality, the land actually slopes down significantly from London Road to Parsons Mead.

- “The Sale of North End Lodge”, Croydon Advertiser, 20 May 1893, page 8.

- It’s unclear when and how the syndicate transferred the southern part of the land to the church trustees, but an article in the 8 September 1900 Croydon Advertiser (“Wesleyan Methodism in Croydon”, page 8) states that the cost of the site was £2,400 and that the “law expenses in connection with the transfer” were “defrayed by the syndicate”. The prices here are a little confusing, as the article also notes that the syndicate had no intention of profiting from their purchase: “The seven gentlemen forming the syndicate agreed that the profit made [by renting out the house and northern part of the grounds] should be handed to the trust, and if there was any loss they would pay that themselves”. It’s not at all clear why half of a £3,800 plot of land (and, moreover, the half without the house on it) would be valued at £2,400. Even if one assumes that the syndicate didn’t transfer the land to the trustees until 1900, inflation at the time would only have increased the value of the land to around £3972 (calculation made with 1893 as base year; see acknowledgements for details).

- Details of architecture, and names of architects and builder, are taken from a contemporary Croydon Advertiser article (“A new Wesleyan chapel for Croydon”, 23 September 1899, p2; note however that an article on page 22 of the 24 January 1958 Croydon Advertiser puts the height of the spire at 136 feet, or 41 metres. The 1899 article also states that both architects and builder were Methodists themselves. According to Croydon Council’s Supplementary Planning Guidance for St Helen’s Road Local Area of Special Character (PDF, page 12), E J Saunders also built the bank at 1434 London Road.

Dates of stone-laying and opening are taken from Methodism in the Purley Circuit, and confirmed by articles in contemporary editions of the Croydon Advertiser (“A new Wesleyan chapel for Croydon”, 23 September 1899, p2, and “Wesleyan Methodism in Croydon”, 8 September 1900, p8, respectively). The 1899 article also says that the people who laid the memorial stones were Alderman F P Alliston (Sheriff of the City of London), Councillor G J Allen (Mayor of Croydon), Mr J H Lile, Mrs S Rogers, Mrs W Lisle Williams, Mrs A C Holman, Miss Florence A Holt, and Mr Josiah Gunton. Total cost of land and building is taken from an article in the January 1905 Croydon & County Pictorial and Surrey Magazine (pages 83–84). Price conversion made with 1900 as the base year; using 1893 instead (the year of the land purchase) would give a modern equivalent of £1.95 million.

The 1900 Croydon Advertiser article includes a description of how the new church was funded. Part of the cost was met by a grant of £2,000 from the Metropolitan Chapel Building Committee, and much of the rest by donations. There was still outstanding debt at the point the article was written, though the Tamworth Road church was still to be sold, which would help pay off some of it.

It’s worth noting that the original plans were to omit the spire and add it at a later date, when more money had been raised; the 1899 Croydon Advertiser article states that “the builder’s contract for erecting the church, without the spire — which would not be added at present — was £9,435”, and the 1900 article clarifies that this contract “only included the foundation of the tower to the roof”. However, the latter article also states that the spire was complete by the time of the official opening (and was “covered in oak shingles”).

- Details of Sunday school and numbers of people accommodated in the church are taken from a drawing dated 27 March 1899, included in an April 1900 planning application for “Alterations to W.C.s & Lavatory” at “London Road Wes. Church” (viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices, ref 11234). My notes from viewing this application say I counted eight classrooms in the Sunday school, but the article in Ward’s 1901 Directory states that there were actually twelve; this article is also the source for the figure of 500 children.

- Croydon & County Pictorial and Surrey Magazine, January 1905, pages 83–84 (shelfmark fS70 (OS) at Croydon Museum).

- “Sunday school work”, Croydon Advertiser, 17 September 1927, page 5.

“Methodist church to be demolished”, Croydon Advertiser, 1 March 1957, page 7. Price conversion (see acknowledgements for details) made with 1957 as reference year.

It’s perhaps worth noting that a Croydon Times article from 1958 (“West Croydon church rises again”, 30 May 1958, page 11) blames “war-time bomb damage” for making the building “unsafe”, but I haven’t found any corroboration of this, and in any case a later Croydon Advertiser article (“Methodist church will soon be rebuilt”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 June 1958, page 7) states that problems with the building’s fabric had been known since the 1930s, but “the war prevented anything being done”.

- Dates of last service in old church and first in new, as well as quotation, taken from “Methodists wonder — ‘Where will we go?’”, Croydon Times, 30 August 1957, page 3. This article also states that the “extra pews that could not be used in the hall” were “stored in rooms at the back”; according to West Croydon Methodist Church Centenary 1900–2000 (page 12) they were later sent “to Addington Methodist who were building their own church”.

- “Clearing church site”, Croydon Advertiser, 24 January 1958, page 22.

- See my article on 89 London Road for more information on the new retail/office building.

- “First stage opened in Methodists’ £15,700 scheme”, Croydon Times, 10 April 1959, page 6. According to a Croydon Times article of the same date, Miss M Marriage “[had] been connected with the church for many years” (“New Methodist church hall is opened”, Croydon Times, 10 April 1959, page 7).

- Information on sale of old organ as scrap taken from “New organ at church”, Croydon Advertiser, 21 February 1958, page 10. Specifications, price, and information on dedication of new organ taken from “Church’s new organ cost £5,600 [sic]”, Croydon Advertiser, 28 February 1958, page 7, and a correction to this article, “New organ cost £560 [sic]”, Croydon Advertiser, 7 March 1958, page 7. Price conversion (see acknowledgements for details) made with 1958 as reference year. The 1959 Selmer Trade Catalogue (see image in main article) gives the price of the “Minster” organ as 555 or 575 gns (guineas, where a guinea is £1.1s.0d), which comes to £582.15s.0d or £603.15s.0d rather than £560, but this discrepancy is likely due to a price rise between the purchase of the organ and the production of the 1959 catalogue, as it’s of the same order as the rate of inflation around that time.

- “The organ that kept giving up the ghost is dead!”, Croydon Advertiser, 25 June 1971, possibly on the front page but my note of the page number is missing.

- “The organ that kept giving up the ghost is dead!”, Croydon Advertiser, 25 June 1971. This article gives the cost as £2,400, whereas West Croydon Methodist Church Centenary 1900–2000 (page 13) gives a figure of £2,564, so I have hedged my bets and used a figure in between. West Croydon Methodist Church Centenary 1900–2000 (page 13) is also the source for the name of the maker of the organ; and its author, Josef Hopeson-Sowah, confirmed to me that this is the same organ that’s in the church today (via email, 10 April 2016).

- “Recital on new organ”, Croydon Advertiser, 25 June 1971, page 27.

- Audio-recorded and transcribed interview with the author, 4 March 2016.