Shadi Bakery at 79 London Road opened in mid-2012, with two tandoors baking fresh naan and chapati to order throughout the day.

1830s–1840s: Construction of the original building

The current building, which forms part of a terrace with numbers 81–87, was not the first to be constructed on this piece of land. The plot was originally part of the area of common land known as Parsons Mead, which passed into the hands of the Caldcleugh family following the Parsons Mead Inclosure Act of 1823. After the death of Elizabeth Caldcleugh in February 1835, Parsons Mead was split up and sold in lots at auction on 23 May 1835.[1]

The parcel of land on which numbers 79–87 now stand was bought in that auction by Henry Bance. By 1844, Henry had used the land to build a pair of semi-detached houses, which he rented out to Henry Read (left-hand side, i.e. roughly the site of numbers 79–83) and J Lewland (right-hand side, i.e. roughly the site of numbers 83–87). These were among the first houses to be built on the ex-Caldcleugh plots; as of 1844, there were no other buildings between here and the Croydon Station Inn (later renamed to the Fox & Hounds) at the southern end of London Road.[2]

Early 1850s: Frederic Selmes

By 1851, Henry Read had been replaced by Frederic Selmes, a 40-year-old hop factor — a sort of middleman between the farmers who grew the hops, and the merchants who sold these hops to brewers.[3] Frederic may have chosen to live here in order to be close to the railway station, as his place of business was in Southwark — specifically, on Borough High Street, near London Bridge Station.[4]

Southwark and Bermondsey at this time formed the centre of hop trading in London, and Frederic would have been surrounded by other hop factors as well as hop merchants. Until 1869 he worked in a partnership known as Selmes & Masters, along with one William Masters, and later entered another partnership, Selmes & Jackson.[5] He continued as a hop factor until his death on 15 November 1887, at Morley’s Hotel in Trafalgar Square.[6]

1850s–1890s: John Baines, Sarah Finch, and Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith

Frederic’s association with London Road, though, ended as early as 1855, when he was replaced by John Baines — and John Baines himself was gone again by 1858.[7] However, this rapid turnover settled down with the arrival of Sarah Finch, in place by late 1858 and remaining for around two decades.[8] Sarah was a widow who lived with her unmarried daughter Louisa and derived her income from private investments. She was in her late 60s when she arrived on London Road, and remained here until her death nearly two decades later, on 7 August 1876.[9]

Next to arrive was Dr Walter Hugh Montgomery Smith, who had his surgery a few doors down at number 61. Walter moved here from number 57 around 1877 and remained until around 1896, when he took up residence at his surgery. (See my article on number 61 for more information on Walter.)

Late 1890s: Demolition and rebuilding

Walter’s move to his surgery may have been a forced one, as his house and the other half of the semi-detached pair were both scheduled for demolition. By late 1897, the two older houses were gone and the construction of a new 5-property terrace had begun. Construction was complete by the end of 1898.[10]

1900s–1910s: Butchers and dressmakers

The life of the new number 79 began rather uncertainly. A butcher known as C Vince was in place by 1900, but replaced by a different butcher, H A Newbury, by 1901. H A Newbury in turn was gone again by 1902.[11]

The next occupant was to last rather longer. Mary Dowden and her daughters Florence and Margaret moved here from 16 Derby Road, just around the corner, some time between April and November 1901. A widow in her mid-50s, Mary worked as a draper and dressmaker, assisted by Florence and Margaret. The family remained here until around 1913.[12]

1910s–1930s: Sundriesmen, tailors, and hairdressers

The building remained vacant for the next four or five years, before the arrival of D W Greer & Co, wholesale sundriesmen. It’s not clear what type of sundries this business sold, but in any case it was only here briefly; in place by 1918 but gone again by 1920.[13]

The next couple of occupants saw a return to the clothing business. O Barnett, ladies and gents tailor, arrived by 1920 but was replaced around 1922 by another tailor, S Ring, who in turn was gone by 1925.[14]

Next to arrive was a hairdressers known as A J Millen & Sons, possibly also trading as Richard Ede. This arrived around 1925 and was gone again by 1930.[15]

Around 1930, the tailors and outfitters next door at number 81 — Lewis & Lewis — expanded its business to number 79. It remained here until at least around 1940.[16]

1940s–1960s: Barnet Cooklin, builders merchant

It’s unclear what the premises were used for during the bulk of the 1940s,[17] but by 1949 they were occupied by Barnet Cooklin, a builders merchant specialising in fireplaces and sanitary ware (i.e. toilets and washbasins). This remained until the mid-1960s, albeit with a rename to Cooklins (Croydon) Ltd somewhere along the way.[18] By 1964 its shopfront advertised a stock of 80 different fireplaces priced from £8/10s/0d (£153.85 in 2014 prices), “Complete with fire back, fret & basket”.[19]

Late 1960s: The Hungry i

By late 1966, Cooklins had been replaced by a business unlike any that had come to number 79 before: the “Hungry i” coffee bar. This unusual name may have been inspired by the famous nightclub of the same name in San Francisco. The Croydon version stayed open late into the evening, and offered “non-stop pop music, played by a popular disc jockey” three nights a week.[21]

The basement was home to a folk and blues night every Tuesday, launched on 18 June 1968 by Croydon residents Jerry Leech and Anne Statter, with folk singer Shirley Collins as guest artist on the opening night, supported by Dick Hook of the Redhill Folk Club. Half a century later, Jerry still had fond memories of this:[22]

Anne (we are still together!) and I started the club in 1968 in part as a Croydon equivalent to the now legendary Les Cousins in Soho. While it lasted it bought some of the greatest names in folk and blues at that time to Croydon. [...] On many Tuesday evenings there were queues up the stairs from the cellar and along the street for the chance to see and listen close up to American performers like Spider John Koerner or Stefan Grossman or British singers such as Al Stewart, Sandy Denny, Shirley Collins or the Young Tradition all of whom went on to shape our music.

[...] We advertised the club every week through the Melody Maker and the Croydon Advertiser. They usually carried a profile and often an interview with the performers. I do remember travelling on buses at night each week beforehand around Croydon and South London with buckets of wallpaper paste and rolls of posters “spreading the word” — a 1960s version of Banksy! The club’s first night was marked with coffee pouring through the floor from the restaurant above. Another night we managed to turn off the lights as we left — and the restaurant freezer in the cellar!

Dave Harwood, who was born in Mayday Hospital in 1948 and lived on Kimberley Road until 1970, also recalled the folk and blues night:[23]

I paid 1 shilling and sixpence to become a member of the Hungry i club and saw a variety of different folk & blues artists (as well as the odd poet!) for which I was charged five shillings entrance fee each Tuesday evening. [...] my membership card [...] was a handmade affair on red card and had a large lower case i on the front [...]

1970s–1990s: Town Talk, Naz Curry Centre, The India Cottage, and Jaipur Tandoori

By 1971, the next era of 79 London Road had begun — that of Indian and Bangladeshi restaurants. The first of these was called Town Talk (or possibly Town-Talk). It was fully licensed, open until 1am every day, and advertised specialities including stuffed parathas, samosas, prawn pakoras, and shami kebabs. Those unfamiliar with Indian food were reassured that “the attendants will respectfully advise and explain combinations and techniques of Indian dishes”.[24]

Town Talk was replaced by the Naz Curry Centre around 1972–1973, which lasted until around 1976 before being replaced in turn by The India Cottage (c.1977–c.1988) and then Jaipur Tandoori (June 1990–c.1992).[25] Jaipur Tandoori in particular was the subject of several advertising features in the Croydon Advertiser, many of which included a description of the interior:[26]

The decor is fresh and pretty, with mirrored walls adding to a feeling of spaciousness, and wooden screens which divide the dining area into private booths. The pretty blue decor is accented with white — elegant and relaxing. A welcome comfort is the air-conditioning which keeps the temperatures cool when the curries are hot! [...] The Jaipur has 44 covers in the main restaurant [...and...] a second “function room” downstairs with its own bar, where 25 can dine in comfort and privacy.

Despite all the different names, many or perhaps even all of these restaurants seem to have been run by the same person: Saad Ghazi.[27] Born in Sylhet (now part of Bangladesh) in the mid-1940s, he moved to the UK while still in his late teens. Two decades later, he co-founded the Bangladesh Welfare Association, which for a time held its meetings at his London Road restaurant.[28] He also had another restaurant in Isleworth, the Khyber Pass.[29]

1990s–2000s: London Tandoori, Al-Amin, Akash Tandoori, and Victoria Spice

Jaipur Tandoori appears to have been the last incarnation with Saad Ghazi in charge. London Tandoori, which opened in February 1992, made a point of advertising itself as “Under new management”. It offered “Reasonable prices, home style cooking, friendly service”, and a “take away service”.[30]

By 1995, however, London Tandoori had been replaced by Al-Amin, and this in turn was replaced by Akash Tandoori by 1997 and then Victoria Spice by 2001.[31] Little evidence remains about what types of restaurant these were, though judging by the names they were all likely Bangladeshi or Indian.[32] The last of them, Victoria Spice, closed in March 2004.[33]

Mid-to-late 2000s: Mantiana, Ephesus, and Yasmin

The premises remained vacant for a year or so after this, but by May 2006 were occupied by Mantiana, a Mediterranean cafe, bakery, and patisserie. By July 2007, however, this had been replaced by a “fast food restaurant” called Ephesus, and by July 2008 this too had been replaced by Yasmin, a Lebanese and Middle Eastern cafe/restaurant which also offered shisha.[34]

Early 2010s: Shameran

Yasmin was followed by Shameran, a Kurdish restaurant serving chicken and lamb kebabs, grilled fish, soups, and stews until 3am every night.[35] Justin Fores described it on the Chowhound food forums:[36]

[The] food is solid homestyle Kurdish fair [fare] at extremely low prices. [...] [£]6.50 can get you a glass of excellent homemade ayran [fermented yoghurt drink] with tarragon, roast lamb, rice, bread, zucchini stew, etc. The staff are extremely friendly and I basically chatted away with them about Iraqi Kurdistan for two hours the second time I ate there. Their Kurdish kebabs are also good and very reasonably priced. Both above meals came with soup too! They've got a sheesha garden in the back too.

Shameran was open by August 2010, but closed again some time between March 2012 and June 2012.[37]

2012–present:

Shadi Bakery opened around June 2012, originally under the name of Shadi Market. Two tandoors were installed as part of this, for baking fresh naan and chapati. Initially it also sold nuts, seeds, dried fruit, pickled vegetables, and sweet pastries such as baklava, but by March 2013 it had scaled back to bread and soft drinks alone.[38] As of October 2015, it sells chapati, naan, and flatbreads stuffed with minced meat, with a couple of small tables for anyone wanting to sit in.

Thanks to: Andy Worden of the Croydon Advertiser; Dave Harwood; Jerry Leech; Justin Fores; Ray Bailey; Stephen Humphrey; the Brewery History Society; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; all at the Croydon Local Studies Library; and my beta-readers Alice and bob. Census data, FreeBMD indexes, and London phone books consulted via Ancestry.co.uk.

Footnotes and references

- For more on the Parson’s Mead Inclosure Act, see my article on 145 London Road. I’ll discuss the Caldcleughs at greater length in my article on Broad Green House.

- Handwritten notations on a copy of the particulars for the 1835 sale (viewed at Croydon Local Studies Library, ref BA268) specify H Bance as the purchaser of this lot. He paid £325 (£36,882 in 2014 prices, according to the Bank of England inflation calculator) for a plot of 80ft 6in by roughly 222ft (around 17,871 square feet, or 1,660 square metres). The 1844 Tithe Award lists the left-hand house as owned by Henry Bance and occupied by Henry Read, and the right-hand house as owned by Henry Bance and occupied by J Lewland. The Tithe Award also shows only building ground and a meadow between these houses and the Croydon Station Inn.

- Gray’s 1851 and 1853 directories list Frederick [sic] Selmes, gentleman, at the premises. The 1851 census lists Frederic [sic] Selmes, age 40, born in Beckley (Sussex), hop factor, plus two servants. Note the discrepancy here in the spelling of Frederic’s given name. He is “Fredk” in the 1861 census, “Frederick” in the 1871 census, and “Frederic” in the 1881 census. The notice of proving of his will (see the GOV.UK “Find a Will” search) uses the spelling “Frederic”, as do all the references to him I’ve found in the London Gazette, as well as his entry in the FreeBMD Death Index, 1837–1915, so this is the spelling I have also chosen.

- The 1882 Post Office London Directory (Small Edition) lists Selmes & Masters, hop factors, at Nag’s Head Buildings, 102 Borough High Street (page 976; Directory downloaded from the University of Leicester Special Collections Online). Southwark historian Stephen Humphrey confirms that the Selmes of Selmes & Masters was Frederic Selmes of Croydon: “On December 31st, 1851, Frederick Selmes, described as a hop factor of Nag’s Head Yard, Borough High Street, Southwark, together with William Masters of the same occupation and address, entered a 21-year lease of a house, showrooms and hop warehouses on the south side of Nag’s Head Yard for the rent of £400 a year. [...] At Croydon, hop factors would not have been close to the growers or to the hop merchants with whom they needed to do business. Frederick Selmes was clearly residing at Croydon but worked in Southwark, which was the normal place of business of the hop trade for many centuries.” (via email, 14 August 2015). Stephen tells me further that his source for the information on the Selmes & Masters lease is a calendar of title deeds which definitely uses the spelling “Frederick”, but that he can’t check the original deed because it’s currently inaccessible “and will possibly remain so until the Old Town Hall in Walworth Road is restored to use, which is unlikely to be before 2019” (via email, 15 August 2015).

- The dissolution of Selmes & Masters is reported on page 4027 of the 16 July 1869 London Gazette. Information on Selmes & Jackson provided by Stephen Humphrey: “By 1882, the partnership had become Selmes and Jackson, and occupied premises at Calvert’s Buildings (15 Southwark Street) and at 52 Borough High Street.” (via email, 14 August 2015). For more information on hop factors and the Borough, see Chapter 5 of Celia Cordle’s Out of the Hay and into the Hops, University of Hertfordshire Press, 2011 (viewed online at Google Books) and/or Stephen Humphrey’s The Hop Trade in Southwark, in issue 123 of Brewery History.

- Date and place of Frederic’s death, and his profession at the time, are taken from the GOV.UK “Find a Will” search.

- John Baines is listed in Gray & Warren’s 1855 directory, while the October 1858 Poor Rate Book instead lists Sarah Finch. After leaving these premises, John may have moved just up the road to a newly-constructed semi-detached house just south of Montague Road. Poor Rate Books and street directories list a Baines/John Baines at contemporary number 42 from around 1858 to around 1869, an address which Gray & Warren’s 1855 directory lists as one of two “Semi-detached residences, erecting”. (That address has no modern equivalent; it was renumbered to 83 around 1890 and again to 113 around 1927, but was demolished some time after 1939 and is now occupied by offices.) This could however have been a different John Baines!

- Sarah Finch is listed in Poor Rate Books from October 1858 onwards (sometimes as “Sarah” and sometimes as “Sar”), and in street directories: Gray & Warren’s 1859 and 1861–62; Simpson’s 1864; Warren’s 1865–66 and 1869; Wilkins’ 1872–3; Ward’s 1874 and 1876; and Wilkins’ 1876–7. Ward’s 1878 instead lists W H M Smith, M.D.

- The 1861 census lists Sarah Finch, widow, age 70; her daughter, Louisa Finch, unmarried, age 30; and their servant, Kate Gregory, unmarried, age 28. The 1871 census again lists Sarah and Louisa, with a different servant; Hannah [something beginning with “E”], unmarried, age 26. It is of course possible that Louisa was merely visiting on one or both occasions, but if on both, this does seem like it would be quite a coincidence. The 1861 census describes Sarah as a “Fund Holder” — that is, someone who had a private income from investments. See footnote 4 of my article on 37 London Road for more information on this term. Her date of death is taken from the GOV.UK “Find a Will” search, which also states that she died at home on London Road and left “Effects under £12,000”.

- Ward’s directories list the “Unoccupied” older semi-detached houses in 1897, “five shops building” in 1898, and “four shops unoccupied” plus one occupied (Frederick Randall, ironmonger, in the modern number 87) in 1899. The prefaces of the 1898 and 1899 editions state that the data “is kept corrected down to the day of going to press, which is usually the last week in November [the previous year]”. The property records held at Croydon Council’s planning department include the original record, a small card which states “London Road / 5 Houses & shops / Bannerman / April 1897 / Nearly opposite General Hospital”. Bannerman may have been the builder. Comparing with Ward’s directories, perhaps April 1897 was the date that construction began.

- Ward’s directories list C Vince in 1900, H A Newbury in 1901, and Mrs Dowden from 1902. The 1901 census simply lists a “Shop”.

- The 1901 census, conducted on the night of March 31/April 1, puts Mary, Florence, and Margaret at 16 Derby Road. Ward’s 1902 directory puts “Mrs Dowden” at 55 London Road (modern 79); the London Road pages in this directory are dated 25/11/01. The 1911 census lists Mary, Florence, and Margaret all at 55 London Road and all working “at home”, with Mary as “Employer” and her daughters as “Worker”s. Mrs Dowden, Draper and Dressmaker, appears in Ward’s directories from 1902 to 1913 inclusive.

- Ward’s directories list the property as unoccupied from 1914 to 1917 inclusive, and as occupied by D W Greer & Co in 1918 and 1919. Several types of sundriesmen exist or have existed, such as market sundriesmen selling paper bags, signs, and tags (see the Spitalfields Life article on Gardners’ Market Sundriesmen for a modern-day example); butchers’ sundriesmen selling sausage casings (modern example) and wrapping paper; and brewers’ sundriesmen selling shives, spiles, faucet plugs, corks, and bottling taps (see my photo of a display of such items in a pub in Brentwood, included above).

- Ward’s directories list O Barnett in 1920, 1921, and 1922; S Ring in 1923 and 1924; and A J Millen & Sons in 1925.

- Ward’s directories list A J Millen & Sons, Hairdressers, in 1925, 1926, and 1927; Richard Ede, Hairdresser, in 1928; A J Millen & Sons, Hairdressers, in 1929; and Lewis & Lewis, Tailors & Outfitters, in 1930.

- I’ll discuss Lewis & Lewis further in my article on 81 London Road.

- A photograph (ref PH/96 2702) in the collection at the Croydon Local Studies and Archives Service, annotated “Late 1940s”, seems to show the property as vacant.

- B Cooklin, “Bldrs’ Mcht”, is listed at 79 London Road in phone books from the 1949 London edition to the 1959 Croydon edition inclusive; Cooklins (Croydon) Ltd, “Bldrs Mchts” is listed from the March 1960 Croydon edition to the June 1965 Croydon edition, inclusive. Kent’s 1955 and 1956 directories list Barnet Cooklin, “Fireplaces & Sanitary Ware”.

- Details of shopfront taken from a drawing dated March 1964, included in a later-abandoned planning application for a Chas Butler betting office at the premises (ref 64-511, viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices). Price conversion via the Bank of England inflation calculator.

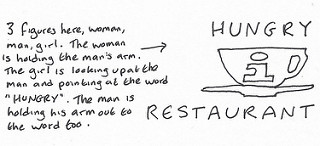

- Ref A4390, viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices. I have not attempted to replicate the font of “HUNGRY” or “RESTAURANT”, and have described the top-left part of the sign instead of sketching it.

- See Wikipedia for more information on the San Francisco version. Information about the Croydon version is taken from Rockin’ and Around Croydon by Chris Groom, p131. The quotation about “non-stop pop music” is quoted in the book, but the source isn’t given.

- Information about opening night taken from Rockin’ and Around Croydon, p131. Other information provided by Jerry Leech, via a comment on this article (6 September 2023) and via email (20 September 2024). I have edited Jerry’s words very slightly to add some formatting and an apostrophe.

- Via email, 3 July 2015 and 4 July 2015.

- Town Talk, Indian Restaurant, is listed in the August 1971 and February 1972 Croydon phone books. All other details are taken from an advertisement on page 2 of the 1971 Croydon Official Guide, which is headed “Town-Talk [sic] Restaurant (Indian)”.

- Naz Curry Centre is listed in Croydon phone books from March 1973 to January 1976 inclusive, and the August 1974 Goad plan. India Cottage Restaurant is listed in Croydon phone books from July 1977 to 1988 inclusive, Brian Gittings’ 1980 survey of central Croydon shopfronts, and Goad plans from March 1984 to April 1987 inclusive. Jaipur Tandoori Restaurant is mentioned in an article in the 26 October 1990 Croydon Advertiser as having opened “four months ago”, so around June 1990; it’s also listed in the June 1991 Goad plan and the February 1992 Croydon phone book.

- Quotation about Jaipur Tandoori interior is taken from an article on p18 of the 26 October 1990 Croydon Advertiser, viewed on microfilm at Croydon Local Studies.

The 2014 British Bangladeshi Who’s Who (available as a PDF online) states that Saad Ghazi opened the Naz Curry Centre in Croydon in 1969 (note however that I’ve not been able to find the Naz Curry Centre in Croydon phone books before 1973). His LinkedIn profile states that he also owned the India Cottage, and this is corroborated by an article on page 36 of the 26 February 2010 Croydon Advertiser, which states that “in 1984 the BWAC [Bangladesh Welfare Association Croydon] moved to member Saad Ghazi’s Indian [sic] Cottage restaurant in London Road, West Croydon.” Note the discrepancy in naming here; however, the restaurant does appear to have been called India Cottage, as a photograph included in a planning application deposited on 7 May 1987, relating to numbers 73–77 next door (ref 87/1426/P), shows The India Cottage frontage at number 79. According to various articles in the Croydon Advertiser in the early 1990s, Saad Ghazi was also the proprietor of Jaipur Tandoori (see examples cited here).

Town Talk may not have been one of Mr Ghazi’s. A couple of planning applications from 1970, in relation to converting part of the first floor “to be used as kitchen in connection with existing use of ground floor as a restaurant”, are in the name of Rizwan Ul Hassan; who, of course, could also have been an agent or contractor (refs 70-20-1562 and 70-20-1734).

- A profile of Saad Ghazi on p15 of the 15 May 1991 Croydon Post (viewed as a photocopy in the biographical files at Croydon Local Studies) states that he was 47 at the time of the profile (hence born in 1943 or 1944), he was born “in Sylhet in what was then East Pakistan”, he “came to England in 1962” (i.e. at the age of 18 or 19), and he “was a co-founder of the Bangladeshi [sic] Welfare Association in 1984 and has been its unopposed General Secretary since”. (Note that according to their website, the correct name for the organisation is “Bangladesh Welfare Association”.) An article on p36 of the 26 February 2010 Croydon Advertiser states that in 1984 the Bangladesh Welfare Association Croydon moved its meetings to “member Saad Ghazi’s Indian [sic] Cottage restaurant in London Road, West Croydon.”

- An article in the 31 October 1990 Croydon Post states that Saad Ghazi’s “other restaurant” was the Khyber Pass at 552 London Road, Isleworth.

- Quotations taken from an advert on p17 of the 21 February 1992 Croydon Advertiser, viewed as a clipping in the firms files at Croydon Local Studies Library and Archive Service; this advert also stated that London Tandoori would be opening on 24 February 1992.

- London Tandoori is shown on the June 1992 and April 1993 Goad plans. Al-Amin is listed in the January 1995 and July 1996 Croydon phone books (as “Al-Amin Curry Hall”) and the June 1995 and May 1996 Goad plans. Akash is shown on Goad plans from May 1997 to September 1999 inclusive (as “Akash Tandoori”) and listed in the January 1998 and July 1999 Croydon phone books (as “Akesh [sic] Indian Restaurant”). Victoria Spice is listed in Croydon phone books from January 2001 to 2003–4 inclusive and Goad plans from June 2001 to May 2004 inclusive.

- According to a company director check, at least one of the Victoria Spice chefs was of Bangladeshi nationality; see, for example, Company Director Check and OpenCorporates, both of which list Abdul Muktadir, of Bangladeshi nationality, as company secretary and chef at Victoria Spice Limited, 79 London Road, from 25 April 2000. Company Director Check also states that this tenure ended on 2 December 2003, though this of course might apply only to the role of company secretary.

- A planning application from July 2004 states that the last known use of the premises was “Indian restaurant” from an “unknown” date to 24 March 2004 (ref 04-2183-P).

- Goad plans show “vac rest & und/altn” [vacant restaurant under alteration] in June 2005, Mantiana Cafe in May 2006, Ephesus f/fd rest [fast food restaurant] in July 2007, and Yasmin Cafe in August 2008 and August 2009. A planning application granted on 20 October 2005 (ref 05-3760-A) includes a drawing of proposed signage reading “Mantiana / Mediterranean Patiserie [sic] & Bakery”. (It’s worth mentioning that “patiserie” is the Romanian spelling of “patisserie”, which may give a clue as to the background of Mantiana’s owner, or it may just be a spelling mistake.) Yasmin Cafe can be seen on Google Street View imagery from July 2008, with “Cafe”, “Restaurant”, and “Lebanon’s [sic] & Middle Eastern Cuisine” on the sign, and pictures of shisha pipes in the window and on a projecting sign.

- Opening times and menu items taken from a takeaway menu collected in December 2011 (cover photo, interior photo). Note that “quozy” is a meal consisting of meat, vegetable/bean stews, and rice; see my article on number 72 for a photo of lamb quozy (also spelt “quzi”) from Bakhan, another Kurdish restaurant across the road. “Sade” (also spelt “sada”) is the same thing without the meat; just rice and stews. Kurdishness of Shameran confirmed by Justin Fores in the Chowhound posting quoted here.

- See London Road Roundup [London], dated 8 August 2010. The poster’s screen name is JFores, but I know his full name due to being a Chowhounder myself. I quote this with his permission (given via email, 9 October 2015).

- Opening date upper bound taken from the Chowhound thread referenced in the main text, dated 8 August 2010, in which it’s described as “Newly opened”. Closing date from personal observation; the last time I definitely saw Shameran open was in March 2012.

- Opening date of Shadi Market is from personal observation, as is the initial sale and later withdrawal of additional items; see my photo of some pickles bought at £4/kilo in July 2012. Google Street View concurs with my observation of the opening dates, showing the old Shameran sign in May 2012 and Shadi Market open and trading in July 2012.