Zodiac Court at 165 London Road was built in the 1960s on the site of Broad Green House, which itself dated back to the early 19th century. The development also incorporates Zodiac House at number 163 — office property rather than residential — and Timber Gardens restaurant at number 161.

Given this early origin, I’ve decided to cover the history of this site in a mini-series of three articles. Here, I discuss the Broad Green House estate up to the 1890s, when it was broken up for housing development; in part 2 I’ll continue the story of Broad Green House up to the end of its life in the early 1960s; and in part 3 I’ll describe the demolition of Broad Green House to make way for Zodiac Court, as well as happenings at Zodiac Court until the present day.

I’ll follow this with two more articles, one focusing on the site of Chatfield House, which was split off from Broad Green House during the 1890s estate breakup (this will also discuss Cinatra’s nightclub), and one covering the row of shops which was built on the Chatfield House site as part of the same development that created Zodiac Court.

1800s–1830s: Alexander and Elizabeth Caldcleugh

The earliest occupants of Broad Green House were probably Alexander Caldcleugh, his wife Elizabeth, and their children.[1] Alexander was lord of the Manor of the Rectory of Croydon, having purchased this Manor from the trustees of one Robert Harris after the latter died in September 1807.[2]

Alexander was living in London in 1795, but he had land at Broad Green by 1800, as the Inclosure map of that year shows him as owner of a plot near the junction of London Road and St James’s Road, roughly bounded by the modern-day Sumner Road, London Road, Chatfield Road, and Handcroft Road.[3]

As shown on the map extract above, this plot of land included a building of some kind. This may have been Broad Green House itself, or it may have been some other building that was later demolished; but in any case, Broad Green House was certainly in place by 1809.[5]

Alexander was a slave trader, acting both alone and in partnership with Edward Boyd and Joseph Reid under the firm Caldcleugh, Boyd, and Reid. He was responsible for at least 14 slaving voyages between 1797 and 1807, transporting nearly 4000 enslaved people, a tenth of whom died on the way. The last of these voyages, on a ship called the Croydon, departed from London on 21 April 1807, just a week and a half before the 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade came into force.[6]

Alexander Caldcleugh died “after a lingering illness” on 18 January 1809, at the age of 55, and was buried in the churchyard of Croydon Parish Church (now Croydon Minster) “in the space between the South side of the Church and the Footpath”. He left his estate in trust, with all profits, rents, and interest to be paid to Elizabeth throughout her lifetime. This money was intended both for her own maintenance and for that of their four younger children, including their only son, named Alexander like his father.[7]

1820s: Alexander Caldcleugh, junior

Born in 1795, Alexander junior was only 13 when his father died.[8] Although the Caldcleughs’ extensive wealth meant he had no need to earn money of his own, by the time Alexander reached his mid-twenties he had begun working for the British government. In September 1819, he travelled to Brazil as private secretary to “the Right Honourable Edward Thornton, Minister at the court of Rio de Janeiro”, and he remained in South America for the next three years.

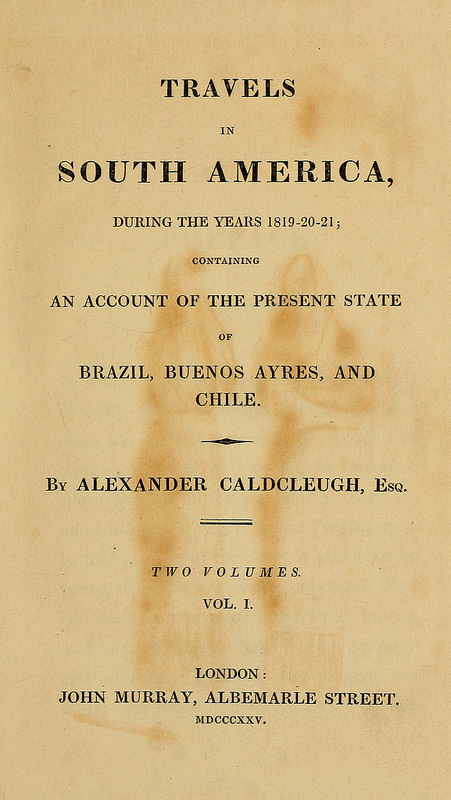

Alongside his government work, he not only collected plant specimens — the genus Caldcluvia is named after him — but also kept a diary which formed the basis of his published work Travels in South America, During the Years 1819–20–21, Containing an Account of the Present State of Brazil, Buenos Ayres, and Chile. He returned to England in November 1821, and lived at Broad Green House for most of the 1820s, before returning to South America in 1829 as a liquidation commissioner.[9]

By July 1834, he was living at Santiago, Chile, where he was recommended to Charles Darwin as a suitable acquaintance, being “a very accomplished chemist and mineralogist, as well as a most agreable [sic] well informed and obliging person.”[10] According to his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, his publications on South America “are regarded as some of the most important descriptive works” among the British writings of the period, containing “not only personal experiences, but also historic, geographic, statistical, and commercial information.” He died on 11 January 1858 at Valparaíso, Chile.[11]

Meanwhile, at Croydon, Elizabeth outlived her husband by a quarter of a century, dying on 8 February 1835 at the age of 67.[12] In accordance with Alexander’s will, the property that had previously been held in trust was then sold off, with the proceeds going to the younger generation of Caldcleughs.[13]

1830s-1840s: Jonathan Barrett

Broad Green House and its grounds were bought by Jonathan Barrett, an iron and brass foundryman who lived here with his wife Maria (and possibly also his nephew Jeremiah).[14]

Born to Quaker parents in the City of London on 26 June 1790, Jonathan was in his mid-40s when he arrived on London Road, and already on at least his second marriage. He must have been very well-to-do in order to afford Broad Green House, though it’s not clear how much of his wealth was due to his own work and how much came from his father, who was a foundryman before him.[16]

The family business — described variously as a foundry, a brass foundry, and a brass and bell foundry — was based in King’s Head Court, Beech Street, in the area of London now known as the Barbican. It’s unclear exactly when the foundry was first constructed, though a source from the early 1920s describes it as being “century-old” at that point. Certainly the family were living in King’s Head Court by 1793, as Jonathan’s younger brother Jeremiah was born there.[17]

Jonathan initially made moves to expand the Broad Green House estate; in April 1838, he bought an adjoining strip of land which had previously been part of Parsons Mead, and used it to extend his grounds further south. However, around 1844 or 1845 he carved out part of the northern side for a development which would eventually include nine houses between the remaining part of the estate and the junction with Sumner Road: four semi-detached pairs, and a slightly larger detached property. At least two of these houses were in place by July 1845.[18]

Jonathan and Maria continued to live here until Maria’s death at the age of 53 on 7 March 1847. On 30 May 1848, Broad Green House and its remaining grounds were offered for sale by auction at Garraway’s Coffee House in the City of London; by July of that year, Jonathan had moved to one of the newly-constructed properties to the north of Broad Green House, and his former home had a new occupier: John Dillon.[19]

1840s–1850s: John Dillon

Jonathan had spent just over a decade at Broad Green House, in contrast to the Caldcleughs’ four decades. John’s tenure was even shorter. His wife, Mary, died at home on 12 March 1856, and just three months later John sold Broad Green House for £7,000 (£691,800 in 2016 prices). The furniture was sold separately a month or so after that, along with other household accoutrements including “a clarence carriage [...], two handsome Alderney cows, rick of hay, store pigs, domestic poultry, iron garden roller and implements, greenhouse plants, [and] rustic garden seats and tables”.[20]

1850s–1890s: Charles and Mary Chatfield

The purchaser this time was Charles Chatfield, a landowner and fundholder who moved here from the High Street, bringing his wife Mary and daughter Adelaide with him. Born in Croydon around the turn of the century, Charles inherited the family wine and spirit business after his father’s death in 1821. By 1841, however, Charles had transferred the business to George Price, and was living on his (presumably fairly substantial) investments.[21]

The Chatfields’ move to Broad Green House was complete by November 1856. Over the next few decades, Charles and Mary became “very well known in the western part of Croydon” for their “benevolent and charitable” activities “in connection with Christ Church, and a variety of other useful works carried on at West Croydon.”[22]

The household expanded in May 1870, as Adelaide married Matthew Hodgson, son of the Vicar of Croydon, and brought him to live with her at Broad Green House. Their first child was born the following spring.[23]

Adelaide and Matthew’s wedding, which was one of the first to be conducted in the newly-restored Croydon Parish Church after its destruction in the fire of 1867, was attended not only by the invited guests but also by “two to three thousand” spectators outside. “About 80 ladies and gentlemen” were invited to the wedding breakfast at Broad Green House, after which the newlyweds departed for their honeymoon in North Wales via Leamington Spa.

The Croydon Advertiser reported at length on this “Fashionable wedding”:[24]

The bride’s dress was of white satin, trimmed with Brussels lace; the head dress being a simple wreath of Stephanotus and orange blossoms; for ornaments, a necklace, brooch, and bracelets of pearls, and the bouquet, a unique arrangement of orange blossoms, Stephanotus, white orchids, and ferns; while over all, a beautiful Brussels lace veil completely enveloped and almost hid the graceful form of the young bride.

Eleven charming bridesmaids [...] were dressed in white muslin over white silk, trimmed with green satin and lace; with tulle veils; each young lady wore a wreath of frosted Narcissus and ferns; and carried a bouquet of scarlet geraniums, Stephanotus, and white camellias [...] Each bridesmaid wore a gold locket with the bride’s initial letter “A.,” in pearls and red coral. The lockets contained the photographs of the bride and bridegroom. [...]

At 11.30 the ceremony was impressively performed by the bridegroom’s father and grandfather. The last word of the service had scarce been uttered by the venerable clergyman, when Mendelssohn’s grand Wedding March burst forth as if by magic from the organ, as the bridal party proceeded to the vestry to sign the marriage register. This being accomplished, the bridal procession passed down the nave, the music being changed to Meyerbeer’s Marche du Sacre, from “Le Prophete.”

Charles died at home on 23 November 1876, at the age of 77, and was buried in the churchyard of Croydon Parish Church, like Alexander and Elizabeth Caldcleugh before him. Adelaide and Matthew moved out of Broad Green House around this time, too, and by 1878 were living on Wickham Road in Shirley.[26]

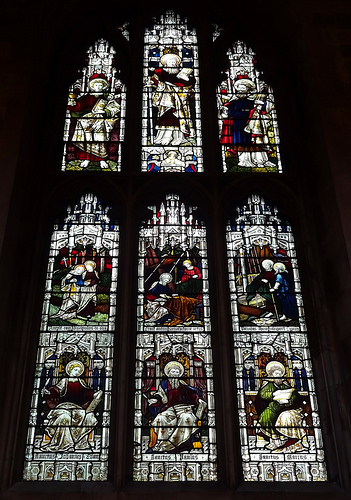

Mary outlasted Charles by 15 years, dying on 30 August 1891 at the age of 88. A couple of years after her mother’s death, Adelaide and “a few near relatives” paid for a new stained glass window to be installed in the Parish Church in Charles’ and Mary’s memory.[27]

Mary’s death proved to be a turning point in the history of the Broad Green House estate. Although the house itself would survive for a further 70 years, the grounds were rapidly sold off and built on, with new roads — including one named after the Chatfields — laid out and lined with housing. In part 2 of this mini-series, I’ll describe events at Broad Green House over the succeeding years, and in part 3, I’ll cover the demolition of Broad Green House to make way for Zodiac Court, and happenings at Zodiac Court up to the present day.

Thanks to: Carole Roberts; Michael Richards; Peter Sturge; Rachel Lang at the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership; Ray Wheeler; Sean Creighton; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers Bec, Damerell, and Kat. Census data consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

- Family historian Michael Richards, whose wife Rosemary is descended from Alexander Caldcleugh, tells me that the correct pronunciation of “Caldcleugh” is “Call-clue” — that is, the “d” is silent, and the second syllable is pronounced “clue” rather than “cluff”. This was passed down through the family; Rosemary’s mother was taught to pronounce it by Rosemary’s grandmother Ermine, and Ermine was taught by Rosemary’s great-grandmother, who was Alexander’s great-grandchild.

Information on Alexander’s purchase from Robert Harris’ trustees is taken from The History and Antiquities of the County of Surrey by Owen Manning and William Bray, 1809, Volume 2, page 541, which also lists many previous owners of this Manor. The only source Manning and Bray give for this is “Much of this is from the obliging information of Mr. Drummond.”

In his Plan and Award Of the Commissioners appointed to Inclose the Commons of Croydon (1889), J Corbet Anderson adds that: “In the Croydon Inclosure Act of 1797, Robert Harris, Esq., is described as lord of the Manor of the Rectory of Croydon otherwise Bermondsey within the said parish. After the decease of Mr. Harris in 1807, the Chancel of the Old Church [i.e. Croydon Parish Church, now Croydon Minster] and the Rectory Manor-House at North End were purchased by Alexander Caldcleugh, Esq.; and his successor, also named Alexander Caldcleugh, was lord of the Manor of the Rectory of Croydon when Parson’s Mead was Inclosed in 1823” (footnote, p137). For more on the Inclosure of Parson’s Mead, see my article on 145 London Road.

Corbet Anderson also describes the extent of this Manor: “from opposite the ‘Half Moon,’ at Broad Green, down the west side of the main road to ‘Crown’ corner; then down Crown Hill into Church Street; when, turning to the right past the ‘Derby Arms,’ it reached back again to the ‘Half Moon.’” (footnote, p26). The “main road” referred to here is of course London Road and North End, while “‘Crown’ corner” is the junction of North End and Crown Hill, where the Crown Hotel once stood. The Half Moon has also now been demolished, while the Derby Arms has been converted to residential use.

It should be noted that the word “lord” here refers not to nobility (earls, dukes, etc) but to an association with a particular piece or pieces of land. The lordship of a manor originally came along with ownership of land and/or rights over land, but the title itself could be sold just as a piece of land could be sold (and indeed could be sold without also selling the associated land or rights). “Lord of the Manor” was not a hereditary title, and there was no requirement for the owner of the title to be of noble birth.

- Alexander’s son, also named Alexander, has an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which states that he was born in London in 1795 and baptised at St Olave’s, Hart Street; this suggests that his parents were living in London at the time.

- This is a scan of a photocopy of the map included in Corbet Anderson’s Inclosure book; I have removed some of the creases in it too. Note that these plots were already in Alexander’s possession at the time the map was made. According to page 137 of the book, the Inclosure commissioners awarded him some additional land, a “parcel of waste land on Croydon Common containing twenty-four perches” (plot 592, right at the top right corner of the map excerpt here), “in lieu of his Right of Common for and in respect of his messuage lands and tythes”. I have matched this map to modern-day roads by overlaying it with Toner Lite map tiles by Stamen Design, under Creative Commons cc-by (retrieved 25 November 2012).

I haven’t yet managed to find out when Broad Green House was constructed. As noted in the main article, there was a building on the site by 1800, but its shape doesn’t clearly correspond to that of Broad Green House on later maps. John Roque’s 1768 map of Surrey also shows a building on this site, but this has a different shape from both the one on the 1800 Inclosure map and later maps showing Broad Green House. (It should be noted that these early maps weren’t necessarily all that accurate about the exact shapes or positions of buildings.) The earliest evidence I’ve found of the Caldcleughs actually living in Croydon relates to 1809, being a transcription in Corbet Anderson’s Inclosure book of “a handsome marble tablet” on “the North Wall of Chancel” in the old (pre-fire) Parish Church: “In the family Vault in this Chancel are interred the remains of Alexander Caldcleugh, Esq., of Broad Green House, near Croydon, who departed this life on the 18th day of January, 1809, aged 55 years.”

In his Images of England: Norbury, Thornton Heath and Broad Green, Raymond Wheeler states that Broad Green House was built in 1807. However, he tells me that he can’t remember his source for this, as it was a while ago that he conducted this research; he suggested it could have been from sales particulars or from Aileen Turner’s unpublished History of Broad Green (via email, 15 May 2017), but neither he nor I can find it in the latter source now. According to a letter published on page 8 of the 13 January 1956 Croydon Advertiser, Kenneth Ryde, who was then Croydon‘s Chief Reference Librarian, believed it to have been “built by Alexander Caldcleugh, probably at the close of the 18th century”, though again no sources are given. According to an article on page 22 of the 9 November 1956 Croydon Advertiser (“New name for Gregg School”), building works during the 1950s uncovered artifacts including “An 1815 ‘smoke jack’ — a machine for turning a roasting-spit by using the current of hot air in a chimney — [and] a bell of 1729”. (The author of the article claims this as proof that the building dated from the 1720s, but it seems unlikely.)

- Information on Alexander’s slaving voyages is taken from The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (accessed on 26 June 2017). This database has 14 hits for voyages in a vessel owned by “Caldcleugh”, all departing from London between 14 December 1797 and 21 April 1807. Alexander’s first name is only given in one instance (an 1805 voyage in a ship named the Ariel), but “Caldcleugh” has a co-owner of “Boyd” (either Edward or William) in five other voyages (including that of the Croydon), and it does seem unlikely that there were two slave traders called Caldcleugh operating from London at the same time. The dissolution of Caldcleugh, Boyd, and Reid is recorded in a notice on page 1925 of the 24 September 1814 London Gazette. Joseph Reid was Alexander’s son-in-law (see next footnote). The text of the 1807 Act is available on the William Loney RN website (a family history website).

- The quotation about Alexander’s illness is taken from his death announcement on page 4 of the 19 January 1809 Morning Post. His age at death, date of death, and place of burial (including quotation about specific location) are taken from Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past, a record of inscriptions on the memorial stones, headstones, and other monuments of Croydon’s graveyards as of 1883. Details of his last will and testament are taken from my own transcription of the probate register copy. I have simplified this slightly — the part of the estate left in trust was the part remaining after paying his “just Debts and Funeral Expences [sic]”, transferring £1000 of the capital in his business to his son-in-law and business partner Joseph Reid, devising his freehold estate in Scotland to his son Alexander, and giving £20 to his other business partner, Edward Boyd, as a “token of my esteem”. The trustees were Elizabeth herself, the abovementioned Joseph Reid, William Borradaile, and Thomas Reid. The Caldcleughs had five children at the time Alexander made his will — Mary Ann, Margaret Trenham, Elizabeth, Alexander, and Helen — but Mary Ann was already married to Joseph Reid, and hence presumably wasn’t in need of maintenance.

- Alexander junior’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that he was born on 17 June 1795, making him 13 when his father died on 18 January 1809.

- Travels in South America was published in two volumes, both of which are available at the Internet Archive: volume 1, volume 2.

- Letter from H S Fox to Charles Darwin, dated 25 July 1834 from Rio de Janeiro, quoted as letter DAR 204.8 in The Correspondence of Charles Darwin: 1821-1836, Volume 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1985). I don’t know for definite whether “agreable” is how Fox spelled this word, or whether it’s a misprint in the reproduction (which is typeset, not facsimile), but the “Editorial policy” section of the book states that “Misspellings have been preserved even when it is clear that they were unintentional”, so it is likely Fox’s own spelling. The beginning of the quoted sentence is: “At St. Iago de Chili, you will of course become acquainted with Mr: Caldcleugh, who is residing there, whom you will find a very accomplished [...]”. Although this source uses the name “St. Iago de Chili”, this is clearly just the contemporary name for Santiago; a letter around the same time from Darwin to his sister Caroline includes the sentence: “I now struck down to the South, to St Iago the gay Capital of Chili.” (dated 13 October 1834 from Valparaiso, letter DAR 223 in the same source as above).

- A death notice on page 6 of the 30 March 1858 Sussex Advertiser reads: “On the 11th Jan. last, at Valparaiso, Chile, Alex. Caldcleugh, Esq., late of Broad Green, near Croydon, Surrey.”; this notice also appears on the front page of the 23 March 1858 Times.

- Elizabeth’s age at death and date of death are again taken from Croydon In The Past, which unsurprisingly also records that she was buried in the same place as her husband. Her death notice on page 8 of the 15 February 1835 John Bull confirms that she died at Broad Green House.

Details of Alexander’s will are again taken from my transcription. The will states that “from and immediately after the decease of my said wife (or upon her second Marriage or at any time previous thereto if my said trustees or trustee shall think [fit]”, the property should be sold off, and the proceeds invested “in some or one of the public Stocks or Funds or upon Government or real Securities at Interest”. These investments and “all the residue” of his “personal Estate” would then be divided among the five children. The daughters would receive their share when they married or reached the age of 21 (except for Mary Ann Reid, who was already married at that point and would get hers immediately), and Alexander would receive his when he reached the age of 25.

The Croydon parts of this property included not only Broad Green House itself, with its extensive grounds, but also Parsons Mead, a large area of previously-common land that had been assigned to Alexander’s trustees following the Parsons Mead Inclosure Act of 1923. Parsons Mead was divided into several lots before being sold, and these lots were in the main bought by different people, and developed at different times. Over the next several decades, numbers 1–151 London Road slowly rose up, bit by bit, along the main road frontage.

See my article on 151 London Road for the source of my information on Jonathan’s occupation. His first appearance in the rate books is in the October 1835 Church Rate Book, where the column for “Landlords Lessees or Owners Rated” lists “Barrett or Occupier”, perhaps indicating that he hadn’t quite moved in yet. Maria’s name is taken from her death announcement on page 4 of the 10 March 1847 Evening Standard, which describes her as being “wife of Jonathan Barrett, of Broad-green House, Croydon”.

Regarding Jeremiah, although Jonathan and Maria are absent from the relevant part of the 1841 census (Croydon civil parish, enumeration district 9), there is a household consisting of 15–19-year-old apprentice engineer Jeremiah Barrett, 30–34-year-old Ellen Keen, and two servants. Jonathan’s brother Jeremiah (see later footnote) had a son, also called Jeremiah, born on 19 December 1823 (see his birth record in the Quakers’ Quarterly Meeting of London and Middlesex register of births), which would have made him 17 at the time of the census. Moreover, Jonathan married an Ellen Keen of the right age after Maria’s death (Ellen will be discussed further in a future article). It therefore seems possible that Jeremiah was living at Broad Green House, Jonathan and Maria were away visiting friends on the census night, and Ellen Keen was a friend or relative who was either permanently residing with the family or staying temporarily to keep an eye on Jeremiah. (Regarding ages, note that the 1841 census instructions state that those aged 15 or above should have their ages rounded down to the nearest multiple of 5, though “the exact age may be stated if the person prefers it”. Jeremiah’s age is given as 15 and Ellen’s as 30.)

- Peter tells me that the provenance of this portrait is unknown. He also notes that it was unusual for Quakers at this time to have their portraits made, as portraiture was considered to be a sign of vanity and worldliness. This image has been slightly edited from Peter’s version in that I have straightened it and removed a reddish colour cast that seemed more likely to have been added by the camera than by age.

Jonathan’s date and place of birth are taken from his birth record in the Quakers’ Quarterly Meeting of London and Middlesex register of births, which describes his father John as a “Citizen & Founder”. Specifically, his place of birth is “Little Moorfields in the Parish called St Giles, Cripplegate Without in the limits of the City of London”; according to Bruce’s Lists of London Street Name Changes, Little Moorfields was the street now known as Moorfields.

John Barrett’s Quaker death record states that he died at Plaistow on 30 December 1829 and was buried in Bunhill Fields. The foundry is not explicitly mentioned in his will (PROB 11/1765/50), which is dated 8 December 1827, but after bequeathing several houses at Plaistow, cash amounts, and annuities to various family members, he leaves the remainder of his estate to his three sons Richard, Jonathan, and Jeremiah “as tenants in common”.

Regarding Jonathan being on at least his second marriage, before marrying Maria he married Mary Maggs on 3 June 1812 (see their Quaker marriage record).

Jeremiah’s birth record in the Quakers’ Quarterly Meeting of London and Middlesex register of births states that he was born on 22 December 1793 at King’s Head Court, Beech Street, St Giles Cripplegate Without. This Jeremiah was the father of the previously-mentioned Jeremiah, nephew of Jonathan, who appears at Broad Green House in the 1841 census. Description of the family business as a brass and bell foundry comes from the Quaker marriage record of Jonathan and Jeremiah’s older brother Richard, who is stated there to be a “Brass & Bell Founder” of “Kings head Court Beech Street London” and the son of “John Barrett of same place Brass and Bell Hounder”.

John James Baddeley’s Cripplegate, published in 1921 (PDF), describes a bomb dropped in June 1917 “which fell in the open yard of King's Head Court, on the north side of Beech Street, around which were the extensive century-old premises of Messrs. Barrett & Sons, brass founders. These premises covered an area of 190 ft. by 90 ft., and were occupied by the foundry, workshops and offices” (page 315). This foundry is almost certainly the one marked as “Foundry (Brass & Iron)” on OS 1896 London Sheet VII.55.

See my article on 151 London Road for more information on the strip of Parsons Mead land. The Tithe Award map of 1844 shows Jonathan as both owner and occupier of all the land up to Sumner Road, but the July 1845 Poor Rate Book shows two additional properties between Broad Green House and Sumner Road. Although the rate books don’t include detailed addresses, and also don’t always list people in the right order when going along a road, in this case it’s possible to follow the properties back from 1851 (for which year there is a detailed printed street directory), matching them from year to year via the occupants, landlords, and rates charged or estimated rentals (from which the rates were calculated).

This procedure suggests that there were at least two houses by July 1845, at least six houses by April 1848 (which matches well with the May 1848 plan shown here), at least eight houses by April 1850, and all nine houses by November 1850. The configuration of the houses as four semi-detached pairs and a larger detached property is taken from the 1868 Ordnance Survey map (Surrey Sheet 14.6), and corresponds well to their estimated rental values in the November 1850 Poor Rate Book (eight at £50 and one at £84, or £6,177 and £10,377 respectively in 2016 prices). I’ll discuss these houses at greater length in a future article.

- Maria’s age and date of death are taken from an announcement on page 4 of the 10 March 1847 Evening Standard. Date and place of Broad Green House auction are taken from sales particulars in the Harold Williams volumes at the Museum of Croydon (volume 1845–1848, number CCXLVII). These particulars give the extent of the grounds as 5 acres, 3 rods, and 17 perches, and the accompanying plan (reproduced here) shows clearly how the northern side of the estate has been separated off for housing. The October 1848 Poor Rate Book lists J Dillon at Broad Green House, and “Jon” Barrett in a much more modest house nearby (the rateable value of Broad Green House is given as £147, and that of Jonathan Barrett’s new home as only £50); notations next to their names make it clear that the changeover happened in July.

Date and place of Mary’s death are taken from her death announcement on page 7 of the 18 March 1856 Sussex Advertiser. Sale price of Broad Green House is taken from a report on page 7 of the 18 July 1856 Morning Advertiser, which gives the date of the sale as 16 July 1856 and the place of the sale (by auction) as “Garraway’s”, presumably the same Garraway’s Coffee House at which Jonathan Barrett divested himself of the house eight years before. Information on sale of furniture (and quotation) is taken from an announcement on page 8 of the 12 August 1856 Morning Advertiser.

I haven’t been able to find out much about John and Mary themselves, partly because they were away from home on the night of the 1851 census, leaving Broad Green House in charge of a servant named Thomas Knight.

Charles’ date and place of birth are taken from various censuses. Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past states on page 40 that “Mr. Charles Chatfield was formerly a wine merchant, in High Street (now G. Price & Son), and resided for many years at Broad Green House, London Road.” According to John Corbet Anderson’s Croydon Inclosure 1793–1803 (footnote on page 123), Charles’ father, “William Chatfield, Esq., was brother to the before-named [i.e. also mentioned in the Inclosure Award] Robert Chatfield, Esq., and they were partners in the old-established Wine and Spirit business now owned by George Price and Son.” William’s date of death is taken from Croydon In The Past.

The 1841 census records George Price as a wine merchant on the High Street, and Charles Chatfield, also on the High Street, living on independent means. The 1851 census, which unlike the 1841 census gives addresses, records George Price as a wine and spirit merchant at 114 High Street and Charles Chatfield as a “Landed Proprietor &c” next door at number 113. According to Carole Roberts, who has made a special study of the High Street, these properties were “on the West side next to where Whitgift Street is now, being large plots with substantial gardens”; 113 was renumbered to the present 76–78 and 114 to the present 72–74 between 1885 and 1886 (via email, 31 May 2017 and 14 June 2017).

The Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project at University College London speculates that Charles Chatfield of Croydon may have been the Charles Chatfield who, as trustee of Matthew Gregory “Monk” Lewis, was awarded part of the slavery abolition “compensation” for the Cornwall estate in Westmoreland, Jamaica. However, this speculation is accompanied by a statement that the trustee Charles Chatfield was “very probably” someone else.

- Rate books show Charles Chatfield at 113 High Street up to and including 1855 (information provided by Carole Roberts) and on London Road from the November 1856 Poor Rate Book onwards (information from my own research). He also appears on London Road in street directories from Gray & Warren’s 1859 onwards. (Gray & Warren’s 1855 directory places him at 113 High Street.) Quotations are taken from a Croydon Advertiser column published shortly after Mary’s death (“Argus Letters”, 12 September 1891, page 5). Given that Mary left assets totalling around £31,000 (£3.6m in 2016 prices), one can imagine she was very well able to afford to be charitable (see her entry in the National Probate Calendar).

- The 1871 census (conducted on the night of 2/3 April) shows Adelaide and Matthew living at Broad Green House along with Adelaide’s parents and a one-month-old “Infant Hodgson”. This infant appears not to have survived, as the Hodgsons’ oldest child in the 1881 census is only 7.

A report in the Croydon Chronicle (“Fashionable wedding”, 7 May 1870) states that “Although a few weddings have been solemnized, it was the first one of the kind which the ‘Old Church,’ in its restored splendour has been called upon to celebrate”, which is a little difficult to understand, but I take to mean that this was not only one of the first weddings in the restored church but also the grandest. For more information on the 1867 fire, see John Hickman’s Croydon Advertiser article or Brian Lancaster’s Consumed by Fire: The Destruction of Croydon Parish Church in 1867 and its Rebuild.

The quotations regarding the number of spectators and number of wedding breakfast invitees are taken from the Croydon Chronicle report. The longer quotation about the bride and bridesmaids is taken from a similar report in the Croydon Advertiser (“Fashionable wedding”, 7 May 1870, page 2); this is also the source of information on Adelaide and Matthew’s honeymoon (“wedding tour”) destination.

- The window is in the north wall of the minster, next to one dedicated to Thomas Edridge. According to an article on page 2 of the 8 April 1893 Surrey Mirror, the Chatfield window and the Edridge window were both proposed and approved at the Croydon Vestry meeting of 4 April 1893. The plaque beneath reads: “To the Glory of God, and in loving memory of Charles, and Mary Chatfield, this Window is dedicated by their only daughter, and surviving child, Adelaide Mary Hodgson, and a few near relatives. A.D. 1893.”

- Charles’ date and place of death are given in his entry in the National Probate Calendar. His age at death and place of burial are taken from Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past (page 40). Matthew and Adelaide Hodgson are listed at Shirley Cottage, Wickham Road, in the 1881 census, and Matthew also appears there in Atwood’s 1878, Worth’s 1878, Ward’s 1878, and Ward’s 1880 directories (and possibly later ones too — I haven’t checked to see how long they stayed there). Ward’s 1874 and 1876 directories don’t list Shirley addresses, so I don’t know whether the Hodgsons moved out of Broad Green House before or after Charles Chatfield died.

- Mary’s age and date of death are taken from an announcement on page 4 of the 5 September 1891 Croydon Chronicle. The memorial window is shown here; see its footnote for more information on the dedication.