Vistec House at 185 London Road is currently in the process of being converted from a vacant office block into flats. It was built in the 1960s on the site of what was once a semi-detached pair of houses.

Here I describe the construction of these houses and the occupants of the southernmost one up until the point when its last residential users departed. In my next article I’ll discuss the occupants of the other house up to the same point, and in a concluding article I’ll cover the later non-residential users, the demolition of both houses, and the construction and history of Vistec House.

1840s: Construction of the original buildings

The original buildings were constructed on land that had previously been part of the grounds of Broad Green House, a “handsome brick edifice” set in several acres of estate which at the time was occupied by iron and brass foundryman Jonathan Barrett and his wife Maria. Around 1844–1845, Jonathan divided off the northern part of his estate for the construction of nine new houses, all fronting on London Road. The present article is concerned with the southernmost of these houses, originally 54 London Road but later renumbered to 105 and then to 185, while the others will be covered in future articles.

At least two of the new houses were in place by July 1845, and construction was complete by November 1850, comprising four semi-detached pairs and a larger detached property which stretched from the northern edge of the Broad Green House estate to the junction with Sumner Road.

Maria Barrett died on 7 March 1847 at the age of only 53. Within a couple of months of her death, Jonathan had sold Broad Green House and its remaining grounds and moved into the recently-constructed semi-detached house next door: 185 London Road.[1]

1840s: The earliest occupants

Jonathan was not the first resident of this new house. He was preceded by John Reid, who himself was possibly preceded by August, Augusta, or Augustus de Wilde — although that person may in fact have lived next door at number 187.[2]

1840s–1880s: Jonathan and Ellen Barrett

Nevertheless, the now-widowed Jonathan Barrett was living at 185 London Road by July 1847. He did not remain a widower for long, however, as on 13 November 1850 he married Ellen Keen. Ellen was two decades younger than Jonathan, and seems to have been associated with his family for some time; she may even have been a relative of some kind.[3]

Jonathan seems not to have taken a prominent part in the public life of Croydon, but one act of his did have a lasting effect on that part of the area known as Broad Green. In July 1859, a “memorial” signed by “a number of inhabitants” was presented to the recently-formed Croydon Local Board of Health requesting the erection of a public drinking fountain “in the High Street, near Mr. Stevenson’s corner”. Mr Stevenson, however, objected to this, stating that “there was not sufficient room, [...] the footpath would be continually obstructed, [...] in frosty weather it would be exceedingly dangerous, from the overflow and waste”, and that it would be “a very great nuisance [...] to have boys and others always round my windows.”[4]

Given this pushback, the Board must have been quite grateful for Jonathan’s writing to them to offer £30 towards the expense of “a handsome drinking fountain, and a drinking place for horses and dogs” at “the junction of the cross-roads at Broad-green, which was a great thoroughfare, very much used by the public.” This “very generous offer” was accepted, as was Jonathan’s later offer to increase his donation to cover the full cost of £35 10s charged by the contractors (£4381 in 2018 prices).[5]

The fountain was erected in the summer of 1860, but Jonathan did not live to see it; he was away at Hastings at the time, and died there on 3 July at the age of 70.

This spared him some disappointment, as the execution of his idea seems to have been less than successful. In addition to design flaws in the fountain itself, it soon became clear that the water supply was inadequate. Board member Alfred Carpenter reported to his colleagues at a meeting on 17 July 1860 that when passing the fountain the previous Sunday he had noted that it “ran over and made a slop”, and “ran so slowly that it would take two minutes to fill a tumbler”. Other Board members agreed:[6]

The Chairman — [...] the basin is always running or dripping over. The shape of the marble basin is a semi-circle, with a rim that inclines outwards instead of inwards, and consequently any water that splashes on to it runs over and makes the approach wet.

Mr. Crowley — I think it a great pity that the base was not arranged better than it is. The paving is on a level with the road, and the ground on each side of the fountain raised, so that the fountain seems sunk instead of raised. [...]

Dr. Carpenter — I think the erection would look better if the top was knocked off. (Laughter.)

Ellen continued to live in the house she had shared with Jonathan until her own death on 28 November 1880 — like her husband, at the age of 70. She was buried in Queen’s Road Cemetery.[7]

1880s–1890s: Thomas Henry Barnes

The next occupant was Thomas Henry Barnes, a physician and surgeon who moved here from St James’s Road in 1881 along with his wife Mary Anne. Thomas was a medical officer for the Croydon Union, a body formed in 1836 for purposes including the provision of health care to people unable to pay for it themselves.[8]

He also worked as a surgeon for the Croydon Provident Dispensary on Katharine Street.[9] This dispensary was one of the earliest branches of the Metropolitan Provident Medical Association, an institution founded in 1881 with the aim of setting up “self-governing and self-supporting dispensaries over the whole area of the metropolis”. Each dispensary had the services of “a medical staff of respectable medical practitioners resident in its neighbourhood, who receive[d] a fixed proportion of its income.” There was no charitable input; all income was “provided by regular monthly contributions of the benefiting members”. It was a form of insurance, whereby paying this monthly fee would allow people to see a doctor, dentist, or midwife when needed and be prescribed medicine at no extra cost.[10]

At this time, decades before the National Health Service, most medical care was either privately paid for by the individual patient, provided to paupers by institutions such as the abovementioned Croydon Union, or funded by benevolence: via charitable donations, bequests, or voluntary subscriptions paid by rich people to support hospitals such as Croydon General Hospital. Indeed, at the inaugural meeting of the Croydon Provident Dispensary in October 1881, Dr Alfred Carpenter described a lack of opportunity for benevolence as one of the objections he had heard to the establishment of such dispensaries:[11]

“Benevolent men have said, ‘If we are going to make everyone provide for his own doctor, what becomes of the letters to the hospital? We shall have no opportunity of extending our benevolence to enable Smith or Jones to get medical relief without any expense to themselves.’ I have very strong opinions on the subject of benevolent medical relief. Any benevolence which leads people to expect this or that from some persons, who may after all fail to give it to them, and which leads them to expect that everything will turn out right for them without their taking any trouble in the matter, is doing a very serious harm to the individual entertaining such ideas. [...] Benevolence has done an immense amount of harm in this country by being wrongfully employed; and in no way has it done more harm than in this mode of benevolent medical advice.”

Thomas continued to work at the Croydon Provident Dispensary until he left Croydon for Bayswater around 1894.[12]

The Croydon Provident Dispensary remained in existence until at least 1914. However, the National Insurance Act of 1911, which mandated compulsory enrollment of all manual workers as well as all other workers earning under £160 per year (£18,513 in 2018 prices) in a new national insurance scheme, led to the loss of 600 dispensary members — along with their financial contributions. The management committee reported at an extraordinary general meeting in July 1913 that “having carefully considered its present financial position and prospects”, it recommended that “if financial support was not forthcoming in the course of a short period the dispensary should be closed.” By 1916, all mention of it had vanished from the Medical Directory.[13]

1890s: Reverend Stephen Ray Eddy

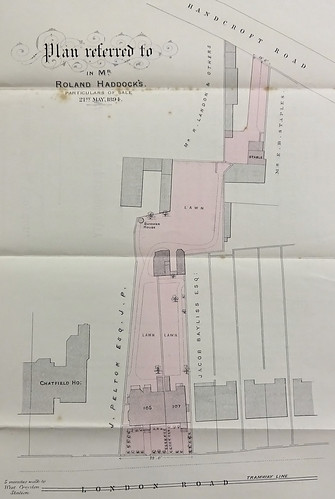

On 21 May 1894, the freehold of Thomas’ recently vacated house was put up for auction at Roland Haddock’s sale rooms on North End. The sales particulars give a thorough description of 185 London Road at this time:[14]

Entry to the house was via “a Tile-paved Path” and “Portland Stone Steps to Recessed Entrance”. On the ground floor was a “Study or Consulting Room with Tiled Abbotsford Stove, Folding Shutters to Windows, [and] Lavatory Basin in Cupboard” — almost certainly where Thomas used to see his private patients — as well as a drawing room with a “Tiled Stove and Hearth” and “Marble Mantel”, a dining room with a “Steel Stove” and “Black Marble Mantel”, and a morning room.

There were four bedrooms on the first floor, and above that “Two Attics with Cupboard in each, one with Stove” for the servants. The “light Basement” comprised a “good Front Kitchen with 2-oven Range and Hot-water Drawer off tap”, a “Large Back Kitchen with Oven and Boiler Range”, a “Scullery with Pump [and] Taps for hot and cold Water over Sink”, a coal cellar, a wine cellar, and a larder.

The grounds of the property were quite extensive, stretching all the way back to Handcroft Road. They included two lawns (one “with Flower Border” and the other “well-enclosed [...] for tennis, with large Fruit Trees on Walls and Roses &c., in Border”), a “Semi-circular vinery having 5 young Vines in bearing”, a “lean-to Greenhouse”, a “Stoke House with Furnace and Pipes for heating the Vinery and Greenhouse”, and a “Summer House with Rockery at sides”.

There was also an “Enclosed Yard with Brick, Cemented, and Slated Coach House, Harness Room, and Stable with Two Stalls”, as well as a “space in front for washing Carriages” (which, like the stable, was “paved with Staffordshire Bricks”) and a “Cemented Manure Pit”. This stabling area was accessed via Handcroft Road.

The lucky beneficiaries of all this were the Reverend Stephen Ray Eddy and his wife Lucy. Born on 13 February 1831 in Mold, Flintshire, Stephen gained his BA and MA from Christ’s College, Cambridge, and was ordained as a deacon in 1858 and a priest in 1859. He then served as vicar and rector in Derbyshire and Lancashire, but seems to have retired from the church around 1889. Stephen and Lucy arrived on London Road in 1894 and remained for around three or four years before moving to Reigate, where Stephen died on 15 July 1898.[15]

1890s–1920s: Victor, Rose, and Dorothy Vervaeke

Next to arrive at number 185 were Victor and Rose Vervaeke, along with their daughter Dorothy. Victor, who was a horse dealer, may have chosen the house partly for its well-situated stables, though his actual business premises were further north at Thornton Heath Pond, just off London Road on a side street called Willett Road. Born in Belgium in the early 1860s, he was either living in or visiting Croydon by 1881, when the census records him on Tamworth Road in the household of his half-brother Edward Gryspeerdt.[17]

Victor and Rose married at Croydon Parish Church (now Croydon Minster) on 5 March 1889, and were living on Lansdowne Road by the end of the year. They moved to London Road around 1897, at which point Rose was in her late 20s, Victor in his early 30s, and Dorothy around 5. Dorothy married in 1918, but her parents continued to live at 185 London Road until Victor’s death on 30 September 1922.[18]

Rose remained at 185 London Road for a short while after Victor’s death, but was gone by the end of 1923. Either at this point or some time later she moved in with her daughter Dorothy and son-in-law Arnold. It’s unclear where the younger couple had begun their married life, but by 1925 they were living in Abbotsbury, a house at the corner of London Road and Chatsworth Road just a hundred metres south of number 185. Rose died at Abbotsbury on 22 May 1955, leaving effects of £10737 12s 6d (£277,000 in 2018 prices).[19]

1920s: Brian Seamer Allen

Rose Vervaeke was replaced at 185 London Road by Brian Seamer Allen and his wife Kathleen Margaret. Born the son of a bank clerk in Lewisham in 1899, Brian attended Lord Weymouth’s Grammar School in Warminster and served as a pilot in World War I before marrying Kathleen in Spring 1921.[20]

Brian and Kathleen arrived at number 185 around 1923, and remained here for about five years before moving to Oakfield Road, a side road off London Road a short distance to the south.[21]

Brian was a co-founder of the Allen-Bennett Motor Company, which began life around 1919 at 230 London Road, almost directly across the road from number 185. I’ll discuss that business, as well as Brian’s other career as a pilot, in the relevant article.[22]

1920s–1930s: Crouchers, a Chandler, and a Sturt

The late 1920s and early 1930s saw the house at 185 London Road occupied by Robert and Edith Croucher, Mary Chandler, and Mary Ann Sturt. It’s unclear exactly what the relationship between them was, though it seems likely that Robert and Edith were married to each other. Robert, Edith, and Mary Ann were in place by 1929, and Mary Chandler arrived by 1930, but all were gone again by 1934.[23]

1930s–1940s: Albert and Rose Handscomb

185 London Road was now nearly a century old, and for most of that time had been home to relatively well-to-do families. The next occupants, however, were rather lower on the social scale.

Albert Victor Eaton Handscomb was born in Wandsworth in 1888. His father was a carman; that is, the driver of a horse-drawn cart, while Albert’s own occupations included barman, builders’ labourer, and bus conductor. Albert’s wife Rose, four years younger than him, contributed to the family income by turning their home at 185 London Road into a lodging house.[24]

The Handscombs were in place by October 1935, and by September 1939 the household consisted of Albert, Rose, at least one and probably all of their four children, and six lodgers.[25]

The youngest of these lodgers, Margaret Plowman, worked in a factory as a driller, making sheet metal components for aircraft. She had been living in Croydon for only ten weeks when she was brought up before the Borough Bench accused of stealing £28 (£1,798 in 2018 prices) from her landlady Rose’s handbag. Margaret admitted to the theft, and returned the remaining money, but said she had already spent around half of it on “clothes and other articles” in the West End. She “pleaded for an opportunity to return to her parents in Derbyshire”, whom she had left “because of a quarrel with her father, who objected to her going out with boys, and coming home late at night.” The magistrates remanded her on bail “with a view to arrangements being made”.[26]

The Handscombs were likely the last people to make use of number 185 as a residence. Although it’s unclear exactly how long they stayed, by late 1946 they had all departed and number 185 was occupied by shopfitting firm Marvin Hart. The story of Marvin Hart, and the final demolition of the building, will be told in a future article.[27]

Thanks to: the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the Wellcome Library; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-reader Ian. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

Quotation regarding Broad Green House is taken from an advert for its sale on page 8 of the 17 May 1848 Morning Chronicle. This advert describes the estate as “embracing in the whole nearly six acres” (and note that this is after the northern part was separated off for new housing). See my article on Broad Green House for more information, including evidence on the assertions in this and the preceding paragraphs. Gray’s 1851 directory lists Jonathan Barrett at 54 London Road (later renumbered to 105 and then 185), but he appears in rate books prior to this (see abovelinked article for more details). For evidence that the semi-detached pair originally numbered 54 and 55 London Road were the site of Vistec House, see side-by-side comparison on the National Library of Scotland website.

Gray’s 1851 directory also gives alternate addresses for the nine houses: 1–9 Broad Green Place. This is a little odd, since there was a large house and estate almost directly opposite, on the east side of London Road where Royal Parade now stands, also known as Broad Green Place. Later directories up to and including Warren’s 1865–66 also give both the London Road and Broad Green Place addresses, but those from Warren’s 1869 onwards use only the London Road addresses.

Evidence regarding John Reid and Mx de Wilde is taken from the Poor Rate books for July 1845 to October 1848 inclusive. Exact addresses are not given in the rate books, but in this case comparison between years and matching with Gray’s 1851 directory (which does give exact addresses) makes it fairly clear that John Reid was at the house later numbered as 185 London Road. I have been unable to find any more information about him.

The July 1845 book has “Aug De Wilde” listed as occupier of the house I believe corresponds to 185 London Road, but this entry is crossed out; it also has “De Wilde” as the “Landowner &c rated” for the house I believe corresponds to 187 London Road. “Aug” could stand for “August”, “Augusta”, or “Augustus”. The only person of a similar name I’ve found in the area is a 47-year-old Augusta de Wilde living in Beckenham and working as a “Military Cap Maker” at the time of the 1871 census; this may of course actually be a completely different person.

- Date of Jonathan and Ellen’s marriage is taken from an announcement on page 4 of the 15 November 1850 Evening Standard. As explained in the footnotes of my article on Broad Green House, the 1841 census lists Ellen Keen in a household at Broad Green (likely Broad Green House itself) with Jonathan’s nephew Jeremiah, suggesting a family connection of some kind. However, I’ve been unable to uncover any background information about Ellen herself, other than that the 1851 census gives her birthplace as Paddington; even her marriage announcement describes her only as “Miss Ellen Keen [...] of Croydon”.

Croydon’s Local Board of Health was created on 1 August 1849 under the provisions of the 1848 Public Health Act; more information can be found on the Museum of Croydon Collections website. Quotations regarding the memorial are taken from a report on page 3 of the 26 July 1859 Sussex Advertiser, which notes that the memorial would be presented at a future meeting of the Board. According to another report on page 3 of the 2 August 1859 Sussex Advertiser., the memorial was presented and discussed at the 26 July meeting. The first quotation from Mr Stevenson is from a report on page 6 of the 16 August 1859 Sussex Advertiser, and the second from a report on the front page of the 10 September 1859 Croydon Chronicle.

Public drinking fountains were something of a hot topic in the 1850s. According to Travis Elborough’s “A brief history of the public drinking fountain in the UK”, the first one in the UK was installed in Liverpool in 1854. This inspired the creation of the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association, which installed the first one in London in 1859. The Association was linked to the temperance movement — a linkage also reflected in Croydon, as along with the fountain at “Mr. Stevenson’s corner” the Local Board of Health were also considering “the best position for erecting a public drinking fountain to be presented by the Temperance Society” (see report on page 6 of the 23 August 1859 Sussex Advertiser).

- First quotation is taken from a report on the front page of the 10 September 1859 Croydon Chronicle, and the second and third from another report on page 3 of the 13 September 1859 Sussex Advertiser. Both of these reports give Jonathan’s initial offer as £30. Information on his later offer to increase the donation is from a report on page 3 of the 29 May 1860 Surrey Gazette, which also notes that the contractors for the work were “Messrs. King, Burton, and Hipwell, of this town” (i.e. of Croydon) and that the fountain would be made of Portland stone.

- A report on page 3 of the 19 June 1860 Surrey Gazette, covering the Board meeting of 12 June, makes it clear that the fountain had not yet been erected at that point, so it must have been put up some time between then and the Board meeting of 17 July. All quotations from Board members at the latter meeting are taken from a report on the front page of the 21 July 1860 Croydon Chronicle, which also includes a statement from another member, Mr Crafton, that “Mr. Barritt [sic], the gentleman who had kindly been at the expense of erecting the fountain at Broad Green, had not lived to see it. He died on the 3rd inst. [i.e. of this month] at Hastings. On the morning of his decease he drew a cheque for the amount.” Jonathan’s age at death is taken from an announcement on page 7 of the 6 July 1860 Evening Standard, which also confirms the date and place.

Ellen is listed (generally as Mrs J Barrett) in street directories up to and including Ward’s 1880. She also appears there in the 1861 and 1871 censuses. Her date of death and place of burial are taken from Jesse Ward’s Croydon In The Past (p154). Her death is also mentioned in a short piece on page 5 of the 4 December 1880 Croydon Guardian, which describes her as having been “one of the few remaining links connecting the present with the past generation” and “of a well-known benevolent disposition”.

It’s not clear what happened to Jonathan’s drinking fountain in the end, though it does seem to have been removed by 1896; the Ordnance Survey map published in that year (London sheet XV.94) shows the trough but not the drinking fountain. (Raymond Wheeler’s book Norbury, Thornton Heath and Broad Green has a picture of this trough on page 61.)

The Croydon Chronicle of 5 May 1888 reported that a Town Council meeting on the preceding Monday had agreed “that the disused drinking fountain at Broad Green be removed and placed in the Park Hill Recreation Ground” (page 2, “The Broad Green drinking fountain once more”), but although this fountain had been “given by a resident in the West Ward”, it seems not to have been the one funded by Jonathan. Firstly, the report states that “the gentleman who presented the fountain did so to the Drinking Fountain Association, and not to the Local Board or Town Council”, whereas according to a report on page 3 of the 29 May 1860 Surrey Gazette, Jonathan had suggested “that in order to prevent any differences in future as to the ownership of the fountain, [...] they should have the words ‘Local Board of health, 1860,’ placed upon the stone.” Secondly, the report states that the donor of the fountain “had also left two or three guineas a year for its maintenance”, but Jonathan’s will makes no mention of any such legacy.

- The 1881 census (conducted on the night of 3 April) lists the property as unoccupied, whereas Ward’s 1882 directory (based on data finalised at the end of the previous year) lists T H Barnes, M.D., M.R.C.S. The 1881 Medical Directory places Thomas Hy [Henry] Barnes at 123 St James’s Road, with the same background and qualifications as given for him on London Road in the 1882 edition, showing that this was definitely the same person; both editions list him as Medical Officer for the 4th District of the Croydon Union. The 1891 census and editions of Ward’s directory from 1885 onward confirm T H Barnes’ full name of Thomas Henry Barnes. Thomas’ wife Mary Anne also appears in the 1891 census, aged 53 (three years older than Thomas) and born in Stamford, Lincolnshire. The 1871 census, at which point Thomas and Mary Anne were living in Bedfordshire, confirms that they were married before arriving in Croydon. They were likely living in Croydon by 21 October 1874, as according to a report on page 34 of the 1875 Report and Abstract of Proceedings of the Croydon Microscopical Club, Thomas joined said club on that date. (The Croydon Microscopical Club was a precursor of the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society, of which I am a member.)

- The 1894 Medical Directory describes Thomas as “Surg. Croydon Prov. Disp.”, and an article on page 2 of the 15 October 1881 Croydon Guardian (“Croydon Provident Dispensary”) states that the staff of the dispensary at that time were “Drs. Hinton, Richardson, Dukes, and Barnes”. This is almost certainly our Dr Barnes; although his entry in the 1882 Medical Directory does not mention the Croydon Prov. Disp., no other doctor named Barnes is listed in Croydon at the time. Thomas was very likely operating a private practice from his home as well (see later description of house in 1894 sales particulars).

- Information and quotations taken from an article on page 5 of the 27 April 1882 Times (“Metropolitan Provident Medical Association”). According to this article, at that time there were eight existing dispensaries, including the one at Croydon. An article on page 2 of the 15 October 1881 Croydon Chronicle (“Inauguration of Croydon Provident Dispensary”) states that at that time the Croydon dispensary charged a joining fee of 1s for a single person and 1s 6d for a family (£5.91 and £8.86 in 2018 prices), followed by monthly payments of 6d for an individual and 1s for a family (£2.95 and £5.91 in 2018 prices). An earlier article on page 5 of the 25 June 1881 Croydon Chronicle, published a few months before the Croydon dispensary began operating, confirms that “There is no pretence of charity about it, as the terms, although low, are found sufficient to make the dispensary self-supporting.” This article also states that the premises of the dispensary at 12 Katharine Street were leased by the Metropolitan Provident Medical Association. Further information on the Metropolitan Provident Medical Association can be found on the UCL Bloomsbury Project website.

- Date of inaugural meeting and quotation describing Dr Carpenter’s speech are from “Inauguration of Croydon Provident Dispensary”, as above. The mention of “letters to the hospital” in this speech refers to letters of recommendation from those who had donated funds to the hospital; these were required before a patient could be admitted (see my article on Croydon General Hospital).

- As noted earlier, the 1894 Medical Directory describes Thomas as surgeon to the “Croydon Prov. Disp”. The 1895 edition gives a new address of 17 St Stephen’s Road, Bayswater, and describes him as “late Surg. Croydon Prov. Disp.”

The text of the 1911 National Insurance Act can be viewed online at the Socialist Health Association website, but it’s somewhat convoluted, and I am not a lawyer. My description of those covered by mandatory enrollment is taken from page 31 of the 1914 Medical Directory, in a section which discusses the Act’s implications for medical practitioners.

Information on loss of Croydon Provident Dispensary members and quotations regarding finances and closure are taken from an article on page 2 of the 2 August 1913 Shoreditch Observer. It’s not clear what proportion of the membership these 600 members represented. The Medical Officer of Health reports available on the Wellcome Library website do not give statistics on the dispensary, and although earlier editions of the Medical Directory did give numbers of patients, this practice ceased well before 1911.

A short article on page 35 of the 11 July 1914 Chemist and Druggist confirms that the dispensary was still operating as of that date, but that it had recently had to close its pharmacy “owing to the depletion of the membership through the Insurance Act taking the workers away”. It appears in the 1915 Medical Directory and Ward’s 1914 directory with an address of 53 Surrey Street, but is absent from later editions of both.

As noted in a letter to the editor of The Times signed by persons including the chair of the Metropolitan Provident Medical Association and published on 1 July 1913, the National Insurance Act certainly did not make the provident dispensaries redundant: “The Act, it must be remembered, only deals with the ‘employed person’ — i.e., the person in direct receipt of wages — and thus leaves a very large number of the industrial classes — chiefly women, and children up to 16 years of age — unprovided with medical attendance.” However, by mid-1916 the Association had disbanded; according to an article on pages 26–28 of the July 1906 Charity Organisation Review (Vol. 40 No. 235; “The Metropolitan Provident Medical Association”), by that date it was “numbered among” those “useful institutions which have been compelled to close their doors on account of [...] the enactment of new legislation”.

All information and quotations regarding the house and grounds are taken from unbound sales particulars (ref BA278) at the Museum of Croydon. The printed date on the particulars is 7 May, but this has been crossed out in pencil and substituted with 21 May. The “light Basement” was almost certainly a half-basement, partially underground but extending above ground level to allow windows high up in the walls. The ground floor of the house would have been raised some distance above the actual ground, reached via the abovementioned “Portland Stone Steps” from the front and “Stone Steps with Lattice and Creeper over” from the garden at the back.

It’s unclear why there were two kitchens. One possibility is that one of the kitchens was converted from other use in order to allow room for an extra oven and cooking range when catering for a large number of guests.

- Stephen’s place of birth is taken from the 1881 census, which shows him and Lucy living at the Rectory in Brindle, Lancashire. His date of birth, information about his academic and clerical qualifications, and time as vicar and rector are taken from his entry in J A Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses (Part 2, Vol 2, which I consulted at the British Library but which is also available on Ancestry). His place and date of death are given in Alumni Cantabrigienses as well as his entry in the National Probate Calendar. Confirmation that this is the same Stephen Ray Eddy who lived on London Road comes from his entry in the 1897 Clergy List, which gives his address as 105 London Road, Croydon (later renumbered to 185). Rev. Stephen Ray Eddy, MA, is listed at 105 London Road in Ward’s 1895, 1896, and 1897 directories, the data for which were generally finalised in early December of the preceding year. Photos of his grave can be viewed on the Find A Grave website (ref 177073236).

- The Surrey Echo caption for this misspells his surname as “Vervakye”, but another photo on page 3 of the 14 December 1908 edition showing “Mr. Percy Robinson, of High St., and Mr. Vervaeke, of London Rd.” confirms that this must be our Victor. The photo shown here was taken in George Street, according to its caption. I don’t recognise the building behind him; it may have been towards the eastern end of the street, where substantial demolition and rebuilding has taken place.

Ward’s directories list Victor Vervaeke from 1898 to 1922 inclusive. Rose and Dorothy’s names and Victor’s birthplace are taken from the 1901 and 1911 censuses (the former has “Doroth” for Dorothy, but this is obviously a mistake). Rose herself, like her daughter, was born in Croydon. These censuses give Victor’s age as 35 and 48 respectively, and his profession as “Dealer in Horses / Stable” and “Horse Merchant” respectively. Edward Gryspeerdt’s surname is a little hard to read in the 1881 census, but I’ve confirmed it via Ward’s 1880 directory. He was also a horse dealer, and may have given Victor his start in the business.

Ward’s directories list Vervaeke & Co, horse dealers, on Willett Road from 1896 to 1906 inclusive. He probably moved his stables to Lower Addiscombe Road after this; he’s listed there in Kelly’s 1915 directory, and although no street numbers are given, looking at this road on Google Street View to match the houses with the names given in Kelly’s (some of them still have the names above their doors), it seems Victor’s premises were around where the junction with Stroud Green Way is today. An article on page 7 of the 4 November 1911 Croydon Guardian mentions a person being “kicked by a cow in the stables on the premises of Mr. Victor Vervaeke, horse dealer, at Woodside”, and the area of Croydon known as Woodside could plausibly include this part of Lower Addiscombe Road. Oddly, though, Ward’s directories consistently fail to list Victor on Lower Addiscombe Road. I do also wonder what the cow was doing there.

- Date and place of Victor and Rose’s marriage is from their entry in Surrey parish registers. The 1891 census shows them living at 43 Lansdowne Road, and Ward’s directories list Victor Vervaeke there in 1890, 1891, and 1892. He is then listed at 7 Tamworth Road in 1893; 3 Drummond Road in 1894 and 1895; The Cottage on Willett Lane, near his business premises, in 1896, 1897, and 1898; and at 105 London Road (later renumbered to 185) from 1898 to 1922 inclusive. (One does wonder why he moved around so much; also, why he’s listed at two addresses in 1898.) Details of Dorothy’s marriage are also taken from Surrey parish registers. Victor’s date of death, and confirmation he was still living on London Road at the time, are from his entry in the National Probate Calendar.

- Ward’s directories list the occupants of 105 London Road (later renumbered to 185) as Victor Vervaeke up to and including 1922, Mrs Vervaeke in 1923, and Bryant Seymour Allen (actually a mis-spelling for Brian Seamer Allen — see later in article) from 1924 onwards. The 1924 edition does not include anyone of the name of Vervaeke in its alphabetical listing of residents, suggesting that either Rose moved out of the area or she moved in with another household; this could well have been Dorothy and Arnold’s household. The record of Dorothy’s marriage (see earlier footnote) gives Arnold’s address at the time as Felbrigg, Beech House Road, Croydon, and his deceased father’s name as John Smith. Ward’s directories list a Mrs J T Smith at Felbrigg from 1917 to 1922; this is almost certainly Arnold’s mother, and it’s possible that Arnold and Dorothy lived with her for a while after they married. Ward’s 1925 lists J Arnold Smith at Abbotsbury, London Road. Rose’s date and place of death, as well as the value of her effects, are taken from her entry in the National Probate Calendar.

- Brian’s birthplace and his father’s profession are taken from the 1901 census, which shows him as a 1-year-old child living at 6 Bromley Road, Lee, Lewisham. His actual year of birth is taken from his entry in the England & Wales Civil Registration Birth Index 1837–1915. The 1911 census shows him as an 11-year-old student at Lord Weymouth’s Grammar School, Warminster. The Civil Registration Marriage Index shows that a marriage between Brian S Allen and Kathleen M J Gray was registered in Lewisham district in the second quarter of 1921 (vol 1d, p 1849). I’ll discuss his time as a pilot in a future article.

- Ward’s directories list Bryant Seymour Allen [sic] in 1924–1927 inclusive and Brian Semer Allen [sic] in 1928. Electoral registers during this time spell him as Brian Seamer Allen, and this does seem to be the correct spelling, since plentiful documentation exists for this name but I can find nothing for the “Bryant Seymour” variant. (Phone books are no help, listing him simply as B S Allen.) Ward’s 1929 instead lists Robert Croucher at 185 London Road, and a B S Allen appears at 30 Oakfield Road in London phone books from September 1928 onwards. The 1929 electoral register shows both Brian (misspelled as “Bryan”) and Kathleen at 30 Oakfield Road.

- Those unable to wait for my article on the Allen-Bennett Motor Company might be interested in “Replicating ‘Old Bill’”, an article by Paul d’Orléans hosted on The Vintagent website.

- Ward’s directories list Robert Croucher in 1929, Robert Croucher and Mrs Chandler in 1930 and 1932, and “unoccupied” in 1934. The 1929 electoral register lists Robert Croucher, Edith Mary Croucher, and Mary Ann Sturt, and the 1930 register lists these three plus Mary Chandler. Edith is eligible to vote on account of her husband’s occupation of the premises, while the other three are eligible on their own account; this implies that Edith was Robert’s wife.

Albert’s baptism record shows he was baptised on 8 February 1888, son of Thomas (a carman) and Mary, in St Faith’s parish, Wandsworth. Colin Waters’ Dictionary of Old Trades, Titles and Occupations defines a carman as “Same as carter.” and a carter as “Man in charge of a cart (sometimes a stable).” The 1939 Register of England & Wales gives Albert’s birth date as 11 January 1888 and occupation as bus conductor, and Rose’s birth date as 31 December 1891 (her “occupation” is “Unpaid domestic duties”). The 1911 census confirms Wandsworth as his place of birth and gives his occupation as a general labourer working in the building trade. The record of Albert and Rose’s marriage on 30 August 1911 at St Faith’s Parish Church shows Albert as a barman and confirms his (by-then deceased) father’s profession as carman. It also shows Rose’s maiden name of Bailey and her father’s profession of engineer.

It should be noted that some sources (e.g. electoral registers and Ward’s directories) give the family’s surname as “Handscombe” rather than “Handscomb”. However, sources where the surname is handwritten by family members (e.g. the 1911 census and Albert’s signature in the parish record of his marriage) use the spelling “Handscomb”, so this is the spelling I use here.

- The 1935/1936 electoral register, which came into force on 15 October 1935, lists Albert Victor Eaton Handscombe [sic], Rose Handscombe (Senr.), Rose Handscombe (Junr.), Cyril Taylor, Ella Taylor, Thurza Bloxham, John O’Hern, and Leonard Savage. The Taylors seem to have been a separate household (they’re shown as such in the 1939 Register of England & Wales), but the other non-Handscombs may have been long-term lodgers. Ward’s directories list A V Handscombe [sic] in 1937 and 1939 (the final two editions). The 1939 Register of England & Wales, the data for which were collected on 29 September 1939, lists Albert, Rose, three records which are closed due to the individuals being born less than 100 years ago (likely the younger Handscombs), Rose F M Robson (Albert and Rose’s eldest daughter Rose Frances May under her married surname), and six other people with different surnames.

- The inhabitants of 185 London Road listed in the 1939 Register of England & Wales include Margaret Plowman, whose date of birth is given as 12 August 1920; the other lodgers were born between 1903 and 1913, making her the youngest. Her surname is crossed out to update it to Rowe and then to Wardley, suggesting she later married at least twice (this register was kept up to date with name changes for some years afterwards). Her profession is given as “Driller, Sheet Metal Aircraft Components”, and an article on page 14 of the 1 December 1939 Evening Despatch (“Girl robbed landlady spent £14 in West End”) describes her as a “pretty 19-year-old factory hand”. Details of her theft are taken from this article and from another on page 4 of the 8 December 1939 Croydon Advertiser (“Croydon Borough Bench”); the first quotation is from “Croydon Borough Bench” and the other two from “Girl robbed landlady spent £14 in West End”.

- I haven’t been able to find the Handscombs in any phone books during the 1930s–1940s — it’s likely they just didn’t have a phone — and because local and general elections were suspended during the Second World War, there are no electoral registers available between 1939 and 1946. However, they are absent from the 1946 register (which had a qualifying date of 30 June 1946). Moreover, an advert on page 11 of the 18 October 1946 Croydon Advertiser gives an address of 185–187 London Road for Marvin Hart, and the 1948 London phone book lists Marvin Hart, shopfitters, at 185 London Road. It therefore seems that the Handscombs were gone by mid-1946. Given the date of the report of Margaret Plowman’s theft (see earlier footnote), it’s likely that they remained into early 1940 at least.