The land previously occupied by 144–150 London Road is now the site of a small housing development known as Panton Close, completed in the early 2000s.

1870s–1880s: The original building, and its first occupants: Henry and Harriet Reed

Along with the rest of the eastern side of this stretch of London Road, until the mid-1860s this land was part of the Oakfield Estate, a grand house and grounds stretching over 11 hectares between London Road, St James’s Road, and the railway line up to London. The last owner of the estate, Richard Sterry, died in 1865, and the land was split up and sold off in lots to various developers.[1] The first building on this particular plot was constructed around 1877; by 1880, it was occupied by Henry and Harriet Reed, and known as The Villa.[2]

Henry and Harriet, both Brighton-born, were living on Canterbury Road in Croydon by 1861 — a side-street running off London Road a little less than a kilometre north of here. They moved to London Road in the mid-1860s, initially taking the house at number 21, further south from here towards West Croydon Station. Henry ran a bakery and confectionery from number 21, and at the time of the 1871 census he employed a total of ten assistants, five of whom lived on the premises.[3]

After Henry and Harriet moved to The Villa around the end of the 1870s, the shop at number 21 was taken over by Arthur Shears. It remained in the hands of the Shears family for the next 20 years, and remained a bakery until the early 2000s.[4]

Henry appears to have continued in the bakery business for a short while after moving to The Villa, as the 1881 census lists him as a baker employing “3 men, 1 boy, 2 females”. It’s not clear where his bakery actually was, though; street directories from 1880 onwards omit him from the list of bakers, and it seems unlikely that he would have conducted this business from his grand new house.[5] In any case, Henry and Harriet remained at the Villa only until around 1887, when they moved to Kidderminster Road.[6]

1880s–1900s: John Thrift; “Sandhurst”

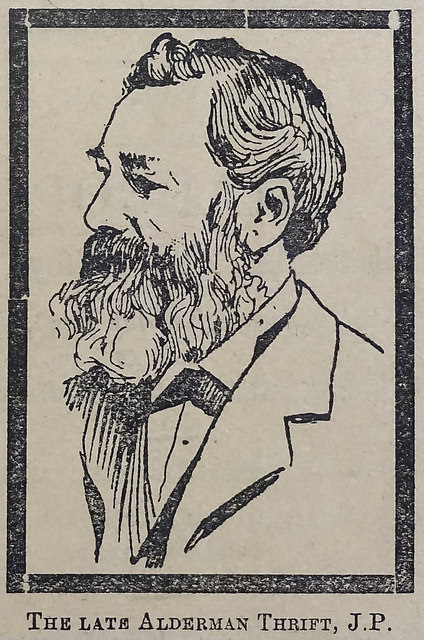

The Reeds were replaced by John and Amy Thrift, who had previously lived a few doors northwards at Arundel House, a house similarly built on Oakfield Estate land just a handful of years before The Villa. John, a wholesale grocer in his 50s, promptly renamed his new home “Sandhurst” after his birthplace of Sandhurst in Kent.[8]

Although born the son of a sawyer in a fairly rural area, John worked in the grocery trade all his adult life, mostly in Croydon. By the age of 18, he had moved to Hythe and was one of three men in the employ of a grocer named Charles Day. A year later, in early 1852, he left Kent entirely and took up a position as a grocer’s assistant in Croydon under James Graham West at 42 Church Street.[9] By 1857 he had opened his own shop at 96 Church Street.[10]

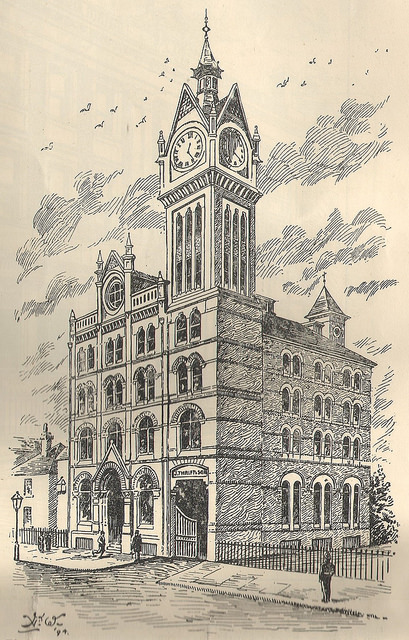

Success led to expansion, with branches opened elsewhere in Croydon as well as at Norwood, Sydenham, and Mitcham.[11] However, John was also building up a wholesale side to his business. This was originally conducted from a warehouse constructed behind 96 Church Street, but lack of space eventually led to the building of a grand new warehouse on George Street a little to the west of East Croydon Station.

The new warehouse, which opened around 1893, was used not only for storage but also for processing including bacon-smoking, tea-blending, and coffee-grinding.[12] The proximity of the station must have been useful, as the firm delivered its goods to retailers by rail as well as by horse-driven van.[13]

Around the same time as he moved the wholesale side of his business to George Street, John amalgamated the retail side with the business previously run by his son-in-law, Herbert Gosney, at 13 High Street. The High Street premises were given up, and the new partnership operated from 96 Church Street under the name of Thrift and Gosney. John’s sons Henry and William had joined him in the business, too, and the wholesale side of the business became John Thrift & Sons.[14]

John was not only a successful businessman, but also a councillor, alderman, and magistrate. His participation in Croydon public life began around the same time as his initial move to London Road, which took place around 1880. He was elected as a councillor for the town’s South Ward at the first municipal elections after Croydon became a County Borough in 1883, and appointed an alderman at the first meeting of the new Council. Around 1894 he also joined Croydon’s board of magistrates. He served for several years on the committee of Croydon General Hospital, and was involved in setting up Croydon’s Chamber of Commerce.[15]

Amy died on 5 October 1889, shortly after the move from Arundel House, but John continued to live at Sandhurst until his own death on 18 October 1903.[16] The firm of John Thrift & Sons, however, continued to trade until 1960, when it was sold to another grocery wholesaler, Edward Paul & Co of Camberwell.[17]

1900s: W G Dunn & Co

Next to arrive was William George Dunn, a baking powder manufacturer who used the property not only as his residence but also as a base for his manufacturing business.

Born in Rotherhithe in 1843, William lived in London for the first two decades of his life. By 1865 he was married to his first wife, Lydia, and working in Hackney as a perfumer; but by 1870 he had become a widower, emigrated to Hamilton in Ontario, married his second wife, Charlotte, and was working as a soapmaker. He remained in Canada until around 1887 before returning to England and setting up in business as a baking powder manufacturer on Katharine Street, Croydon.[18]

![Advertisement stating that Dunn’s Fruit Salt Baking Powder “Makes Food Delicious, Nutritious and Digestible [...] produces a moist crust and does not soon become hard and dry, and is prepared from absolutely pure healthful ingredients”. At the bottom is a drawing of the product in an oblong tin.](/history/images/0144/dunns-fruit-salt-ad-425px.jpg)

William had not been back in England long when he became embroiled in a “tedious law suit” which would take three years to resolve.[20] On 29 June 1887 he applied to register a trademark for one of his products, Dunn’s Fruit Salt Baking Powder. However, strong objection to this came from one James Crossley Eno, who ten years previously had been granted a trademark for the term “fruit salt” in two contexts: as a “proprietary medicine for human use”, and as a “dry preparation for making a non-intoxicating beverage”.[21]

James’ objection was twofold: first, that William’s proposed name was an infringement of James’ own trademark; and second, that William’s use of this term was “calculated to deceive” the public into seeing some connection between William’s baking power and James’ well-known Eno’s Fruit Salt drink. The initial judgement was in James’ favour, and although this was overturned on appeal, it was reinstated by a counter-appeal to the House of Lords on 19 June 1890.[22]

William thus failed to obtain a trademark, but this seems not to have stopped him from continuing to use the term in question — indeed, as part of the legal proceedings, James was forced to concede that “fruit salt” was an inappropriate trademark, and it was removed from the trademark register.[23] By August 1891, William was (rather cheekily, under the circumstances) advertising his own “fruit saline” drink.[24]

Along with his third wife, Elizabeth, William moved to London Road around 1904. Although he died very shortly afterwards, on 13 August 1906, Elizabeth continued to live in the house until 1911. William’s company, W G Dunn & Co, also continued to operate from the property until the same date, now in the hands of his sons Frank and Lawrence. When Elizabeth departed the premises, however, so did her late husband’s company; the latter moved to Tamworth Road and underwent a change of name to Dunn Bros.[25]

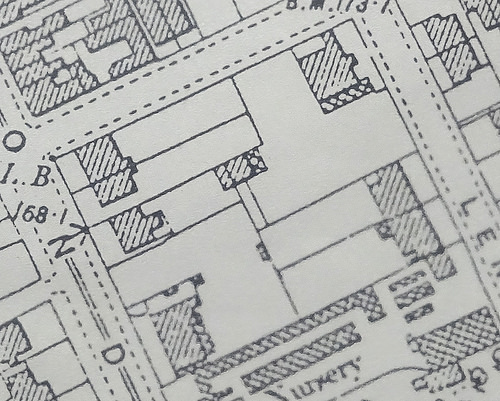

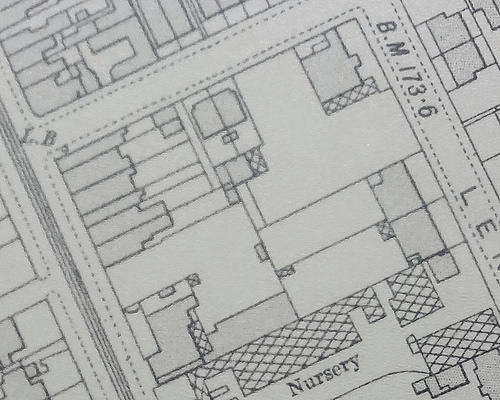

At some point during the Dunns’ residence, a small factory was constructed behind the southern end of the house for use in manufacturing their baking powder. In addition, the part of the house in front of this, which had previously been set back from the road, was extended forward to the pavement line, possibly to provide retail shop premises. It’s not clear whether this happened under William’s reign or that of Frank and Lawrence, but it seems likely that the factory was in existence by 1906, and known as the Surrey Food Works.[26]

1910s–1930s: Batchelder Bros, and Horace Marshall & Son

The departure of the Dunns signalled a separation between the original private house and the factory behind. While the former became the residence of a series of physicians (discussed below), the latter was taken over by a firm of wholesale stationers, Batchelder Bros.[27]

Bertram Batchelder, a Croydon-born 20-something who had previously worked as a stationer’s assistant, first began producing postcards around 1907. By 1908 he was trading as a wholesale stationer and relief stamper at 106 George Street, and by 1910 his brother William had joined him in the business. Around 1913, the firm known by now as Batchelder Bros moved its operations to London Road.[28]

Street directories and phone books variously describe the company as stationers “&c.”, relief stampers, printers, wholesale stationers, manufacturing wholesale stationers, merchants manufacturers, and providers of fancy goods.[29] It was a prolific publisher of postcards, many of which can still be found for sale on eBay today.[30]

Around 1933, Batchelder Bros was joined at 144 London Road by Horace Marshall & Son, a long-established firm of wholesale newsagents and publishers with a head office in the City of London and at least nine other branch offices. The two companies remained on London Road until the end of the 1930s.[31]

It’s not clear how these two companies shared the premises, but Batchelder Bros at least appears to have had a shopfront presence on London Road, situated in the part of the building that was extended forward to the pavement line during the Dunns’ time in the property.[32]

1910s–1960s: Edward Morris and Alan Pride

Around the same time as the arrival of Batchelder Bros, Dr Edward Morris moved from his previous residence at 203 St James’s Road to the house which was still known as Sandhurst. He both lived and practiced here, and remained until his retirement around 1926.[33] He was joined a year or so before he retired by Dr Percy William Lavers Andrew, who himself remained only a couple of years before moving to Bexhill.[34]

Longest to remain, however, was Dr Alan Pride, who began his general practitioner career here alongside Percy in 1926.[35] Percy may in fact have been here simply to smooth the transition from Edward to Alan; around the time of the move, the latter took over from the former as district medical officer for the Croydon Union, so it seems possible that Alan bought both practice and house from Edward.[36]

Like Edward, Alan initially used Sandhurst as both his home and his surgery, but around 1943 he moved his residence to 15 Beech Avenue in Sanderstead.[37] His tenure also saw the construction of another extension to the London Road property, this time on the north side, some time between 1932 and 1953. The size and siting of this extension suggest that it may have been built for use as a reception and waiting room for Alan’s GP practice.[38]

Geriatrics was one of Alan’s particular professional interests, and for some years he was the medical officer for Croydon Council’s retirement homes. Other GPs he worked with over the years included James Clark Cameron, Alfred Cameron Butter, Wilfred Meredith Evans and Gerald Clementson. He finally retired in 1970, after more than 40 years’ service on London Road.[39]

1950s–1980s: Perfect Scale Co, Relyance Accessories, Floral Artists, and Croydon Car Mart

While the residential side of the premises saw continuous use through to the end of the 1960s, the picture is less clear for the part that had been split off for commercial and manufacturing purposes. Batchelder Bros and Horace Marshall were likely gone by 1940, but evidence of later occupants only emerges around 1948, with the first phone book appearance of the Perfect Scale Co. This company manufactured and supplied scales for weighing both food and people (including “infant balances” for babies), as well as food slicing machines. It remained on London Road until around 1960.[40]

The mid-1950s saw the arrival of Relyance Accessories, a coilwinding firm with its head office on Bridge Street in Westminster. This was likely located around the back of the premises, and accessed via the gap in the building line to the north of the main house. According to a 1960 advert, the firm manufactured coils “for many of the largest Electrical Concerns”, including brake coils, contactor coils, and electronic coils. It remained here until around 1970.[41]

Another business known as Floral Artists was also present from around 1967 to around 1973. From the name, it seems likely to have been a florists; if so, it was probably located in the part of the premises that was extended forward to the pavement line during the occupancy of W G Dunn & Co. Conversely, Croydon Car Mart, which arrived around 1977 and remained until around 1983, was probably around the back where Relyance Accessories had been.[42]

1970s–1990s: Rosan & Co and the Croydon Auction Rooms

Alan Pride’s retirement in 1970 had left the main part of the building vacant. However, this vacancy was swiftly filled by Rosan & Co, a company of valuers, auctioneers, and estate agents founded by Leslie and Iris Rosan in the early 1960s. Originally based at 31 Lower Church Street, it moved to 256 High Street around 1969 and again to 144 London Road around 1971.[43]

Rosan & Co expanded over the years, in terms of both scope and staff numbers. By 1990 it had started doing reposessions in addition to its other business, and had 87 bailiffs on its payroll. By 1999, it was employing 138 staff and had outgrown the amount of space available at 144–150 London Road. New premises were needed, and the company found them just across the road at number 145.[44] It remained there until moving out of Croydon altogether, to Hailsham, East Sussex.[45]

2001–present: Panton Close

The departure of Rosan & Co saw the end of the 120-year-old building once known as Sandhurst, as everything on the site was demolished by late 2001 and replaced by a new residential development consisting of 13 houses and 15 flats. A small cul-de-sac known as Panton Close was constructed as part of this, leading eastwards off London Road and curving around to the fronts of the houses.[46] The story of 144–150 London Road thus came full circle — from residential, to commercial, and back again to residential — albeit now providing housing for 28 families instead of just one.

Thanks to: Alex Roberts, for additional research; James Coupe and Sean Creighton, for research advice; John Hickman and Carole Roberts, curators of the John Gent collection; Tony Skrzyptczyk; Grace’s Guide; the London Metropolitan Archives; the staff of the Maps Room at the British Library; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers bob and Kat. Census data, FreeBMD indexes, and London phone books consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Administrative note: Guess what — this is another long article! So I’m postponing the next one as usual; it will be published on 4 November 2016.

Footnotes and references

- For more on the Oakfield Estate, see my article on the old Croydon General Hospital site. Area of Oakfield Estate at the time of its breaking-up assessed via an area calculation on Google Maps using the 1867 map reproduced in that article as a guide.

- This building is omitted from Ward’s 1876 directory, but appears in the 1878 edition as an unoccupied “New House”. The 1880 edition lists Henry Reed, “The Villa”. Henry’s wife’s name is taken from the 1861, 1871, and 1881 census; the first two of these have her as “Harriet” and the last has “Harriett”. In addition, the house appears on the 1896 Town Plans but not the 1868 edition.

- Henry and Harriet’s place of birth, residence as of 1861 and 1871, and employees in 1871 all taken from census data. Regarding the date of their move to 21 London Road, they first appear here in the June 1864 Poor Rate Book and in street directories from Simpson’s 1864 onwards.

- Henry Reed, baker and confectioner, appears at 21 London Road (11 in contemporary numbering) in street directories up to and including Ward’s 1878, and thereafter at The Villa. See my article on 21 London Road for more on Arthur Shears and the rest of the history of that address.

- It also seems unlikely that this listed profession relates to his having retained control over the business at number 21; the same census lists Arthur Shears as the employer of five men and two boys, which doesn’t match up with Henry’s list of employees.

- Ward’s directories list Henry Reed at 38 Kidderminster Road from 1888 onwards, and the 1891 census confirms that this was the same Henry Reed.

- Image provided by Tony Skrzyptczyk, scanned from his own copy of “Old & New Croydon Illustrated”. Description of building taken from “Croydon architect’s delightful piece of Victoriana”, A L Terego, Croydon Advertiser, 11 September 1959; this also includes a drawing of the clock as seen from Wellesley Grove behind Norfolk House, described by the author as an “unexpected” view and “[o]ne of the most piquant” of the many views of the clock from different parts of the town. A photo of the warehouse frontage from George Street (looking from the west, as opposed to the drawing from the east reproduced here) can be seen as a clipping in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon; this has no provenance information attached to it, but comparison with microfilm shows that it was taken from the front page of the 26 August 1960 Croydon Times.

- Ward’s directories list John Thrift at Arundel House from 1880 to 1887 inclusive, and at Sandhurst from 1888 onwards. The placing of Sandhurst in these directories makes it clear that it was the house previously known as The Villa. Amy’s name and John’s age, birthplace, and profession are taken from the 1891 census.

- John’s father’s profession is taken from the 1841 census, which lists the family’s neighbours as being primarily agricultural labourers, plus a few farmers and other trades such as miller and grocer. Information on John’s working at Hythe is taken from the 1851 census. The date (“the early part of 1852”) of his move to Croydon, his employer’s name, and the name of the street where he first worked in Croydon are taken from his Croydon Chronicle obituary. The street number of James Graham West’s shop is taken from Gray’s 1853 directory, which also lists him as having premises at 1 Market Street.

- John’s 1903 Croydon Chronicle obituary states that at that point it had been “a little over 46 years since he opened a small shop in Church-street”. In line with this, a 1957 Croydon Times article quotes the then-chair of directors of John Thrift and Sons Ltd as saying “We have books dated 1857 which shows [sic] that the business had already been in existence some time then, but how long before 1857 John Thrift and Sons Ltd., came into being, I don’t know... and nor does anyone else.” (“A century of service”, Croydon Times, 22 November 1957). It seems unlikely that the business was in existence much before 1857, as John Thrift, Grocer and Cheesemonger, is listed at 91 Church Street in Gray’s 1859 directory, but completely absent from the 1855 edition.

- History of John Thrift & Sons, Ltd, compiled May 1946 at 69 George Street and printed by W D Hayward, 11–12 Park Street; shelfmark pS70 (641.4) THR at the Museum of Croydon. Much of this small booklet is reproduced verbatim (although without attribution) in “A century of service”, Croydon Times, 22 November 1957.

John’s 1903 Croydon Chronicle obituary says the warehouse in George Street was opened around 1893, and entries in Ward’s directories confirm this. Information about food processing at the warehouse is taken from History of John Thrift & Sons, Ltd, which states that “Stoves for smoking bacon were built at the back of the premises in George Street, and machinery was installed for milling, blending and packing tea, fruit cleaning and coffee grinding.” Further description of the warehouse can be found in “Croydon architect’s delightful piece of Victoriana”, A L Terego, Croydon Advertiser, 11 September 1959.

Several sources (e.g. “Death of Alderman Thrift”, Croydon Chronicle, 24 November 1903; “Stray Shots”, Croydon Times, 29 August 1960, page 8) state that the clock in the warehouse tower was taken from the old Croydon Town Hall, which was in the High Street until it was demolished in 1893 and superseded by the present Town Hall in Katharine Street. One of these gives the additional detail that “John Thrift bought the clock from the old Town Hall for fifty guineas [£6085 in 2015 prices] from the Corporation in September, 1893, and had it incorporated in his new warehouse” (History of John Thrift & Sons, Ltd). However, I have been unable to find contemporary confirmation of any of this (aside from the location and demolition date of the old Town Hall, both of which are well-documented). The Croydon Advertiser and Croydon Guardian editions published in September 1893 contain much discussion of the Town Hall demolition, with the general gist that there was little of value in the reclaimable materials. One article states that the entirety of the building was sold to a contractor for £55 (£6375 in 2015 prices), which makes a price of 50 guineas just for the clock seem unlikely. A brief article in the 16 September Croydon Advertiser states that “The last piece of the old clock-tower was pulled down with a crash soon after two on Thursday afternoon”, but no mention is made of the clock (“The Argus Letters”, Croydon Advertiser, 16 September 1893, page 5). Moreover, an article published a week later praises the “new clock at Messrs. Thrift and Son’s premises”, which seems implausible wording to describe a clock rescued from the old Town Hall (“The Argus Letters”, Croydon Advertiser, 23 September 1893, page 5), and another article in the same issue describes an auction of the “first portion of the materials of the old Town Hall [...] chiefly consisting of timber, beams, partitions, and window sashes, York paving stone, floor-boards, and girders”, again with no mention of the clock (“Sale of the old Town Hall materials”, Croydon Advertiser, 23 September 1893, page 8).

- The John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera at the University of Oxford includes a John Thrift & Sons flyer (ID: 20081006/15:56:40$kg) dated 19 December 1896 giving wholesale prices for various fruit and vegetables and offering delivery “Free on Rail Croydon Station, or [...] by own Vans within our usual Town radius.” The previously-cited 1957 Croydon Times article states that “Goods were delivered as a rule by horses and vans, but some goods were sent by rail or carriage. For a heavy load, a van with a team of three horses would be used. Some journeys took two days and the carman would put up for the night at a village at the furthest point on his journey.”

The names of John’s sons, and the names of the retail and wholesale sides of the business, are taken from History of John Thrift & Sons, Ltd. This source states that the amalgamation took place in 1888; however, Ward’s directories list Herbert Gosney & Co at 13 High Street and J Thrift & Sons at 96 Church Street, up to and including 1892, with Thrift and Gosney first appearing at 96 Church Street in 1893. (The 1893 directory lists Gould, Wreford & Co, outfitters, at 13 High Street, suggesting that Gosney gave up his premises there.) Henry and William (aged 11 and 5 respectively) are listed in John’s household in the 1871 census, along with their 9-year-old sister Amy; no other siblings are listed, so presumably it was Amy who married Herbert Gosney and brought him into the family.

Henry’s American-born wife Mattie (née Lawrence) was perhaps the most famous of the family. Before her marriage, she was a member of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a Black singing group which took its repertoire of Negro spirituals to Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and Australia. She and Henry married in Croydon on 21 October 1890. (The preceding information is all taken from an article by Jeffrey Green). I’ve found no evidence of her ever living on London Road, but the 1891 census has her and Henry at 71 Oakfield Road, just off London Road. (Henry is recorded around the same time as having participated in the ceremony of “beating the bounds” of Croydon parish in 1894; see John Hickman, “Beating the Bounds in Croydon in 1894”, CNHSS Bulletin 157 [Sep 2016], pp. 13–19.)

- As noted in the previous footnote, Ward’s directories list John Thrift at Arundel House, London Road, from 1880. Information on his service as councillor and alderman as well as that regarding the General Hospital and Chamber of Commerce is taken from his obituary in the 14 November 1903 Croydon Chronicle. This also notes that he had “on more than one occasion been asked to fill the position of Mayor and Chief Magistrate of Croydon,” but declined “after consulting his medical advisor”. Information on magistracy is taken from the lists of Borough Justices in the prefaces of Ward’s directories; John first appears here in the 1895 edition.

- Amy’s date and place of death are taken from the GOV.UK “Find a Will” search. According to an article in the 12 October 1889 Surrey Mirror (“The Murder of a Croydon Woman”, page 3, column 4, viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription), Amy’s death was “somewhat sudden” (though note that Amy is not the “Croydon Woman” referred to — her mention in the piece is because her funeral took place on the same day). John’s date and place of death also taken from the GOV.UK “Find a Will” search.

- “Century-old firm of wholesale grocers is sold”, Croydon Advertiser, 26 August 1960, front page. This also states that, according to one of the company’s directors, the sale was due to the gradual dying-out of small- and medium-sized grocery shops, which had been the firm’s main customers: “Their places were being taken by big shops and self-service stores, who [sic] had their own wholesale depots.” According to a front-page article in the Croydon Times of the same date, a preliminary planning application had been made to demolish the warehouse and build a block of offices and shops in its place, but this was turned down by Croydon Council as “The site has a very narrow frontage and is not considered suitable for development of this type.”

William’s birthplace, birthdate (first quarter of 1843), residence in 1870, and profession (in 1871) provided by family historian Alex Roberts using English and Canadian census data and Ontario marriage registers. William’s residence, spouse, and profession as of 1865 are taken from the record of marriage between William George Dunn and Lydia Esther Miller on 24 February 1865 at St Philips, Dalston (this matches well with his father’s name, also provided by Alex Roberts from the Ontario marriage register, and his entry in the 1861 census, in Hackney with his parents Arthur and Louisa). It seems likely that Lydia died in early 1869; her marriage record states that she is “under age” (i.e. under 21), which along with her name and residence matches well with the 23-year-old Lydia Esther Dunn who the FreeBMD Death Index lists as having died in Hackney in the first quarter of 1869.

William appears in the 1881 Canadian census, and the 1901 England census (which was taken on the night of 31 March/1 April) lists him as having a 13-year-old son born in Canada. This suggests that he was likely still in Canada at the start of April 1887, though it is of course possible that he returned to England earlier than that, while his wife remained in Canada until after giving birth. (The 1901 census wrongly lists him as William J Dunn, but Ward’s directories entries from around this make it clear that the “J” is a typo and this was definitely our William.)

Ward’s directories list William G Dunn (or W G Dunn) at Montreux, 43 Birdhurst Rise, from 1889 to 1897 inclusive; William George Dunn at a house called “Hamilton” on Friends’ Road (the part now known as Edridge Road, roughly where Edridge Road Community Health Centre is today) from 1898 to 1904 inclusive; and W G Dunn & Co, baking powder manufacturers, at 18a Katharine Street from 1889 to 1904 inclusive. William is absent from the alphabetical lists of traders and residents in the 1888 edition. He likely named the Friends’ Road house himself, given his Canadian residence in the town of the same name.

- This is a photograph of a photocopy of the directory. The photocopy, which cuts off the words “ONCE USED, ALWAYS USED.” from the bottom of the advert, can be found in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon. Although the Museum also holds an original copy of this directory, it has been rebound so tightly that getting a decent photo of the advert is impossible.

- Quotation taken from “Eno v. Dunn”, page 8, column 5, Croydon Advertiser, 21 June 1890. This report includes the slight exaggeration that the legal wrangles took “some four years”, rather than the actual three.

- Information and quotations taken from James Crossley Eno v William George Dunn, House of Lords, 19 June 1890, (1890) 15 App. Cas. 252 (pp 253, 259).

- James Crossley Eno v William George Dunn, House of Lords, 19 June 1890, (1890) 15 App. Cas. 252. Some details of the case are also reported on pages 387–389 of the 22 March 1890 Chemist and Druggist, available online from the Internet Archive.

- It isn’t entirely clear to me why James’ registration of “fruit salt” as a trademark was considered inappropriate. The record of William’s appeal against the initial judgement in James’ favour (In Re Dunn’s Trade Marks, Court of Appeal, Chancery Division, 9 April 1889, (1889) 41 Ch. D. 439) notes that James had registered the term “fruit salt” as “an old trade-mark” but that in the initial hearing his lawyers “stated that they were unable to prove that ‘Fruit Salt’ had been used as a trade-mark before August, 1875, and therefore they felt it necessary to abandon the registration of those words.” One of the presiding justices, Lord Justice Fry, also stated that “In the first place, the words are both common English words, and, in the next place, they are so collocated as to become descriptive words. I do not mean that they communicate any exact information, or give any definite notion, but they do convey an intelligible, if a vague notion.” It thus seems possible that “fruit salt” was considered to be a common descriptive term which could not be trademarked, but I’m not sure of the relevance of proving trademark use before August 1875.

- See the 22 August 1891 Croydon Advertiser advertisement reproduced here. James had the last laugh, however; while William’s name has descended into obscurity, Eno’s fruit salt is still on sale today, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline as an antacid product under the name “Eno”.

Ward’s directories list W G Dunn & Co, baking powder manufacturers, at number 50 (later renumbered to 144) from 1905 to 1911 inclusive, William George Dunn “(resident)” at number 50 in 1905 and 1906, Mrs Dunn “(res.)” at number 50 in 1907, Mrs W G Dunn at number 52 from 1908 to 1911, and Dunn Bros, custard powder manufacturers, on Tamworth Road from 1912 onwards. The business of baking powder manufacture thus clearly took place somewhere on the London Road premises. Mrs Dunn’s first name is taken from the 1911 census, which shows her as a widow, head of the household, living at 52 London Road with four sons aged from 8 to 25; the oldest two sons, Frank and Lawrence, are listed as a travelling salesman and manufacturer, respectively, of baking powder and custard powder, and the next-oldest, 19-year-old Christian, as “Assisting in Business”. William’s date of death is taken from the National Probate Calendar.

It isn’t entirely clear whether Frank and Lawrence were Elizabeth’s sons or her stepsons. They were 23 and 25 years younger than her, making them plausibly her sons, but I haven’t managed to find out when and where William and Elizabeth married, so they could actually have been Charlotte’s.

The 1913 Ordnance Survey map shows a building behind and adjoining the house which was not present on the 1894–1896 edition (excerpts of both maps are reproduced here). John Thrift lived in the house from the late 1880s to 1903, and as a grocery wholesaler with premises elsewhere seems unlikely to have constructed an extension that the Dunns could have made use of to manufacture their baking powder. As W G Dunn & Co had actually left by 1913, there is a small possibility that the factory and extension were built by its successor, Batchelder Bros, but Ward’s directories show W G Dunn & Co’s business premises at 18a Katharine Street, then on London Road, and then on Tamworth Road, with no overlap. Moreover, an advert on page 7 of the 15 August 1906 Croydon Times makes clear reference to W G Dunn & Co’s “Surrey Food Wks”, which would seem an odd way to refer to a manufactory situated in a private house. (Unfortunately there are no large-scale Ordnance Survey maps available for the area between 1896 and 1913.)

The change in numbering in Ward’s directories (see previous footnote) could suggest that the baking powder was initially manufactured in part of the house before the factory was constructed, or it could simply mean that it was not initially realised that a separate address for the factory would be a good idea, or perhaps after William’s death his widow wanted to make a clearer distinction between the factory and her home.

There is a possibility that the factory might also have been known as the Dunn Food Works; Nancy Seger states in a message on the RootsWeb KENT-ENG mailing list dated 9 September 2008 that a correspondent of hers has letters to an ancestor from William, written on Dunn Food Works headed notepaper. I haven’t been able to corroborate this, though; searches in the British Newspaper Archive and the Times digital archive for “Dunn Food Works” and “Dunn’s Food Works” revealed nothing.

- Ward’s directories list Batchelder Bros (initially under the mis-spelled name “Batcheldar Bros”) at number 50 from 1914 to 1927 inclusive and thereafter under the renumbered address of 144; and various surgeons/physicians at number 52 and its renumbering of 146 during the same years. The split of numbering (50/144 vs. 52/146) makes sense here, as London Road is numbered from south to north and various Ordnance Survey maps make it clear that the entrance to the factory was south of the entrance to the house.

- In his book A View of Croydon, local historian John Gent states that “Bertram Batchelder first produced a few printed postcards around 1907” (page 6). Ward’s directories list B Batchelder, “W’sale. Stnr., Rlf. Stamper” at 106 George Street in 1908 and 1909; Batchelder Bros, wholesale stationers, at the same address from 1910 to 1913 inclusive; and Batchelder Bros under various designations at 144 London Road (50 before 1928) from 1914 onwards. The 1901 census lists Bertram and William living with other siblings and their mother Annie at 28 Windmill Road; Bertram is an 18-year-old stationer’s assistant born in Croydon and William is a 25-year-old grocer’s assistant born in Smithfield, London. The 1911 census shows the brothers living with both parents at 99 Addiscombe Road; both are listed as wholesale stationers (though Bertram is an “Employer” while William is a “Worker”), and two other siblings at the same address, 33-year-old Maude and 30-year-old Ernest, are listed as wholesale stationers assistants.

- Descriptions of the company are taken from Ward’s and Kelly’s street directories between 1908 and 1939, and the February 1939 London phone book.

- John Gent states in A View of Croydon (page 6) that Batchelder Bros may have worked in collaboration with photographic studio Bender & Lewis and printing firm The Photo Printing and Publishing Company further up London Road at numbers 454 and 456 respectively.

Horace Marshall & Son, “Whlsl Nwsagts, Pubrs”, is listed at 89a George Street in London phone books up to and including May 1933, and at 144 London Road from November 1933 to November 1939 inclusive. Throughout this time, its main address is listed as Temple House, Temple Avenue, EC4. At its first appearance on London Road, other branches are listed at 126 Camberwell Road SE5, 44 Ilford High Road, 24 Islington Green N1, 132 New Cross Road SE14, 27 Praed Street W2, 2a Fords Park Road E16, 44a The Mall W5, Palmer Place N7, and 16 Victoria Crescent SW19; the first five of these (along with the EC4 office) persist in London phone books after the disappearance of the Croydon branch. The company also appears at 144 London Road in Ward’s 1937 and 1939 directories as H Marshall, wholesale newsagent (the edition previous to 1937 appeared in 1934, with data gathered in late 1933 — presumably too early to pick up its move from George Street). Regarding the date it left London Road, this seems to have been in May 1940, as the masthead of the company’s Weekly Trade Notes (British Library shelfmark LOU.LON 354 [1940]) lists a Croydon branch up to and including 18 May 1940, but this is absent from 25 May onwards. The Ealing branch seems to have closed around the same time.

According to an obituary of Horace Brooks Marshall (the “Son”) on page 14 of The Times, 30 March 1936, Horace Marshall & Son grew from “small beginnings” to become one of the largest wholesale newspaper agents/distributors in the United Kingdom. Before his death, Horace became an Alderman of the City of London, Lord Mayor of London, and Baron of Chipstead. Further information can be found in his Wikipedia entry and in the pamphlet Horace Marshall: Methodist, Mason and Mayor by Janet Weeks (available at the British Library under shelfmark YKL.2016.a.8019). It seems unlikely that he ever had much to do with the day-to-day running of the Croydon branch.

Batchelder Bros is listed at 144 London Road in Ward’s directories up to the final edition in 1939. It also appears in the February 1939 London phone book, but is absent from the February 1940 and following editions (the August 1939 edition on Ancestry.co.uk is missing the section of pages that Batchelder Bros would have been in).

- Batchelder Bros’ shopfront can be seen in a photograph which forms part of the London Road section of the John Gent collection, owned by the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society (CNHSS). (I’m not able to provide a more detailed reference for this image as the collection is still being catalogued.)

- Edward Morris, MRCS Eng & LSA 1886 (St Bart) is listed in the Medical Directory at 203 St James’s Road, Croydon up to and including the 1913 edition, at “Sandhurst”, 52 London Road, Croydon from 1914 to 1926 inclusive, and as “retired” to “Glyn Garth”, Linden Avenue, Bognor in 1927. He also appears on London Road in Ward’s directories (as E Morris) from 1914 to 1924 inclusive.

- Percy Wm. [William] Lavers Andrew, MRCS Eng & LRCP Lond 1915 (Middlx) is listed in the Medical Directory at “Glenelg”, Poulton-le-Fylde, Lancashire, up to and including 1924, at 5 Montpelier Crescent, Brighton, “(temporary)” in 1925, at 52 London Road, Croydon, in 1926 and 1927, and at 9 Upper Station Road, Bexhill, Sussex in 1928. He also appears on London Road in Ward’s 1925 and 1926 directories, as well as Kelly’s 1927. Note his date of qualification: 1915. According to his obituary in the 26 May 1979 British Medical Journal, he served in the First World War first as a dresser and then (after qualifying) as a battalion medical officer; this also states that Bexhill was where he spent “[m]uch of his professional life”.

- Alan Pride, MD St And 1924, MB, ChB 1922 (Dundee) is listed in the Medical Directory at 4 Oakwood Terrace, West Park Road, Dundee, in 1926, and at “Sandhurst”, 52 London Road, Croydon, from 1927 onwards. He also appears in Ward’s directories from 1927 until the final edition in 1939. His obituary in the 4 October 1980 British Medical Journal states that he “enter[ed] general practice at Croydon in 1926”.

- Edward’s Medical Directory entries describe him as “Med. Off. No. 4A Dist. Croydon Union” while Alan’s use the phrase “Dist. Med. Off. Croydon Union” without specifying the district. The Croydon Union (or Croydon Poor Law Union) was a body formed in 1836 following the 1834 Poor Law, an Act of Parliament that reformed the way poverty relief was dealt with. One of the purposes of the Union was to provide health care to those unable to pay for it themselves.

- London phone books list Alan on London Road alone until 1942, but from 1943 they also give a separate address of 15 Beech Avenue, Sanderstead.

- The extension is absent from the 1932 Ordnance Survey map but present on the 1953 edition. Measuring on the 1953 1:1250 edition (sheet TQ3166SE, performed digitally using images from the National Library of Scotland) puts its footprint at around 43 square metres.

- Alan’s

obituary in the 4 October 1980 British Medical

Journal states that he “developed a particular interest in

the care of the elderly — long before this became a recognised

specialty — and for many years [...] was responsible for the medical

care at the borough’s homes for the elderly. This is borne out by his

entries in the Medical Directory; for example, the 1960

edition lists him as “Med. Off. Croydon Corp. Hostels for Old People”.

The obituary also states that he retired in 1970. According

to his

entry in the National Probate Calendar, as well as an announcement

on page 16 of the 21 March 1980 Croydon Advertiser, he

died on 17 March 1980 at Sandwich in Kent.

The names of Alan’s partners are taken from Ward’s directories, London phone books, and the Medical Directory. Not all were based on London Road — James and Alfred were in Wallington, and Gerald was on Lloyd Park Avenue — but all are listed in the Medical Directory as being in practice with Alan under the names “Pride and Cameron”, “Pride, Cameron and Butter”, and “Pride and Clementson”. The abovementioned Croydon Advertiser death announcement also mentions the Wallington practice.

Batchelder Bros and Horace Marshall appear in phone books up to and including the 1939 London edition, and are absent thereafter. The Perfect Scale Co appears (as the “Prefect” [sic] Scale Co) in phone books from the 1948 London edition to the March 1960 Croydon edition inclusive. The advertisement reproduced here suggests that the name in the phone books is a spelling error, though a curiously persistent one, particularly as the company appears to have paid extra for its entry to appear in bold text. Details of products are taken from the abovementioned advert as well as phone books and Kent’s street directories.

Ordnance Survey maps show that the factory was known as Progress Works by 1953, but I’ve not been able to find out who gave it this name (or why).

- Relyance Accessories, Coilwinders, is listed in Croydon phone books from 1957 to 1970 inclusive. Surrey phone books give the additional address of Lahore Road, Croydon. Details of items manufactured, along with address of head office, are taken from the 1960 Ryland’s Directory advert reproduced here. Palace Chambers has since been demolished, but according to 1951 Ordnance Survey map sheet TQ3079NW, it was on the north side of Bridge Street, which runs between the northeast corner of Parliament Street and Westminster Bridge. My assertion about access to the premises comes from examination of the 1968 photograph reproduced here, as well as the previously-cited photograph from the John Gent collection. The latter shows a “goods entrance” at the very south of the property, just to the right of the extended shopfront, but this looks too narrow to be a plausible access for an industrial manufacturer.

- Floral Artists is listed in Croydon phone books from August 1967 to March 1973 inclusive. Croydon Car Mart is listed from July 1977 to May 1983 (Caterham edition) inclusive. Brian Gittings’ 1980 survey of central Croydon retail also lists Croydon Car Mart, with the annotation “(J Morris)”. Regarding the position of Floral Artists within the premises, recall that the main part of the house was still a GP surgery until 1970.

- Names of founders of Rosan & Co, date of founding, and the fact that the company did valuing and auctioning, all taken from the history page on the Rosan Reeves website. This page states that the move from the High Street took place in the early 1980s, but the documentary evidence suggests it was actually the early 1970s. Phone books list Rosan & Co, Est Agts [estate agents] at 31 Lower Church Street from February 1963 to April 1968 inclusive; at 256 Croydon High Street from September 1969 to July 1971 inclusive, and at 144 or 146 London Road from February 1972 onwards. (The company is entirely absent from the December 1961 and April 1962 editions.) Moreover, the firms files at the Museum of Croydon include two advertisements for Rosan & Co at 144–150, annotated as coming from 1973 and 1977 respectively.

- Information about the situation as of 1990 is taken from “Bailiffs boosted to meet big rise in repossession”, Croydon Advertiser, 6 July 1990, page 10. Information from 1999 is taken from “Planning department’s red tape blamed for threatened job losses”, Croydon Advertiser, 24 September 1999, page 7. Regarding the move to number 145, the history page on the Rosan Reeves website states that “the business crossed to the opposite side of the road” in 1999. Rosan & Co is listed at 145 London Road in phone books from January 2001 onwards (this being the first post-1999 phone book available), and Google Street View imagery from 2008 shows signage at number 145 for Croydon Auction Rooms and the Rosan Group of Companies.

- Information on move to East Sussex is taken from the history page on the Rosan Reeves website; this unfortunately doesn’t give a date. Phone books confusingly continue to list Croydon Auction Rooms at 144 London Road up to 2007–2008, well after the old buildings were demolished, so it’s unclear how much credence can be put in the fact that they list Rosan & Co and Rosan Heims PLC at number 145 up to the same date.

According to MasterMap digital data from Ordnance Survey (viewed in the British Library maps room), the buildings of Panton Close were in existence by 6 November 2001. Moreover, the draft version of Croydon Council’s 2002 planning and design brief for the old General Hospital site states that “A new residential development at 144–150 London Road comprising 13, 3 and 4 bed houses and 15, 2 bed flats has recently been completed” (paragraph 2.20). This draft version is available in paper form at the Museum of Croydon in green box s70 [362] CRO [General Hospital]). For some reason, the relevant paragraph does not appear in the final version of the brief (available in PDF form at the Internet Archive).

Panton Close itself was probably named after Elizabeth Panton, who as explained in my article on the old General Hospital site was the occupier of the Oakfield Estate at the time when the 1800 Inclosure Map was drawn up.