For the past two decades, the corner property at 212 London Road has been occupied by Sri Lankan restaurant Spice Land.

1900s: Davies Bros

Along with the other properties in Royal Parade (known today as 206–272 London Road), number 212 was built at the start of the 20th century on part of what used to be the grounds of the Broad Green Place estate. The first occupant was Davies Bros, a fancy drapery and millinery that arrived in late 1902 shortly after construction of the parade was completed. An advertorial in the Croydon Chronicle described the delights on offer:[1]

A pretty Christmas display can be seen at Messrs. Davies Bros., who have just opened a large establishment at the Royal Parade, where they have a choice selection of fancy drapery, millinery, ladies underclothing, baby linen, lace collarettes, handkerchiefs, blouses, furs, dolls, aprons, as well as a number of articles suitable for Christmas and New Year presents.

Despite promising “immense bargains [...] in all departments” as well as the enticement of “dressmaking on the premises”, Davies Bros lasted less than a year at number 212. By early December 1903, the premises were vacant.[2]

1900s–1910s: City Boot Company

The next documented occupant was the City Boot Company, in place by the start of 1907. This had a much longer tenure than Davies Bros, remaining here for around a decade.[3]

The company does seem to have changed hands at least once during its time on London Road. An August 1907 newspaper report of “a great disturbance in the shop” caused by a customer who arrived “the worse for drink” names the proprietor as Thomas Allen, while the relevant entry in Kelly’s 1910 directory gives the names of Farren and Baker.[4] In any case, it was gone by the end of 1917, and the premises once more fell vacant.

1920s: Walter Noel Weedon, artists’ colourman

By the start of the 1920s, number 212 was home to an artists’ pigments shop run by 20-something Walter Noel Weedon. Walter seems to have begun his career as a shipping clerk, before pivoting to artists’ materials — possibly inspired by his father, who was a commercial artist. Around 1927 he moved his shop a few doors down to number 208, and so his full story is given in my article on that address.

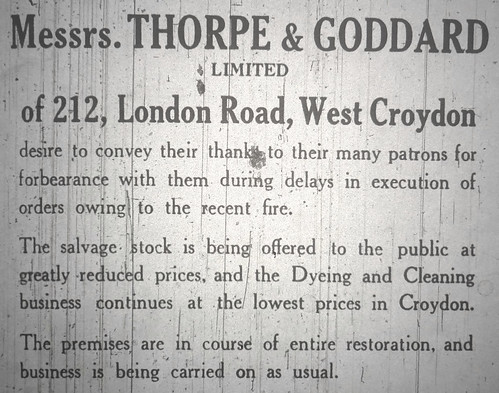

1920s–1930s: Thorpe & Goddard, general outfitters

Walter’s replacement was Thorpe & Goddard, a clothing shop run by three partners: Alfred Richard Thorpe, Francis Goddard, and Mr Planner. Some or possibly even all of the clothes seem to have been made on the premises, with an office and workshops at the rear of the shop; and the company also offered dyeing and cleaning services.[5]

Three years after arriving on London Road, the firm suffered a substantial setback due to a fire that broke out in the early hours of Thursday 30 October 1930. Believed to have started in the office behind the shop, the fire caused damage “assessed at about £600” [£39,513 in 2019 prices]. The Croydon Advertiser reported:[6]

“A large quantity of the stock was completely destroyed, several large mirrors were shattered and the structural part of the building was badly damaged. The plate glass window in the front of the shop remained intact, though every one of the many windows at the side and rear of the house were shattered by the heat. A large door leading from the rear of the shop to the yard was destroyed and the ceilings of the shop, office and workrooms were much damaged.”

The shop itself seems to have got off relatively lightly, to the point where “the firm were able to carry on business as usual the same morning” — albeit with a warning to customers that “Messrs. Thorpe and Goddard [...] must ask forbearance if they are not able to deliver all goods ordered this week.”[7]

The next setback was even more serious. Although on paper there were three directors of the company, almost all of its affairs were entirely in the hands of Alfred Thorpe. As Francis Goddard explained later, “He would not tell you anything [about the affairs of the company]. All we got to know was at the Board meetings.” Moreover, Francis “had often signed blank cheques for Mr. Thorpe. He had explicit faith in him and thought it was for the business.”[8]

This faith was entirely misplaced. In early 1936, Francis learned that a large number of fraudulent Thorpe & Goddard share certificates were in existence, produced by Alfred with forged signatures of the other two directors. Unable to locate Alfred to ask what was going on, Francis placed the matter in the hands of the police, whose investigation later showed that transactions in these forged shares “had apparently been going on for some years” and that the amount of money involved came to “a great many thousands of pounds”.[9]

The reason Francis was unable to find his partner appears to have been that Alfred was on holiday in Bournemouth with his wife Annie at the time. Returning on 20 April, the couple took a taxi from Waterloo to Thornton Heath Pond, where Alfred was dropped off “to go to the shop for a few minutes” while Annie continued home in the taxi. The next time Annie saw her husband was on the evening of 4 May, when Alfred arrived home in the same taxi, unconscious and breathing heavily. A doctor was called, but “found Mr. Thorpe dying, and he passed away a few moments later”.[10]

Although Alfred was known to be in poor health, the cause of his death was not illness but “a narcotic poison, probably chlorodyne”. At the inquest, Alfred’s regular doctor assured Croydon Coroner’s Court that his “usual heart medicines [...] contained no narcotic of any kind”. The pathologist who performed Alfred’s postmortem explained:[11]

“[...] chlorodyne was easily obtained anywhere. It contained ether, chloroform, morphia, and prussic acid [...] People took it because it dulled their senses and made them forget their worries. After one or two doses they were not in a condition to note how much they were taking and might take an overdose accidentally.”

It does seem possible that narcotic drugs were not only the cause of Alfred’s death but also the sink down which his stolen money was poured. His home at 10 Beechwood Avenue was a modest two-storey terrace, and when asked at the inquest whether she and her husband were “comfortably off”, Annie stated that they “led a very simple life”. Alfred certainly seems to have been able to spend money pretty rapidly; during the last two weeks of his life, he parted with all but two shillings of the £100 (£7,120 in 2019 prices) he had brought home with him from Bournemouth, as well as his coat and his watch-and-chain, and had borrowed £6 from his taxi-driver.[12]

Thorpe & Goddard never recovered from this. On 18 May 1938, Mr Justice Singleton in the King’s Bench Division ordered the company to pay out £5,027 (£341,000 in 2019 prices) plus costs to nine of the people who had bought fraudulent shares. Two months later, Thorpe & Goddard was in liquidation.[13]

1940s–1970s: Molbee Motors

It’s unclear what happened to the premises immediately after the demise of Thorpe & Goddard; Ward’s street directories ceased publication in 1939, and Croydon Council’s planning records are silent on the matter of 212 London Road during the 1940s. By late 1949, however, this former clothes shop had been converted to a completely different type of retail with the arrival of Molbee Motors, a Ford dealer specialising in low-mileage used cars.[14]

Molbee Motors also had works premises on Oakwood Place, a back alley just off London Road near Mayday Hospital (now Croydon University Hospital). According to its entries in the phone book, the firm used 212 London Road as a showroom; presumably, before it took over the premises, customers were simply expected to view the cars at Oakwood Place. The new showroom, with its prominent corner location on the main road running out of Croydon towards central London, must have made quite a difference to the firm’s visibility — and hence to its sales.

David Godfrey, whose father Alan ran the Sport Craft shop at 224 London Road during the same period that Molbee Motors was at number 212, remembered the showroom and its owner, Mr Molbee:[15]

[...] there were cars (2 or 3 maybe) inside Molbee’s shop, visible from outside. I can’t remember how the front opened, but they were definitely visible, and in my mind they had entered from the front. Further back in the building I remember it becoming somewhat less shiny, and more oil smelling like all real small car places. I recall dad chatting to Molbee, and him showing me the remains of a car piston that had exploded. This was when I was doing O level physics, so would have been about 1973. I can’t remember anything about Molbee himself except that he was pleasant to chat to.

[...] Molbee had been telling dad about ‘good cars’ for years, but they were generally outside our range. Eventually we bought an Austin A40 Farina from him [...] for 60 pounds. [...] After about a decade of family use and camping expeditions it was sold for scrap for... 60 pounds.

At some point Mr Molbee acquired a site on Kidderminster Road, just around the corner from London Road, which he used as a repair shop and possibly also a petrol garage. This may have been a replacement for his previous works premises on Oakwood Place; it was certainly a lot closer to his showroom at number 212.[16]

Around the mid-1970s Mr Molbee disposed of both his West Croydon properties. The Kidderminster Road site was bought by Derek Stoner, who retained the name of Molbee Motors and continued to run it as a repair shop; it’s still there today, now in the hands of Derek’s son Mark.[17]

1970s–1980s: C & G Booth and the B Newton Motor Company

212 London Road, on the other hand, was taken over by C & G Booth Co Ltd, a car dealership that had previously been at 115 Lower Addiscombe Road.[18] C & G Booth remained for only a few years, and by late 1980 the premises were in the hands of the B Newton Motor Company. This company, which was founded in South Norwood in the 1960s, seems to have used 212 London Road mainly as a motorbike dealership, complementing its main premises at 247 Selhurst Road. By the mid-1980s it too had departed, taking on larger premises across the road on the ground floor of Zodiac Court.[19]

1980s–1990s: London Video & Food Centre

Next to arrive was the London Video Centre, a video shop which gave itself the rather grand description of “worldwide film manufacturers & distributors”. Trade was perhaps less lucrative than the proprietor had imagined, since a few years later the video cassettes were relegated to the back room to make space for a small supermarket in the front. This also seems not to have taken off to any great extent, as by early 1993 both videos and groceries had departed and the premises lay vacant.[20]

1990s: Trident Windows and Grange Care

By early 1995, number 212 was once again occupied, this time by double-glazing firm Trident Windows.

It seems likely that this was the same Trident Windows which had its factory just behind the historic Croydon Airport site on Purley Way and described itself as “Croydon’s largest privately owned window company”. Promising “direct from the factory prices”, it offered windows, doors, conservatories, and porches “made to measure to any style or size”, including “authentic box sash sliding windows” in hardwood and both standard and custom stained glass and leading. Any necessary building work was carried out by its in-house subdivision Trident Builders.[21]

Trident Windows remained at 212 London Road until around the start of 1998. but by mid-1999 had vanished entirely from Croydon phone books.[22]

Its replacement on London Road was Grange Care, an ancillary care company specialising in domiciliary care, day care, and end-of-life support for older people. This too remained only a short while, and was gone by the start of 2001.[23]

2000s–present: Spice Land

The streak of short-lived occupants was finally broken with the arrival of Spice Land. This Sri Lankan and South Indian restaurant was in place by the end of 2002, and remains there today.[24]

Aside from slight changes in price, the menu has remained remarkably consistent over the years: “short eats” such as fish cutlets, mutton rolls, and chicken 65; devilled items including squid and potato; kotthu (chopped flatbreads stirfried with ingredients such as egg or mutton), pittu (a steamed savoury cake made with ground rice and coconut, served with curry), string hoppers (thin noodles), dosas (thin, crisp pancakes served with chutneys), biryani, grilled meats, and a large selection of curries.[25]

Thanks to: David Godfrey and N M Godfrey; Mark Stoner; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers Bec and bob. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

- Quotation taken from advertorial on page 5 of the 20 December 1902 Croydon Chronicle (“Christmas in Croydon”). This is also the source of my assertion that Davies Bros arrived in late 1902; Ward’s 1903 directory, the data for which were finalised in the last week of November 1902, lists the property as “Unoccupied”. The advertorial gives no address other than “Royal Parade”, but an advert on page 3 of the same issue places Davies Bros at 4 Royal Parade (later renumbered to 212 London Road).

- Quotations taken from advert on page 3 of the 20 December 1902 Croydon Chronicle. Ward’s 1904 directory (the data for which were probably finalised in the last week of November or first week of December 1903) once again describes the property as “Unoccupied”.

- Ward’s directories list the City Boot Company from 1907 to 1916 inclusive.

- Quotations are taken from a report on page 2 of the 10 August 1907 Croydon Chronicle (“Caused a row at a shop”). The drunken customer was Richard Avery of Dennett Road; he was brought before the Borough Police Court and fined 4 shillings including costs (£24.24 in 2019 prices).

- Ward’s directories list Thorpe & Goddard Ltd, gen[eral] clothiers, at 212 London Road from 1928 up to the final edition in 1939. The company also appears (as “Outfitters”) in the October 1927 London phone book (but not the edition for the preceding April). Names of the company directors are taken from two newspaper articles; Alfred Richard Thorpe’s and Francis Goddard’s from “A director’s death”, Belfast Telegraph, 8 May 1936, page 10, and Mr Planner’s from “£5,000 claim: action against Croydon firm”, Portsmouth Evening News, 18 May 1938, page 9. I haven’t been able to find out Mr Planner’s first name. Information on office and workshops is taken from an article on page 15 of the 1 November 1930 Croydon Advertiser (“London Road fire”). Information on dyeing and cleaning is taken from an advert on page 7 of the 15 November 1930 Croydon Advertiser (reproduced here).

- Information and quotations regarding the fire are taken from “London Road fire”, as above.

- Quotations are again from “London Road fire”, as above.

First quotation is taken from “Poison mystery in Croydon”, Croydon Times, 9 May 1936, page 9. Second is from “Revelations follow death of secretary”, Croydon Advertiser, 9 May 1936, page 7. An article reporting on nine plaintiffs’ action to recover from Thorpe & Goddard the £5,127 they had paid for “bogus shares in the company” gives Mr Justice Singleton’s comments: “[...] of the three directors, Mr. Goddard knew nothing about the business, and was content to leave the management to someone else. Mr. Planner, who was 80 when he died in 1936, had been in failing health” (“£5,000 claim: action against Croydon firm”, as above). Another article added further comments: “If the directors were content to leave the management of their company in the hands of one of their number and do little more than draw their directors’ fees they could not complain if he led them astray.” (“Sale of non-existent shares”, Worthing Herald, 20 May 1938, page 13).

Francis’ trust in Alfred may have come partly from their long-standing connection. According to “Poison mystery in Croydon”, Francis’ son was married to Alfred’s daughter, and according to records of the Parish Church of St Stephen, Norbury, this marriage took place in 1921, 15 years before Alfred’s death.

- Information on Francis’ discovery of the fraud is taken from “Revelations follow death of secretary”, as above, which states that Francis talked to the police “about a week” before Alfred’s death. First quotation is taken from “A director’s death”, as above, and second is from “Brought home dying: 2/- left”, Daily Herald, 8 May 1936, page 3.

- Information and quotations are from “Poison mystery in Croydon”, as above.

- First quotation is from “Poison mystery in Croydon”, as above; second and third are from “Revelations follow death of secretary”, also as above.

- Address of 10 Beechwood Avenue is taken from “London Road fire”, as above, and confirmed by Alfred’s entry in the National Probate Calendar. The latter gives his assets at death as totalling £1388 9s 1d, which likely includes the value of his house and in any case is significantly less than the amount he was said to have stolen. His house can be viewed on Google Street View (the white one in the middle with a skip in the garden). Information on the two shillings remaining from £100, the loss of coat and watch-and-chain, and the loan from the taxi-driver is from “Revelations follow death of secretary”, as above.

- Information on court judgement is taken from “£5,000 claim: action against Croydon firm”, as above. Information on liquidation is taken from a notice on page 5010 of the 2 August 1938 London Gazette.

- The October 1949 London phone book lists Molbee Motors, Showrooms, at 212 London Road, along with “Works” at Oakwood Place, Thornton Heath. The firm’s earliest phone book entry is in May 1946, when it appears at Oakwood Place alone. Other details are taken from an advert found as a clipping in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon, which has “1963” written on it in pen and describes Molbee Motors as a “retail Ford dealer” and “Specialists in Low Mileage Used Cars from £100 [£2,110 in 2019 prices]”.

- Via email, 29 January 2020. I have corrected a few minor typos.

- Mark Stoner, who operates a car repair business at the Kidderminster Road site today (still under the name of Molbee Motors) tells me that he has no personal knowledge of the older version of Molbee Motors, but that over the years he’s been told by his customers that the Kidderminster Road site and 212 London Road once had the same owner, and that while number 212 was a showroom, Kidderminster Road was a petrol station and repair shop (via email, 29 January 2020).

- Mark Stoner tells me that his father owned Molbee Motors Ltd from the mid-1970s until 1993, and that he now owns Molbee Motors (“Not limited”) (via email, 29 January 2020). According to Companies House, the directors of Molbee Motors Ltd are Derek and Janet Stoner.

- Phone books list C & G Booth Ltd, Car Sales, at 115 Lower Addiscombe Road in February 1975 and C & G Booth Co Ltd, Mtr Dlr [Motor Dealer], at 212 London Road from January 1976 to January 1979 inclusive. The company is absent from Croydon phone books after this. According to a mid-1973 planning application for “positioning of an enlarged window to flank wall of existing car showroom” (viewed on microfiche at Croydon Council offices, ref 73/20/1315), the “C” of C & G Booth was likely Christopher Booth, who is listed as the applicant.

- See my article on Zodiac Court for more on the B Newton Motor Company. Regarding the company’s use of number 212, Brian Gittings’ 1980 survey of central Croydon describes its business there as “Motor Bikes”.

Croydon phone books list the London Video Centre in 1987, 1988, and 1990, and the London Video & Food Centre, Supermarket, in 1992. Description as “worldwide film manufacturers & distributors” is taken from headed paper used to write a letter to Croydon Council, included in the records of a planning application from 1989 (ref 89/455/P). A floor plan in an earlier planning application deposited in December 1985 (ref 85/3094/P) confirms that the video shop occupied both the front part and the back part at that point, while a photo of the side elevation included in the records of a later application granted in September 1993 (ref 93/1704/P) shows that the front part had a sign reading “Supermarket” while the “London Video Centre” sign was further back; this suggests that the supermarket was in the front and the video shop at the back. This latter application describes the present use of the premises as “retail outlet — vacant. Early 1993 ceased.”

There may also at some point have been a private pool club at the very back of the premises. A planning application for this was granted on 13 February 1986 (ref 85/3094/P), and a letter included in the records gives the name of “Croydon Pool Centre”. However, I’m not sure whether this ever opened; certainly it never seems to have appeared in the phone book.

- Quotations, address of 7 Imperial Way, Croydon, and information about in-house builders are all taken from a photocopied newspaper advert (annotated “CRO. LEADER 27/12/1990”) and an advertising leaflet (annotated “?1992”) found in the firms files at the Museum of Croydon.

- Croydon phone books list Trident Windows, double glazing, at 7 Imperial Way in July 1993 and then at 212 London Road in January 1995, July 1996, and January 1998. The company is entirely absent from the July 1999 edition.

- On 24 February 1998, “Grangecare [sic] (NI) Plc” was granted planning permission (ref 98/0066/P) for “use of ground floor [at 212 London Road] for purposes within class A2 (professional and financial services)”. Grange Care Plc is listed at 212 London Road in the July 1999 Croydon phone book, but absent from the January 2001 edition. Note also David Godfrey’s photo from late 1999, reproduced here, which shows a “To Let” sign over Grange Care’s own sign. David thinks this photo was probably taken between August and November 1999, most likely towards the November end. Information about what Grange Care actually did is taken from an advert on page 46 of the 22 January 1995 Sunday Life; this does not mention London Road, but is headed “Grange Care (NI) Plc” so is clearly the same company.

- Croydon phone books list Spice Land at 212 London Road from 2002 onwards. From personal observation, it was still open in early March 2020. The branding appears to have changed slightly over the years; when I moved to West Croydon in July 2011 it was definitely “Spice Land”, but it now seems to have run together as “Spiceland”. I’ve standardised on “Spice Land” throughout this article.

- Lists of dishes taken from menus collected in January 2011 and April 2017; see my photos (January 2011 page 1, January 2011 page 2, April 2017 page 1, April 2017 page 2.

- This was not the most recent thing I ate from Spice Land, but it’s the most recent thing I took a photo of. I had been planning to go for another dinner there closer to the time of publishing this, and had also been trying to catch the manager at a non-busy time in order to ask a few questions about the business, but the spread of Covid-19 to London made both of these things impossible.