The corner property at 182 London Road is currently occupied by James Chiltern, a firm of estate agents originally founded in 2007, while next to it at number 184 is a taxi firm, RB Minicabs.

Although now separate, numbers 182 and 184 were originally a single property, and so I’ll be discussing them together. This article covers their history up to the point where they were split, and my next article will continue the story to the present day.

1860s–1870s: Construction of Kidderminster Terrace

The short terrace comprising 182–204 London Road, which lies between Kidderminster Road and Royal Mansions, was constructed in the 1860s–1870s on land that had previously been part of the Oakfield Estate. This estate, which at its peak encompassed over 11 hectares, was broken up and sold off to developers after the death of its last owner, Richard Sterry, in February 1865.

Richard’s house, Oakfield Lodge, survived and later became Croydon General Hospital, but most of its extensive grounds were soon built over with new houses fronting on similarly-new side roads such as Oakfield Road and Kidderminster Road. By May 1866, Kidderminster Road had been laid out as “a new 40-ft. road”, with plots along both this road and London Road up for auction, and by October 1867 the first of what would eventually be six properties comprising 1–6 Kidderminster Terrace (later renumbered to 182–204 London Road) had been constructed.[1]

1860s: Construction of the Duke of Cornwall

Several conditions were imposed on the developers who bought the various plots on the Oakfield Estate; for example, while the plots fronting on London Road were “intended for private houses or shops”, those fronting on Oakfield Road and Kidderminster Road were reserved for “private houses only”, with “[n]o trade or business whatever [...] to be carried on, on any part of the land”.

Two plots were specifically set aside for taverns — one “contiguous to the Junction of Wellesley and Whitehorse Roads with St. James’s Road”, and the other at the corner of Kidderminster Road and London Road. Moreover, it was stipulated that except for these two plots, “No tavern, public house, inn, or beershop, shall be erected, nor shall the business of a licensed victualler or seller of beer, wine, or spirits, be carried on, in or upon any house to be erected upon any lot”.[2]

The first occupant of the newly-constructed 1 Kidderminster Terrace was thus the Duke of Cornwall, which was open by early 1869 under the stewardship of Robert Cliff. Although technically merely a beerhouse — Croydon magistrates repeatedly refused it a licence to sell spirits — it had “stabling room for 24 horses, including five loose boxes and three coach houses, together with eight bedrooms for guests”.[3]

1870s: George and Sophia Hunt

By 1872 the Duke of Cornwall was in the hands of George and Sophia Hunt, a married couple who had previously run the Conquering Hero on Beulah Hill, Upper Norwood.[4]

Sophia was George’s second wife, and only in her early twenties — half his age — but George had at least a decade’s experience of tavern-keeping at this point. With his first wife, Caroline, he had run another Norwood pub, the Beulah Retreat, for five years during the first half of the 1860s before acquiring the freehold of the Conquering Hero and spending over £2,000 (£239,000 in 2017 prices) on improvements including a new stables.[5]

George’s time at the Conquering Hero appears to have been beset with difficulties. Its location next to the Crown Pond may have been a picturesque one, but there was soon “trouble with the authorities” as “seepage from the urinals and cellars” entered and fouled the pond. Moreover, “disturbance to the ground level” caused by the subsequent construction of a rival beerhouse next door led to “flooding Hunt’s pub with rain water”.

This new beerhouse, the Fountain Head, was built and run by another pair of Norwood publicans, Henry and William Preddy. According to local historian John Coulter, this “short-lived parasitical establishment” had as its “sole purpose [...] the harassment of poor George Hunt”. By 1871, George had begun the process of relinquishing the freehold of the Conquering Hero, and by July 1872 his pub was in the hands of the Preddys. The Fountain Head, having served its purpose, was closed.[6]

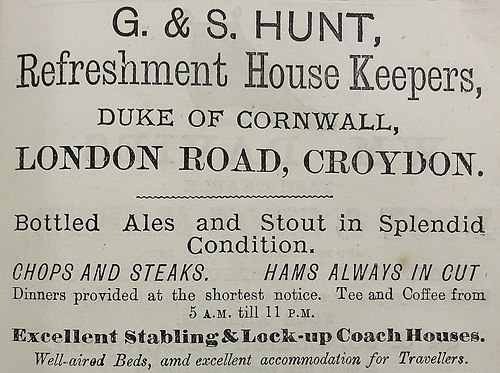

George and Sophia must have hoped for a rather better time at the Duke of Cornwall. As well as “Bottled Ales and Stout in Splendid Condition”, they offered tea and coffee from 5am until 11pm, “Dinners provided at the shortest notice”, and “excellent accommodation for Travellers” including “Well-aired Beds”. Indeed, when the Bath and West of England Agricultural Society held its annual show at Croydon in May 1875, George placed a special advertisement in the Croydon Advertiser, urging attendees to make use of his “Good Beds and Refreshment”.[7]

Despite all these efforts, the Hunts’ stay at the Duke of Cornwall was limited to just a few years, as George died here on 31 July 1875 at the age of only 48. Seven months later, Sophia married John Richard Blackmore at Croydon Parish Church, and at the next annual licensing meeting of the Croydon Petty Sessional division on 2 March 1876, the magistrates agreed to transfer the licence of the Duke of Cornwall from Sophia to Thomas Benson. Sophia remained in the pub trade, however; by 1881, she and John were running the Robin Hood in Penge.[8]

1870s–1880s: Several landlords, and possibly a new leaseholder too

The turnover of landlords was relatively rapid over the next decade, as Thomas Benson was replaced in turn by John Freebody, Sam Waghorn, Thomas Waghorn, Thomas Morum, and G A Burtwell.[9]

Thomas Waghorn would have reason to remember his time here despite his short tenure, thanks to one of his grandchildren — a “little girl” who inadvertently caused him to be summoned to Croydon Police Court for allowing drunkenness on the premises. The court heard that at 12:50pm on 26 May 1881, a police sergeant entered the Duke of Cornwall to see “a man sitting down in front of the bar drunk” with “the best part of a pint of ale on the counter.”

Thomas’s defence against the charge was that since he and his wife Mary had both had to attend to errands elsewhere, his granddaughter had been left “in the bar, with instructions to call her grandmother if anyone came in. But instead of doing so, when the man in question came in, the little girl served him, no doubt thinking she would like to draw the beer.” Indeed, she even served “a woman and also a girl with some ale” while the police officer was on the premises! Unsurprisingly, the magistrates decided this was no excuse, and fined Thomas 20 shillings plus 13 shillings in costs (a total of £191 in 2017 prices).[10]

The Duke of Cornwall continued to provide accommodation throughout this time, to both short-term visitors such as travellers and longer-term lodgers such as labourers and even tradesmen.[11] The stables remained in use, too, offering changes of coach horses as well as accommodation for travellers’ own animals.[12]

It may also have been around this time that Watney’s, a long-established firm of brewers, took on the leasehold of the premises. This firm already had a Croydon connection in that its patriarch, James Watney, had been resident at Haling Park in South Croydon since at least 1851.[13]

1880s–1890s: Henry Woods

The longest-serving landlord of the Duke of Cornwall was also the one who would ultimately be responsible for its demise. Born in Wiltshire in 1842, Henry Woods joined the Navy as a ship’s cooper at the age of 22 and remained in service for the next two decades.[14]

After leaving the Navy, Henry moved to Sittingbourne in Kent, where he supplemented his naval pension by entering the licensed trade. He arrived on London Road around 1888, replacing G A Burtwell, and continued to run the Duke of Cornwall until just before the turn of the century.[15]

February 1898: “Heavy fines and a lost license”

In February 1898, Henry appeared before the Borough magistrates, having been “summoned under section 15 of the Licensing Act of 1872 for permitting his premises to be used as a brothel on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, and 24th January”. This was a serious charge, since if Henry was convicted, not only would he lose the license he held for the Duke of Cornwall, but he would be “disqualified for evermore from holding a license”.[16]

The case rested on police observations over several days, with various police officers reporting events such as those which occurred on 21 January:[17]

At a quarter to nine on that day a female he [the police observer] knew as a loose character entered the house with a man by the side door in the Kidderminster-road. The man left at nine o’clock and the woman shortly after. A little later another woman of the same class accosted a man in the London road, went to the house, entered the bar and had some drink, and spoke to a woman behind the bar. They then went round to the private door and knocked. It was opened by someone, he could not tell who, and they went in.

Henry told the magistrates that although he “was aware women of loose character used his house for the purposes of refreshment”, he “had no ‘touts’ in his employ [...] but he was aware there were such men acting for loose characters in the district. He absoutely denied that the house had ever been used for the purpose suggested”.[18]

Henry’s statements were supported by Stephen Jackson, a Watney’s employee who “said it was part of his duty to visit the houses belonging to the firm. [...] The house was always conducted in the most orderly manner, and was kept exceedingly clean and well. Had he had any doubt about defendant’s character, he would at once have given him notice to quit.”[19]

Watney’s lawyer, Mr Colam, was also present in court, and rather less supportive than Stephen, appearing to be quite happy to sacrifice Henry in order to persuade the magistrates to convict under Section 14 of the Act rather than Section 15; this would result in a fine for Henry but no loss of the license. Addressing the court “on behalf of Messrs. Watney”, he noted that:[20]

“these women had been admitted to a part of the house to which they should not have been admitted. Whatever the result of this case, Messrs. Watney would get rid of this tenant, and in case of the license being renewed they would suggest to the Bench that that part of the house should be excluded from the licensed part. [...] Messrs. Watney would take immediate steps to find a new tenant, and he asked the Bench to adjourn the case in order that they might find a tenant and apply to the magistrates for a protection order to save the license from lapsing altogether.”

The magistrates, however, not only found the evidence against Henry generally convincing, but declined to grant Mr Colam’s request. Because “the character of the woman who was seen to enter [on the 23rd] was not known”, Henry was given the benefit of the doubt for that day, but the Bench came to “the conclusion to convict on the summonses for the 21st, 22nd, and 24th”. Henry was fined “£5 with 12s 6d costs, and £1 1s, solicitor’s fee, in each case” (a total of £2474 in 2017 prices) and the Duke of Cornwall was “closed forthwith”.[21]

![A notice addressed “To the Overseers of the Poor of the Parish of Croydon, in the Borough of Croydon; to the Superintendant of Metropolitan Police of the W Division; and to all whom it may concern” stating that “George Baines, now residing at 214 Whitehorse-lane” intends “to apply at the Adjourned General Annual Licensing Metting [sic] for the Borough of Croydon [...] for a License authorising me to apply for and hold an Excise License to sell [beer and wine] by retail, to be consumed either on or off the premises, at my home and premises called the ‘DUKE OF CORNWALL,’ 62, London-road”.](/history/images/0182/george-baines-notice-500px.jpg)

March 1898: A license refused

Undeterred, Watney’s rapidly found a new prospective tenant. On 5 March, a notice appeared in the Croydon Guardian stating that George Baines, “now residing at 214 Whitehorse-lane, in the Parish of Croydon”, intended to apply for a license to serve beer and wine at the Duke of Cornwall.[22]

At the licensing meeting held later the same month, however, the Croydon Borough Magistrates were presented with a “memorial” opposing the application, signed by over 50 “influential and important persons” who “lived within 250 yards of the site in question”.[23]

The representative of these persons, Mr Blaiklock, stated that there were already “plenty of licensed houses in the neighbourhood”, that “as a licensed house this place was useless and unnecessary”, and that “the people of the neighbourhood were strongly opposed to the grant being made”. The magistrates decided to refuse the application, and additionally to refuse Watney’s last-ditch plea to be allowed to use the premises as an off-licence.[24]

Watney’s were now left with the leasehold of a property they were no longer permitted to use for the sale of beer.[25] Their solution to this, and the remaining history of 182–184 London Road up to today, will be covered in my next article.

Thanks to: Alison Kenney at the City of Westminster Archives; Ewan Munro; Mark Ballard at the Kent History and Library Centre; Stephen Richards; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-readers bob and Kat. Census data and FreeBMD indexes consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

Quotation re Kidderminster Road is taken from the particulars for a sale of Oakfield Estate building plots on 24 May 1866 (DCXIV in the 1865–66 Harold Williams volume at the Museum of Croydon). A plan included in a later sale of other plots on 24 October 1867 (Museum of Croydon drawer 39 map 12) shows a building at the north corner of Kidderminster Road and London Road. None of the other buildings which later became part of Kidderminster Terrace appear; their sites are shown as empty plots.

For a visual representation of the relation between Kidderminster Terrace and the rest of the Oakfield Estate land, see the excerpt of the 1800 Inclosure map which appears as the second image in part 1 of my Zodiac Court mini-series; the overlay of modern roads makes it clear that Kidderminster Terrace was right up at the northern edge of the estate (which at the time of that map was owned by “Mrs. Eliz. Panton”).

Quotations in this and the previous paragraph are taken from the abovementioned 24 May 1866 sales particulars and the particulars of an earlier sale on 17 November 1865 (DCIX in the 1865–66 Harold Williams volume at the Museum of Croydon). The first-mentioned tavern plot was included in the 1865 sale, and the second-mentioned in the 1866 sale. Confirmation that these two plots were the only ones reserved for taverns (and indeed allowed to have taverns upon them) comes from a report on Croydon magistrates’ annual licensing meeting on page 7 of the 9 March 1868 Morning Advertiser, which states that “the Oakfield estate was restricted to two tavern plots”.

The tavern at the corner of Kidderminster Road and London Road is the subject of the present article. The one at the Wellesley Road junction was the Oakfield Tavern (modern address 166 St James’s Road); see its mention in the annual licensing committee report on page 7 of the 8 March 1869 Morning Advertiser.

Quotation re accommodation is taken from a long article on page 2 of the 15 March 1873 Croydon Advertiser, which adds that the Oakfield Tavern (the other tavern built on Oakfield Estate land) had “accommodation for neither horse nor man”. The article also states that the Duke of Cornwall was “a house that has never been licensed for the sale of spirits”, an assertion borne out by earlier articles in the Morning Advertiser reporting on refusals of a licence (e.g. 9 March 1868, page 7, 8 March 1869, page 7, 7 March 1870, page 6). All three Morning Advertiser articles name Robert Cliff as the man in charge of the Duke of Cornwall, and Robert is also named in its listing in Warren’s 1869 street directory. Regarding the date of opening, it’s unclear whether it had already opened by the time Robert applied for a licence in 1868, but it was certainly open by the time he reapplied in 1869, as the relevant article states that “The Brighton coach had stopped there, and would stop again.”

Regarding the “stabling room for 24 horses”, see my photo of the yard behind the property. The cobbled entrance to this yard could well be original. On the right of the photo is a decent-sized building now occupied by Molbee Motors; I suspect this of being the site of the Duke of Cornwall’s stable block, and it’s possible that part of the present actual building used to be part of the stable block. A plan included in the particulars for a sale of Oakfield Estate land plots on 17 June 1869 (ref CR2744 at the Museum of Croydon) shows a building in this position, though of different shape, and looking at the brickwork today suggests that the easternmost part might be original while the westernmost part is a later extension.

Wilkins’ 1872–73 directory lists G & S Hunt, refreshment house keepers, at the Duke of Cornwall (see also the advert reproduced here). Ward’s 1874 directory omits “S”, but gives “G”’s full name as “George”, as does an 1875 report on George’s being assaulted by a labourer who had stolen a bottle of ale from the pub (“Charge of Assault”, 16 January 1875, Croydon Advertiser, page 3. George’s entry in the National Probate Calendar gives his wife’s full name as Sophia Ellen Hunt. The 1871 census lists George and Sophia E Hunt at the Conquering Hero “Public Ho” on Beulah Hill.

The Duke of Cornwall had at least one other landlord between Robert Cliff and George Hunt. The handwriting on the 1871 census entry for the pub is quite hard to read, but lists ten people in the household, including 26-year-old “Beer & Wine Retailer” Edward or Edmund possibly-Sawyer, his 25-year-old wife (possibly called Amelia), three children aged 1 month, 1 year, and 3 years, and servants including a housekeeper and potman.

- The 1871 census gives George and Sophia’s ages as 42 and 21 respectively. According to Surrey parish registers, George Hunt, a widower and “Licensed Victualler” living in Norwood, married spinster Sophia Ellen Stevens at All Saints, Upper Norwood, on 13 November 1870. The 1861 census shows George and Caroline Hunt at the “Retreat Beer Shop” on Beulah Hill. According to a report on Croydon magistrates’ annual licensing meeting in the 4 March 1865 Croydon Times, describing among others George Hunt’s application for a licence for the Conquering Hero, “The applicant had spent more than £2,000 on improving the premises which were his own freehold. He had provided ample stabling and standing for nine horses. He had kept the Beulah Retreat for five years and had not one single complaint.” A report on page 2 of the 6 March 1865 Morning Advertiser confirms that the Conquering Hero was George’s “own freehold from the trustees of the waste lands of Croydon” and that the licence was granted with “no opposition”.

Information and quotations regarding seepage, flooding, and the Fountain Head all taken from Images of London: Norwood Pubs by John Coulter.

It’s unclear exactly when and how George decided to leave the Conquering Hero. As already noted, the 1871 census (which was conducted on the night of 2–3 April) lists George and Sophia in residence at the pub, but an advertisement on page 8 of the 7 February 1871 Morning Advertiser states that “Messrs. Daniel Cronin and Sons have received instructions to offer for Sale by Public Auction, shortly, a lease for eighty years at a rental of fifty pounds [£5599 in 2017 prices] per annum” of “The Conquering Hero, Beulah-road, Lower Norwood”. It’s possible that this advertisement was intended mainly to find out whether there would be anyone interested in acquiring such a lease, before going to the trouble of setting one up. Another possibility is that George had sold the freehold on to someone else, leased it back, and then decided to leave after all. In any case, a similar advertisement on page 8 of the 12 September 1871 Morning Advertiser instead offers “the freehold of the above valuable property”. Date by which the Preddys had taken over comes from a report on the meeting of the Croydon Local Board of Health on page 3 of the 6 July 1872 Croydon Advertiser, which includes mention of a letter “from Mr. Preddy, of the Conquering Hero, Crown-road, asking to be allowed to purchase a small quantity of the Crown Pond land [...] in order to improve the approach to his stables”.

All quotations except the final one are taken from the 1872–3 advert reproduced here. The final quotation is taken from an advert on page 4 of the 29 May 1875 Croydon Advertiser, which is headed “Bath and West of England Show”. According to an article on page 23 of the 5 June 1875 Illustrated London News, the reason for this seemingly geographically-anomalous show being held in Croydon was that “some time ago” the Bath and West of England Agricultural Society had merged with the Southern Counties Agricultural Association, and hence the annual show rotated between southern, central, and western England. The article notes that the show opened on Monday 31 May near the railway station at Waddon, and an illustration of it can be seen on the previous page.

George and Sophia’s previous experience at the Conquering Hero — which, as made clear by the letter from “Mr. Preddy” referenced in an earlier footnote, was itself within the purview of the Croydon Local Board of Health — does suggest that they were being economical with the truth when they wrote to the Board in August 1873 to apologise for erecting an unauthorised sign on the footpath in front of the Duke of Cornwall. Claiming to be “a London firm” and thus in “ignorance of the bye-laws”, they stated that they “had not the slightest intention of breaking the rules of your Board”, and asked “that the post already erected might remain without prejudice to the interest of the public.” The Board, however, noted that the post was “a very serious inconvenience, as it was on the public footpath, which was narrow at this particular spot”, and resolved that “the parties be required to remove the objectionable post”. (See the Local Board of Health report on page 2 of the 16 August 1873 Croydon Advertiser.)

- George’s age, place, and date of death are taken from his entry in the National Probate Calendar. Information on Sophia’s marriage to John Blackmore is taken from Surrey parish registers; note that Sophia Ellen Hunt is described as a widow, and her father’s name is a match to the above-cited parish register entry for her marriage to George. The 1881 census shows John and Sophia at “The Robin Hood” in Penge; he is listed as a “Publican” and her age and place of birth are a match to her entry alongside George in the 1871 census. Information on transfer of licence from Sophia to Thomas is taken from an article on page 3 of the 4 March 1876 Croydon Advertiser.

- Ward’s directories list Thomas Benson in 1876, John Freebody in 1878, J S J Waghorne [sic] in 1880, T Morum in 1882, Thomas Morum in 1884, — Burtwell in 1885, and G A Burtwell in 1886, 1887, and 1888. The 1881 census lists Thomas Waghorn. “J S J Waghorne” may have been the same person as the Sam Waghorn mentioned in the 1878 advert reproduced here and/or Thomas Waghorn’s son Samuel John Waghorn (as listed alongside each other at Great Chart, Kent, in the 1861 census).

- Quotations in these two paragraphs are taken from an article on page 3 of the 11 June 1881 Croydon Guardian (“Permitting drunkenness”). Other information also taken from this article, aside from Thomas’s wife’s name, which comes from the 1881 census, and the fact that Thomas’s tenure was short (see previous footnote).

- The 1881 census lists 12 lodgers, comprising 8 travellers, 2 labourers, 1 butcher, and 1 stableman; the latter was likely the pub’s own stableman. Contemporary newspaper reports also mention lodgers “living at the Duke of Cornwall”, including “George Dinnage, labourer”, who “was charged with being drunk and incapable in the Selsdon-road, Croydon” in March 1876 (Croydon Advertiser, 4 March 1876, page 3).

- According to an article on page 5 of the 9 June 1877 Croydon Advertiser, on Saturday 2 June 1877 “the Brighton Coach was started from London for the opening of the season. At Croydon it changed horses at the Duke of Cornwall stables, and when the fresh horses arrived at West Croydon railway bridge [around 400m down the road] the leaders, being startled by the steam and noise of a train passing under the bridge, took fright, swerved round towards Tamworth-road, and ran the coach into the cabman’s shelter, moving it bodily several feet. A cabman who was lying on one of the seats in the shelter was very much startled and rushed out in great alarm.”

According to Walter Pearce Serocold’s The Story of Watneys (1949, p 25), prior to 1880 most licensed houses in and around London were “held on lease by publicans, who borrowed from brewers the money needed” to pay the freeholder for their lease, with one of the conditions of such a loan being that “The publican in return tied the trade to the lending brewer”; that is, the publican would purchase beer solely from that brewer. However, during the 1880s “loans became obtainable from other [...] sources”, and so “brewers found it necessary to enter the field themselves as buyers of freeholds or leaseholds to secure their trade”.

Despite the above, it should be noted that I have no direct evidence that Watney’s acquired the Duke of Cornwall lease during the 1880s. Watney’s archives are held at the City of Westminster Archives, and the archivist there tells me that they have no registers of leasehold pubs prior to 1905 (via email, 23 November 2017). Watney’s certainly had the leasehold by 1898, as a newspaper article published that year describes that company as having 23 years left on the lease (“A Croydon beerhouse”, Croydon Advertiser, 19 February 1898, page 2).

James Watney is listed at Haling Park in Croydon street directories from the 1850s onwards, including Gray’s 1851, which was the first comprehensive directory to be published. He and his wife Rebecca also appear there in the 1851, 1861, and 1881 censuses (the 1871 census lists them at 32 Prince’s Gardens, Westminster, which according to James’ entry in the National Probate Calendar was their other residence). For more information on James Watney, see The Red Barrel: A History of Watney Mann by Hurford Janes (1963), in particular page 132 for the Haling Park connection.

- The 1891 census entry for the Duke of Cornwall lists 48-year-old Henry Woods, licensed victualler, born in Anstey [sic], Wiltshire, along with his 33-year-old wife Frances, seven lodgers, and a 16-year-old potman. His service record gives his date of birth as 20 September 1842, and states that he entered the Navy on 22 February 1865 as a cooper on the Duke of Wellington, that his initial service was for a period of 10 years, and that in 1875 he renewed this for a further 10. The 1871 and 1881 censuses place him among the crews of HMS Monarch and HMS Vernon, respectively, both at Portsmouth.

Ward’s directories list Henry Woods at the Duke of Cornwall from 1889 onwards. An article on page 2 of the 19 February 1898 Croydon Advertiser (“A Croydon beerhouse”) describes him as “a Navy pensioner”, and another on page 2 of the 9 April 1898 Croydon Advertiser (“Croydon Borough quarter sessions”) states that at that point he “had been in the neighbourhood [i.e. Croydon] many years, having previously held a license at Sittingbourne”. I haven’t been able to find out the name or address of his establishement in Sittingbourne; I contacted the Kent History and Library Centre but unfortunately they tell me (via email, 4 January 2018) that there’s a gap in their county directories between 1878 and 1891, which covers the time Henry would have been there.

There is some confusion over Henry’s marital status both before and during his time on London Road. He seems to have married during his naval service, as the 1871 census lists him (on HMS Monarch in Portsmouth Dockyard) as single whereas the 1881 census lists him (on HMS Vernon in Portsmouth Harbour) as married; however, because he’s listed aboard his ship, his wife’s name is not included.

The 1891 census, by which point he was at the Duke of Cornwall, also lists him as married, to 33-year-old Portsmouth-born Frances. This may be the person he married while in the navy; it wouldn’t seem out of the question for him to have met her while his ship was docked at Portsmouth. Moreover, the 1881 census includes a 27-year-old Frances Woods, born in Portsea, married, and living in Portsea with her two sons Henry and Arthur. There is some discrepancy in age here, but it wasn’t uncommon for women to take a few years off their age for the census. It also seems that Henry Junior and Arthur would have had to have died between 1881 and 1891, but again this wasn’t uncommon at the time, and (although absence of evidence is not evidence of absence) I haven’t managed to find either of them in the 1891 census; I also haven’t been able to find any plausible Portsmouth-born Frances Woods other than the one living with Henry in Croydon.

“A Croydon beerhouse” (Croydon Advertiser, as above) states that the Mrs Woods as of 1898 had married Henry at the Registry Office on 6 December 1894 after divorcing her first husband, Mr Curtis, and that her maiden name was Cresswell. It also notes that her divorce from Mr Curtis was incomplete; she had been granted only a decree nisi, since “the Queen’s Proctor had intervened and the decree was not made absolute.” The FreeBMD Civil Registration Marriage Index for the last quarter of 1894 includes a marriage between Henry Woods and Frances Cresswell in Croydon (the other two people on the same page, Francois Lépidi and Mary MacLean, were married to each other according to Surrey parish registers, and hence Henry and Frances must also have been married to each other).

Given the abovementioned dodginess over divorce (and the fact that Mrs Woods’ marital status was even questioned in court in the first place), it seems worth asking whether the two “Frances”es were the same person. Perhaps Frances had actually been living with Henry as his common-law wife ever since Portsmouth; the census data listing her as his wife were, after all, supplied by the householders themselves, and no proof of marriage would have been asked for (see Making Sense of the Census Revisited, Edward Higgs, 2005, pp 17–19). If this was the case, though, it’s not clear why they decided to get properly married in 1894. One possibility is that “Mr Curtis” had died, and so the incomplete divorce had ceased to be a problem. However, the abovementioned newspaper article makes no mention of this, and indeed includes a note that “the witness’s legal position” was explained to her in court, which suggests to me that she was being informed that she was not legally married to Henry.

In any case, Frances seems to have left the picture by 1901; the census of that year shows Henry living in South Norwood with a new wife, 44-year-old Peckham-born Selina. (I should however mention that I’ve not managed to find any record of their marriage, so perhaps there was dodginess going on here too.)

Information and quotations taken from “Serious charge against a licensed victualler”, Croydon Guardian, 19 February 1898, page 3. The case is also reported in “A Croydon beerhouse”, Croydon Advertiser, 19 February 1898, page 2, from which the quotation in this section’s title is taken. The Croydon Advertiser article states that the prosecution was under Section 16 of the Act, as opposed to the Section 15 claimed by the Croydon Guardian, but according to a transcript of the Act the Croydon Guardian is correct.

Two of the three magistrates hearing Henry’s case also had a London Road connection. Samuel Rymer had lived in a house on the site where Lidl now stands from the early 1870s to the early 1880s, and Thomas Baddeley lived at 428 London Road from around 1880 to at least the time of Henry’s trial.

- “Serious charge against a licensed victualler”, Croydon Guardian, as above.

- “Serious charge against a licensed victualler”, Croydon Guardian, as above.

- “Serious charge against a licensed victualler”, Croydon Guardian, as above.

- “A Croydon beerhouse”, Croydon Advertiser, as above.

- “Serious charge against a licensed victualler”, Croydon Guardian, as above.

- Croydon Guardian, 5 March 1898, page 5, reproduced here.

- “The Duke of Cornwall refused”, Croydon Advertiser, 26 March 1898, page 3.

- “The Duke of Cornwall refused”, as above. (Henry Woods also appealed against the removal of his license, and was likewise refused on 5 April 1898; see “Croydon Borough quarter sessions”, as above.)

- As noted in an earlier footnote, “A Croydon Beerhouse” states that as of 1898 Watney’s held a lease with 23 years left on it.