Beydağı Food Centre at 83–85 London Road is an international supermarket focusing on Polish, Turkish, and Greek food.

1830s–1840s: Construction of the original building

As noted in my article on number 79, the current 5-property terrace numbered 79–87 is not the original construction on this piece of land, but rather a late 1890s replacement for a pair of mid-century semi-detached houses. I described the southernmost of these houses in that article. Here I discuss the other, which like its neighbour was built between 1835 and 1844 and owned by Henry Bance.[1]

1840s–1850s: J Lewland and Henry Lowman Taylor

The earliest documented resident was one J Lewland, in place by the time the 1844 Tithe Award survey was conducted. It’s not clear how long they remained here, or what their occupation was, if any.[2]

By 1851, J Lewland had been replaced by Henry Lowman Taylor, a wholesale ironmonger in his 40s who lived here with his wife Eliza and a couple of servants. Henry traded on Queen Street, off Cheapside, in the City of London, and was a member of the Common Council of the Corporation of London as well as chairman of the Corporation’s Markets Improvement Committee.[3]

Henry, in his capacity as a defender of London’s markets, even came to the attention of Charles Dickens. The latter, who appears to have supported the Times campaign for the removal of Smithfield Market, wrote to W H Wills in July 1850 describing Henry as a “wiseacre” and a speech he’d made to the Common Council as “a most intolerably asinine Speech about Smithfield”.[4]

Henry and Eliza departed London Road by 1853. He later became a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex and Deputy of Cordwainer Ward in the City of London, among other illustrious positions.[5]

1850s–1860s: William John Wilson; John, Anna, and Henry Pace

Next to arrive was William John Wilson, in place by 1853 but gone again by mid-1861, and leaving little trace in the documentary record.[6] His replacement was John Pace, a merchant in his 50s who lived here with his wife Anna Maria, son Henry, and daughter Amelia Charlotte. Henry Pace was a barrister, practising at 23 Old Square in Lincoln’s Inn.[7]

1860s–1870s: Jean Trieb

Around the middle of 1864, the Paces were replaced by recently-widowed 30-something Jean Trieb and his young daughter Catherine. Married just two-and-a-half years earlier, on Christmas Eve 1861, Jean lost his wife Elizabeth in early 1864. He and Catherine moved very soon afterwards from their home in Peckham to London Road.

Although born in Germany, Jean became a naturalised British citizen at some point between 1861 and 1871. He worked as a commercial agent, specialising in foreign goods. By 1871 he had married again and had another child, named Jean like himself. His new wife, Emilie, was French-born but again a naturalised British citizen; she was also 16 years younger than him. By late 1873, however, the Trieb family had departed from London Road.[8]

1870s–1880s: Leo Kerrel, Mrs Redding, John English, Albert Banister

The house continued to be used as a private residence up until its demolition in the late 1890s. Leo Kerrel moved in by December 1873, but was replaced very quickly by a Mrs Redding, who remained until around 1878. By the time of the April 1881 census, 60-something retired butcher John English was in place along with his wife Emma and daughter Ellen. John employed not only a general household servant but also a gardener; this is perhaps a reminder that at this stage the property was a semi-detached house with a reasonably-sized garden, though one does wonder whether the garden was really large enough to require a live-in gardener.[9]

The English family was gone by early 1886, replaced by Albert Banister. By 1891, several of Albert’s family members were living with him; his parents William and Thirza, in their 70s at this point, and his adult sisters Ellen and Harriett. The census of that year lists the entire family as “Living on [their] own means”; that is, they had investments or other income that meant they did not need to earn a living. However, like their neighbour, Dr Hugh Montgomery Smith, they were forced to move around 1896–1897, as both their house and Dr Smith’s house (the other half of the semi-detached pair) were demolished to make room for the new terrace that today is numbered as 79–87 London Road.[10]

1900s: The Original Scotch Stores Company; T Whillier, builder & contractor; William Jewell, umbrella maker and trading-stamp collector; and St Paul’s Printing Works

Construction of the five new shops was complete by the end of 1898. I’ve already described the history of the two southermost of these, in my articles on number 79 and number 81; here I cover the next two (numbers 83 and 85), and I’ll complete the story in my article on number 87.

First to arrive at number 83 was the Original Scotch Stores Company, in place by late 1899. It’s unclear whether this company was concerned with Scotch whisky or Scottish products in general, but in any case it was gone again by the end of 1901. Number 85 took slightly longer to find its first occupant; T Whillier, builder and contractor, arrived some time between late 1899 and late 1900, but was also gone by the end of 1901.[11]

The next two sets of occupants again stayed for only a short while. William and Elizabeth Jewell moved from 2 Clarendon Road to 83 London Road around mid-to-late 1901, along with their children Harold and Marion. William worked as well as lived on the premises, and was in business both as an umbrella manufacturer and a collector for a trading-stamp company; it’s not clear whether these two rather disparate professions were simultaneous or consecutive. However, he was issued with a bankruptcy-related receiving order in 1904 and by the end of that year had relocated to Fairholme Road (a side-street coming off London Road between numbers 347 and 355).[12]

Meanwhile, 60-something widow Elizabeth Bergman was in residence at number 85 by April 1901, along with her daughters Beatrice and Frances. It’s not clear whether the Bergmans were involved in the printworks — St Paul’s Printing Works — that was also in place on the premises by the end of that year; but, in any case, both Bergmans and printers had departed by late 1902.[13]

1900s: Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society

Next to arrive at number 85 was a branch of the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society. Founded in 1843, the Society was originally known as the Liverpool Independent Legal Victoria Burial Society, set up in order “to afford the poorer classes of the community the means of providing for themselves and their children a decent interment at the trifling expense of a halfpenny, a penny or three pence per week, according to the age of the member” (24p, 47p, or £1.42 respectively in 2014 prices) and thus “prevent the occurrence of those sad spectacles of inhumanity which so frequently distress the last moments of the dying poor and their sorrowing families”.[14]

A few words of explanation may be needed here, though the author of the quotation above clearly expected his audience to understand what he meant by “sad spectacles of inhumanity”. This would have referred to the pauper’s funeral — burial at the expense of the parish — which was generally an extremely perfunctory affair involving a common grave containing multiple bodies. Parish-funded burials had been going on since at least the 16th century, but between around 1750 and 1850 there was a shift in the way these funerals were viewed; they became “both terrifying to contemplate oneself and profoundly degrading to one’s survivors”, creating a “life-long stigma” for the latter.[15]

Despite being “started without any subscribed capital whatever, without any influence and with very little, if any, experience”, as early as 1845 the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society was paying out claims in Cork and Runcorn, and by 1847 was also collecting subscriptions in Chester, Warrington, Ormskirk, and Northwich.[16] By 1863 it was operating in Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and various parts of England, including a few outposts in London.[17] Indeed, in August 1884 the Society decided to move its headquarters to London, and acquired a building in St Andrew Street for this purpose; the final board meeting in Liverpool was held on 4 June 1885.[18]

The Society arrived at 85 London Road around 1902, and remained until around 1908.[20] It continued to exist and expand after leaving London Road, and is still around today under the name Liverpool Victoria (branded as LV=). Indeed, it has a office presence in Croydon, at the impressively mirrored 69 Park Lane, and advertises itself prominently on the platforms at East Croydon Station.

Late 1900s: Star Rubber Stores, Henry Besley, and E Seymour

Following William Jewell’s departure from number 83, the premises remained vacant until the arrival of Star Rubber Stores along with Henry Besley, watchmaker, around 1907. However, like the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society next door at number 85, both were gone again by 1909.[21]

Number 85’s next occupant also stayed only a short time; E Seymour, picture frame maker, was in place by 1910 but gone again by 1912. The premises then remained vacant for several years.[22]

1910s–1920s: Royal London Mutual Insurance Society

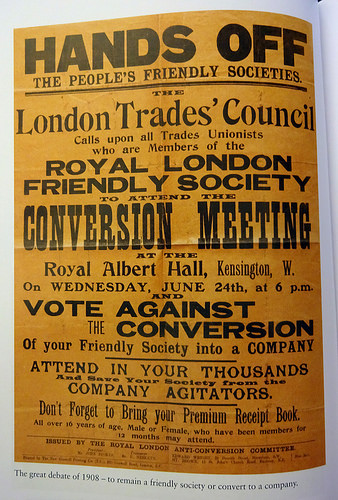

Number 83, on the other hand, soon found a new occupant which proved rather longer-lasting: the Royal London Mutual Insurance Society (previously known as the Royal London Friendly Society). This bore some resemblance to the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society; it was set up with similar aims, around the same time, and it also survives to the present day.

Its genesis, however, was in another of the friendly societies of the day, Royal Liver, having been founded in 1861 by three Royal Liver employees: Joseph Degge, William Hambridge, and Henry Ridge. All three men were in their early twenties at the time, and Royal Liver itself had been founded only a decade before, in 1850.

In his Royal London: The First 150 Years, Murray Ross gives several possible reasons for these young men’s decision to set up in competition with their employer: their objection to the Royal Liver rule that members in arrears would lose coverage until four weeks after they’d caught up with payments, Joseph’s concern over having chosen the losing side in a campaign for Royal Liver to convert from a friendly society into an company, or even just “the need to make a change [...,] to get out of the rut, and [...] to go into uncharted seas.” The new Society received its certification on 10 April 1861.[23]

In 1908, and in the face of some opposition from its members, it was converted from a friendly society into a mutual company — no longer subject to the specific legislation covering friendly societies, but still fully owned by its members.[24] It arrived on London Road just a year or so later, around 1910, and remained until around 1930.[25].

1920s–1960s: H J Searle & Son

Meanwhile, as mentioned above, number 85 remained vacant for several years after the departure of E Seymour. It was only occupied again around 1919, when furnishing and outfitting company H J Searle & Son expanded its business from number 87 next door. After Royal London left number 83 around 1930, H J Searle & Son expanded again, taking over the newly-vacated premises to create a triple shopfront across numbers 83–87. Although it gave up number 87 in the 1940s, it remained here at 83–85 until the mid-1960s.[26]

1960s–1970s: Alexander Sloan & Co

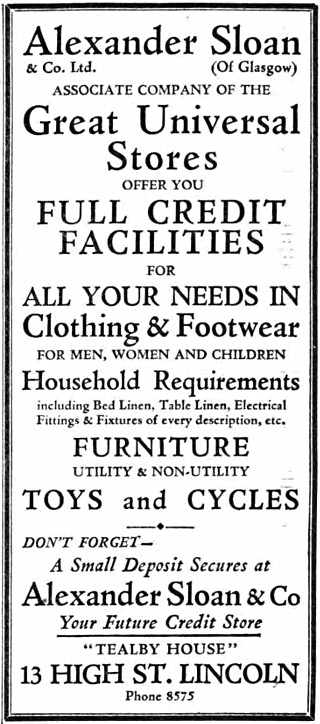

Next to arrive at the double property was another furniture firm; Alexander Sloan & Co, in place by late 1968 and remaining for the next decade.[27]

Originally founded around the turn of the century as a drapers in Glasgow, by the late 1930s the company had grown to 25 branches across Scotland and employed over 1000 people. It was then acquired by a larger company, Great Universal Stores (G U S), though continued to trade under its existing name.[28]

By the time it opened on London Road, it had branches all over the UK, including three in Glasgow, one in Wolverhampton, one in Cardiff, and at least five in Greater London. It dealt not only in furniture, but also in clothing, electrical goods such as radios, and DIY supplies including wallpaper and paints.[29]

1980s: General Guarantee Corporation

By early 1979, Alexander Sloan had been replaced by another company in the G U S group: General Guarantee Corporation. With a head office in Thornton Heath and several other branches throughout the country, this firm advertised “the most competitive terms in all aspects of Finance within the Motor Industry”, covering “hire purchase[,] personal loans[,] stocking facilities[,] bridging finance[, and] industrial building and development”.

It’s unclear whether General Guarantee used its London Road premises to interact with its customers or simply as offices. Although it certainly had a sign across the ground floor frontage by the mid-1980s, this could have been in order to comply with the council planning department’s stipulation that it would only be allowed to use the ground floor as storage space on the condition that a “window display shall be provided and maintained”. In any case, it remained here until around 1990.[30]

1990s–2000s: Migros Supermarket, Home Essentials, and M C Food

The era of finance and furniture at 83–85 London Road had now come to an end, and several years of vacancy followed. Finally, around 1997, the scene was set for the present day with the arrival of Migros, a Turkish and Greek supermarket which lasted until around late 1999.[31] The next occupant was a household goods shop called Home Essentials, in place from around mid-late 2000 to around 2002–2003, but by May 2004 the Turkish and Greek groceries were back again, this time with the addition of Bosnian, Albanian, and West Indian options, and under the name of M C Food. This remained until at least July 2007.[32]

2008–present: Beydağı Food Centre

By mid-2008, M C Food had become Beydağı Food Centre, which remains there today.[33] Named after the Turkish district of Beydağ, it advertises Turkish, Greek, English, and Polish products, and has an in-house butcher and bakery. The fruit and vegetable selection is less extensive than that at the Turkish Food Centre a few doors down, but still includes several types of fresh herbs, and occasionally more unusual ingredients such as fresh dates.

Soft drinks on offer include sour cherry juice and peach nectar, and interesting imported alcoholic drinks are available too. One aisle is dedicated to dried fruits, nuts, and roasted grains, including mulberries, sultanas, apricots, several types of raisin, chilli cashews, and roasted corn.

For me, though, the big draw is the bakery. Soft, fluffy Turkish bread is baked fresh on the premises throughout the day, and unlike most Turkish supermarkets they actually sell a brown version as well as white. Their borek have also proved very popular among the many people I’ve served them to.

Thanks to: Paulo/Drumaboy; pellethpoet; SilverWood Books and Royal London; the Planning Technical Support Team at Croydon Council; the staff, volunteers, and patrons at the Museum of Croydon; and my beta-reader Alice. Census data and some phone books consulted via Ancestry.co.uk. Several book sources consulted at the British Library. Monetary conversions performed using the Bank of England inflation calculator (prices < £100 given to the nearest penny, prices from £100 to < £100,000 to the nearest pound, prices from £100,000 to < £1 million to the nearest £1,000, prices from £1 million to < £100 million to the nearest £100,000, prices ≥ £100 million to the nearest million).

Footnotes and references

- See my article on number 79 for evidence on construction date and owner of house.

- The Tithe Award is the only place I’ve seen mention of J Lewland, so I know nothing else about them. For more information on the Tithe Award, see footnote 4 in my article on 31 London Road.

Gray’s 1851 directory lists Henry Lowman Taylor, “gentleman”. The 1851 census entry for the property is very faint, but the head of household is plausibly Henry L Taylor, age 43, “[something, plausibly Iron] Merchant”, born in Devon, and the other household members are his 41-year-old Hackney-born wife (name obscure but starts with “E” and is plausibly “Eliza”), his sister-in-law (Mary M[something]), and two female servants (possibly Ann Rogers and Sophie Mills).

The two Taylors in the 1851 census are a good match for the Henry L Taylor and Eliza Taylor living at “The Oatlands”, Anerley, in the 1871 census, and the latter are a good match for the Henry Lowman Taylor who died at Oatlands, Anerley, on 7 July 1883, and his surviving widow Eliza (see the GOV.UK “Find A Will” search). An announcement on page 4 of the 12 July 1883 Western Times reports the death of “Mr. Henry Lowman Taylor, the senior member of the Corporation of London, and its representative at the Metropolitan Board of Works”, who had “entered the Common Council as far back as 1843” and was for “many years” the “Chairman of the Markets Improvement Committee” (viewed via the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription.

A notice on page 4242 of the 28 August 1883 London Gazette gives the address of “Queen-street, Cheapside, in the City of London” as well as Oatlands in Anerley (and also mentions several other details making it clear this is the same person). An earlier notice on page 1694 of the 29 June 1841 London Gazette confirms that he was already on Queen Street at the time he was living in Croydon.

- See The Letters of Charles Dickens, Pilgrim Edition, Volume 6, p129 (viewed online at Google Books). According to the preface of that book, W H Wills was the sub-editor and business manager of Dickens’ weekly periodical, Household Words.

- Gray’s 1853 directory lists William John Wilson in place of Henry Lowman Taylor. The Taylors seem to have moved out of the area entirely, as Henry is absent from the alphabetical lists of notable residents in this directory; both the list of Croydon residents and those living in “Norwood, Woodside, Shirley, and Coomb [sic] (in Croydon Parish)”. Information on Henry’s later positions is taken from the 1883 London Gazette notice and the 1883 Western Times report cited in the previous footnote.

- William is listed in Gray’s 1853, Gray & Warren’s 1855, and Gray & Warren’s 1859 directories, as well as the October 1858 Poor Rate Book. The 1861 census instead lists John Pace and family.

- John and Henry Pace are listed here in Gray & Warren’s 1861–62 directory, which also gives Henry’s qualifications and profession as “L.L.B., Barrister-at-Law (at 23 Old Square, Lincoln’s Inn, London)”. All four family members are listed in the 1861 census, at which point John was 52, Anna Maria was 46, Henry (as “Harry”) was 27, and Amelia Charlotte was 17. This census also gives John’s profession as “Merchant” and Henry’s as “Barrister”.

The Poor Rate Books list [name beginning with J] Pace in November 1862, [unreadable initial] Trieb in June 1864 and December 1864, [name beginning with J] Trieb in July 1865, Jno [short for “John”] Trieb in November 1865, John [sic] Trieb in June 1866 and October 1866, and Leo Kerrel in December 1873. Simpson’s 1864 directory lists J Trieb, private resident. Warren’s 1865–66 directory lists — Treb [sic], esq. Warren’s 1869 directory lists Jean Trieb, merchant. The 1871 census lists Jean Trieb (aged 38, “Com agent in Foreign Goods”, born in Germany but a “naturalised British Subject”), his wife Emilie (aged 22, born in France but likewise a “naturalised British Subject”), his son Jean (aged 10 months), his daughter Catherine (aged 9), his father-in-law Maximilian [unreadable surname beginning with “P” and ending with “ll”] (aged 58, retired, born in Germany), a housemaid, and a cook.

The previous census (in 1861) lists Jean Trieb (as “Jean Tribe”) as a 28-year-old boarder at a house in Islington; he is unmarried and still a “Foreign Subject” at this point, though already a “Commercial Traveller” in “Fancy Goods”. According to Church of England parish registers available at Ancestry.co.uk (Guildhall, St Giles Cripplegate, Marriages, 1860–1863, P69/GIS/A/01/Ms 6422/11), a 30-year-old merchant and batchelor named Jean Trieb, living in Pimlico, married 36-year-old Elizabeth Bradshaw at St Giles Without Cripplegate Parish Church on 25 December 1861; despite the slight discrepancy in age, Jean’s unusual name and matching profession suggests that this was almost certainly the same person. Again according to parish registers at Ancestry.co.uk (Call Number: DW/T/0533), 39-year-old Elizabeth Trieb (by then resident in Peckham) was buried in All Saints’ Cemetery, Nunhead, on 19 March 1864.

The December 1873 Poor Rate Book lists Leo Kerrel in the place of Jean Trieb, and the 1881 census places Jean, Emilie, and their 10-year-old son on Angell Road in Lambeth. The son’s name is Alfred; this could be the same person as the 9-month-old Jean in the 1871 census, as the latter’s middle initials are given as “R A” and it’s possible he chose to go by a middle name. However, the 1871 census was taken on the night of 2/3 April and the 1881 census on the night of 3/4 April, so it’s also possible, if perhaps unlikely, that Emilie became pregnant again very quickly after Jean R A’s birth, and gave birth to Alfred on 3 April 1871, thus allowing him to be absent from the 1871 census but 10 years old in the 1881 census.

Do note that I have made a few assumptions in the story related here, including that Jean and Elizabeth were still together at the time of Elizabeth’s death.

- Leo Kerrel is listed in the December 1873 Poor Rate Book; it should however be noted that I’m not entirely sure I’ve read his surname right, as these books were handwritten. Mrs Redding appears in Ward’s 1874, 1876, and 1878 directories, as well as Wilkins’ 1876–7 (as “Mrs Reddin”), Worth’s 1878, and Atwood’s 1878 (as “Mrs Redden”) directories. Ward’s 1880 directory lists the property as unoccupied. John English appears in the 1881 census; Purnell’s 1882 directory; and Ward’s 1882, 1884, and 1885 directories. Information about John’s household is taken from the 1881 census.

- Albert Banister appears in Ward’s directories from 1886 to 1896 inclusive, though the spelling of his surname varies from “Banster” in 1886 to “Banister” in 1887–1892 to “Bannister” from 1893 onwards. I have chosen “Banister” in the text, as this is the spelling used in the census. Information about Albert’s household is taken from the 1891 census (as Albert is listed as head of the household, Thirza is explicitly listed as his mother rather than just his father’s wife). Ward’s 1897 directory lists the property as unoccupied. See my article on number 79 for more on the demoliton.

- Ward’s directories show number 83 as under construction in 1898, unoccupied in 1899, occupied by the Original Scotch Stores Company in 1900 and 1901, and occupied by William Thomas Jewell from 1902; and number 85 as under construction in 1898, unoccupied in 1899 and 1900, occupied by T Whillier in 1901, and occupied by St Paul’s Printing Works in 1902. Note that the information for these directories was generally up-to-date as of late November or early December of the preceding year.

- Ward’s directories list William Thos. [Thomas] Jewell, umbrella maker, at 59 London Road (later renumbered to 83) in 1902, 1903, and 1904. A notice on page 1306 of the 29 November 1904 Edinburgh Gazette, under the heading “Bankrupts from the London Gazette” and sub-heading “Receiving Orders”, concerns “William Thomas Jewell, 60 Fairholme Road, Croydon, lately residing and carrying on business at 59 London Road, West Croydon, collector for a trading-stamp company.” The 1901 census places William Jewell, a 31-year-old “Manager & Umbrella Maker”, at 2 Clarendon Road along with 33-year-old Elizabeth, 5-year-old Harold, and 1-year-old Marion. The 1911 census places the family at 33 Southbridge Road in South Croydon; William is now a “Tram Car Washer” working for the county council, and the family also has a boarder, 79-year-old Annie Fossey.

- The 1901 census lists 64-year-old widow Elizabeth Bergman, her unmarried daughters Beatrice (29) and Frances (22), and two visitors, Elizabeth Sharp (30) and Kate Allcorn (24). Elizabeth is living on “Private means”, Beatrice’s profession (if any) remains unspecified, and Frances is a photographer’s assistant. Ward’s 1902 directory lists St Paul’s Printing Works along with “Mrs Bergman”, while the 1903 edition has the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society and a different resident (Mrs Waters).

Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society Centenary Celebration 1843–1943, p1. Quotations also given on that page, and stated as being taken from the first half-yearly report of the Society, covering 3 March to 3 September 1843. The same page states that the first recorded meeting of the Society was that of “an entirely anonymous Sub-Committee” on 8 March 1843 at 37 Blake Street, Liverpool, “the residence of the President”. Viewed at the British Library (shelfmark: General Reference Collection X.520/8995).

I should add that late in the process of researching this article, I found another source of information on Liverpool Victoria that I was previously unaware of: Ian Saddler, A Mission in Life (The History of Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society) (Liverpool Victoria Group, 1997). This is not unlike Centenary Celebration, but includes many images of documents and copies of photographs not included in the former, and of course is able to continue the story beyond 1943.

- Thomas Laqueur (1983), “Bodies, Death, and Pauper Funerals”, Representations 1, pp 109–131 (viewed online via JSTOR; requires account). Quotations are from page 109; in the latter case, he is quoting Robert Roberts in The Classic Slum (1971, Penguin). Regarding common graves, Laqueur states that “Prior to the sanitary regulations of the late 1840s, private cemeteries could sell to the poor as many places in a common grave as the depth of the shaft would allow; paupers paid for on contract by the parish or Poor Law Union mingled helter skelter with the non-pauper poor who in nineteenth-century England had to buy their final resting place. Three coffins wide, twelve deep, they were stacked.” (p116).

- Centenary Celebration, pp3–4. The quotation is presumably the opinion of the author(s) of the book. The Cork connection might be explained by the fact that “[the] names of the earliest members of the Executive, both the Honorary Committee and the Active Committee, show that gentlemen of Irish origin took a prominent part and interest in the Society’s work (Centenary Celebration, p2).

- Centenary Celebration states on p5 that as of 1863 “the Society’s operations had penetrated to Scotland, Ireland and Wales, and in England as far north as Newcastle and as far west as Plymouth with outposts in London, but otherwise the western, south-western and southern counties had not been explored.”

- Centenary Celebration, pp11–12.

- Centenary Celebration states that “at a Special General Meeting in August, 1922 [it] was announced that a site for the new Chief Office had been purchased in Southampton Row, London, upon which it was hoped to build within two years the first section of a structure which would add ‘to the dignity and beauty of the Metropolis.’” (p25); that on 3 June 1926 the new offices were “formally opened by the Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Pryke, even though the northern section, covering about one-third of the site, was very far from complete and the rest of the site was awaiting development” (pp29–30); and that “In August, 1932, Victoria House had been completed and was formally opened in ceremony by the Chairman, Mr. S. H. Payne, who announced that the building contained 125 miles of electric wiring, 5,000 tons of steel framework, 5¼ million bricks and had provided 642 weeks’ work for an average of 300 men during a period of very acute depression in the building industry.” (p35). The caption to Worthing Wanderer’s photo of the building contains more information, though none of it is sourced. (Worthing Wanderer states that the formal opening was on 23 June 1926, which slightly contradicts Centenary Celebration’s claim of 3 June; I don’t know which is correct.)

- Ward’s directories list the Society from 1903 to 1908 inclusive.

- Ward’s directories list William Jewell at number 59 (modern 83) up to and including 1904; “Unoccupied” at 59 and 59a in 1905, 1906, and 1907; Star Rubber Stores at 59 and Henry Besley, watchmaker, at 59a in 1908; and “Unoccupied” at 59 in 1909. Number 59a only appears from 1905 to 1908, and may have been a subdivision of the ground floor or may have indicated use of an upper floor.

- Ward’s directories list number 61 (modern 85) as unoccupied in 1909; occupied by E Seymour, picture frame maker, in 1910 and 1911; and unoccupied from 1912 to 1919 inclusive.

Murray Ross, Royal London: The First 150 Years (SilverWood Books, 2011). The quotation is on page 34, and noted as being the words of Ernest Hayes, chairman and joint managing director of Royal London, while speculating on the reasons behind the Society’s formation in a speech at the Royal London centenary banquet on 2 February 1961; the remaining reasons are Murray’s own speculation. The ages of Joseph and Henry in 1861 are given on page 20 as 24 and 22 respectively, and William’s date of birth is given on page 38 as 24 September 1838. The date of the Society’s certification is given on page 40.

Another history of Royal London also exists: We The Undersigned... by W Gore Allen, published in 1961. In the introduction to Royal London: The First 150 Years (page 11), Murray Ross describes this as “an attractively presented book, written in an engaging style” which nevertheless “comes over as a history of Britain into which some Royal London events had been skilfully slotted.” Following a brief flick through it, I’d say this seems a reasonable assessment, but I mention the book here anyway for completeness.

Finally, Royal Liver itself had a presence on London Road in the 1960s–1970s, first at number 74 and then at number 21.

- Royal London: The First 150 Years, page 111, gives the date of the formal conversion as 31 July 1908; the remainder of this chapter (Chapter 5; pp 93–113) discusses the views of the proponents and opponents of said conversion. Joseph was not to see this vindication of his earlier desire to see Royal Liver convert to a company, as he died just over a decade after the founding of Royal London, on 26 December 1874.

- Ward’s directories list the “Royal London Mutual Insur Soc” at 83 London Road from 1910 to 1930 inclusive (as 59 London Road before 1928).

- As noted in an earlier footnote, Ward’s directories list number 61 (modern 85) as unoccupied from 1912 to 1919 inclusive. H J Searle & Son is listed at number 63 (modern 87) from 1908 onwards, at 61–63 (modern 85–87) from 1920 onwards, and 83–87 (the modern numbering having been adopted in 1927) from 1932 onwards. I’ll discuss the company at greater length in my article on number 87, where I’ll also provide evidence for how long it stayed at its various London Road addresses.

- Alexander Sloan & Co is listed at 83 London Road in Croydon phone books from September 1968 to July 1977 inclusive.

An article on page 7 of the 4 June 1938 Dundee Courier describes Alexander Sloan & Co as a “drapery firm with warehouses in Glasgow and 25 branches throughout Scotland” and “one of Glasgow’s oldest credit drapery houses” employing “over 1000 people” (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). The term “credit drapery” means that the goods were paid for in weekly installments; according to Stephen Aris’ The Jews In Business, “The usual system was for companies like Alexander Sloan [...] to employ tallymen, familiar figures in any working-class district, who travelled round delivering the goods and at the same time collecting the weekly instalments from the householders. It was an early and more personal form of hire purchase.” (Chapter 6, p113; Penguin, 1973).

Alexander Sloan’s acquisition by G U S is described in a report on the latter’s 1938 Ordinary General Meeting, published on page 7 of the 13 June 1938 Lincolnshire Echo: “For some time they had been investigating with a view to purchasing a 40-year-old established and progressive business of a kindred nature and which they were satisfied would fit admirably into the structure of their organisation. The profits of the business had been substantial, and during the last two years had averaged £120,000. They had now completed negotiations for the acquisition of this undertaking — Alexander, [sic] Sloan and Company, Ltd., of Glasgow — which they felt assured should prove a valuable asset.” (viewed online at the British Newspaper Archive; requires subscription). The same report notes that Great Universal Stores’ own annual profit over the past year had been £408,714; a little over three times as high as that of Alexander Sloan & Co.

Further information about G U S and its acquisition of Alexander Sloan can be found in Chapter 6 of The Jews In Business.

- The February 1968 London phone book lists Alexander Sloan & Co Ltd, “Wrehomen” [warehousemen] at 10 & 15 Cleveland Way E1, 2 Kilburn Bridge NW6, 89 Lambeth Walk SE11, and 151 Lewisham Way SE14 (“Radio Serv [servicing?] Dept”). The April 1968 Outer London: North East Surrey phone book lists Alexander Sloan & Co Ltd, “Credit Drprs” [drapers] at 246 Sutton High Street (as well as “Offs” [offices?] at 83 London Road). The June 1968 Glasgow phone book lists Alexander Sloan & Co Ltd, “Gen Wrehomen” [general warehousemen] at 45 Bridge Street, 22 New Street, and 30 Carlton Court (“Radio Serv Dept”). The September 1968 West Midlands (Northern) phone books lists “Alex” Sloan & Co, “Wrehomen” at 27 Pipers Row, Wolverhampton. The March 1968 Cardiff & South East Wales phone book lists Alexander Sloan Ltd at 45 Salisbury Road, Cardiff (“Radio Serv Dept”). Some photos exist of the Wolverhampton branch: in the late 1930s (see also Colourful Characters of Pipers Row) and in 1980. Phone book entries for the Croydon branch include descriptions such as “Credit Drprs [drapers]” and “Wrehomen [warehousemen]”, while the 1974 Goad plan describes it as a “furn [furniture] wallp [wallpaper] & paint whse [probably either ‘warehouse’ or ‘wholesale’]”.

General Guarantee Corporation Ltd is listed at 83 London Road in Croydon phone books from January 1979 to 1990 inclusive (as “Indust Bnkrs [industrial bankers] (Branch Office)”; note that phone books generally only showed a single street number even for companies with a range of addresses) and at 83–85 London Road in Goad plans from 1983 to March 1990 inclusive (as “offices”; note that I don’t have access to Goad plans before 1983, aside from the 1974 one). It also appears at 83–85 in Brian Gittings’ 1980 survey of central Croydon retail (as “General Gaurentee [sic] Corporation”), and a photograph included in the records of a mid-1980s planning application relating to number 81 next door (ref 85-448-A) shows a sign reading “General Guarantee” on the ground-level double property at numbers 83–85. The planning application in which the company was instructed to provide a window display was granted on 16 May 1978 for “Change of use of shop to storage in connection with the use of the upper floors as offices” (ref 78/20/53).

The June 1991 Goad plan shows 83–85 as vacant, and the February 1992 Croydon phone book lists only a single address for General Guarantee Corporation; Ambassador House on Brigstock Road.

Other details of the company are taken from an advert reproduced in Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History. No information on the provenance of this advert is given, but it’s captioned “October 1973”. The advert contains the quotations given above, as well as the statement that it is “A G.U.S. Group Company”, the address of Ambassador House, Brigstock Road, Thornton Heath, and the claim of “branches throughout the country”. Croydon phone books (1982 to 1992 at least) confirm that Ambassador House was the company’s head office. Ambassador House itself is an office block just opposite Thornton Heath Station; according to the caption of Stephen Richards’ photo on Geograph, it was built in the 1970s, which certainly looks plausible to me, and thus suggests that it was newly built when General Guarantee Corporation moved in.

- Goad plans list the property as vacant from June 1991 to May 1997 inclusive. Migros appears in the January 1998 and July 1999 phone books (as “Migros Supermarket”), the June 1998 and September 1999 Goad plans (as “M Migro’s”), and the second edition of Shop ’Til You Drop (likely published around 2002). The only one of these sources which states the type of groceries it sold is Shop ’Til You Drop.

- Home Essentials appears in the January 2001 Croydon phone book and the June 2001 and May 2002 Goad plans. M C Food appears in Goad plans from May 2004 to July 2007 inclusive. A photograph dated 29 September 2005, included in a planning application relating to numbers 73–77 (ref 05/674/P), shows the frontage of M C Food with a sign above reading “English / Turkish / Greek / Grocery / Bakery / Off Licence” canopies reading “Bosnian & Albanian Foods” and “English — Turkish — Greek — West Indian”, and what look like displays of vegetables on the pavement.

- Google Street View imagery from July 2008 shows Beydağı Food Centre looking pretty much identical to the way it looks today, except with a slightly different canopy and some fading on the frontage sign. All other information about this shop is from personal observation.